Tale of “two-legged people”

by Maria Trefely-Deutch,

The Sunday Telegraph, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia,

23rd November 1992.

At the dawn of this so-called New Age, many people question the basic tenets of our materialistic society; some feel a spiritual vacuum and, as our physical environment becomes increasingly fragile, are beginning to question our relationship with it. There is an awareness we have lost something, that we are no longer in tune with the planet. The few indigenous peoples who still carry the wisdom of their ancestors are rapidly dying out or being assimilated in the dominant culture.

Andrew Hogarth, a Scot living in Australia, has long recognised the gifts of the indigenous peoples of North America, and has spent years studying them. He brings us a piece of marvellous oral history in the story of Jack Little. Jack, who died in 1985, leaves as his legacy his story which mirrors that of his people. He was from a branch of a nation we know of as Sioux. He explains that the word “Sioux” is actually French and has nothing to do with what he is.

He describes himself as Lakota, meaning “The People.” According to Jack “it is only a word that distinguishes the two-legged people from the four-legged and the winged people who live here with us, and yet if I tell a man from any tribe here that I am Lakota, he knows where I am from.

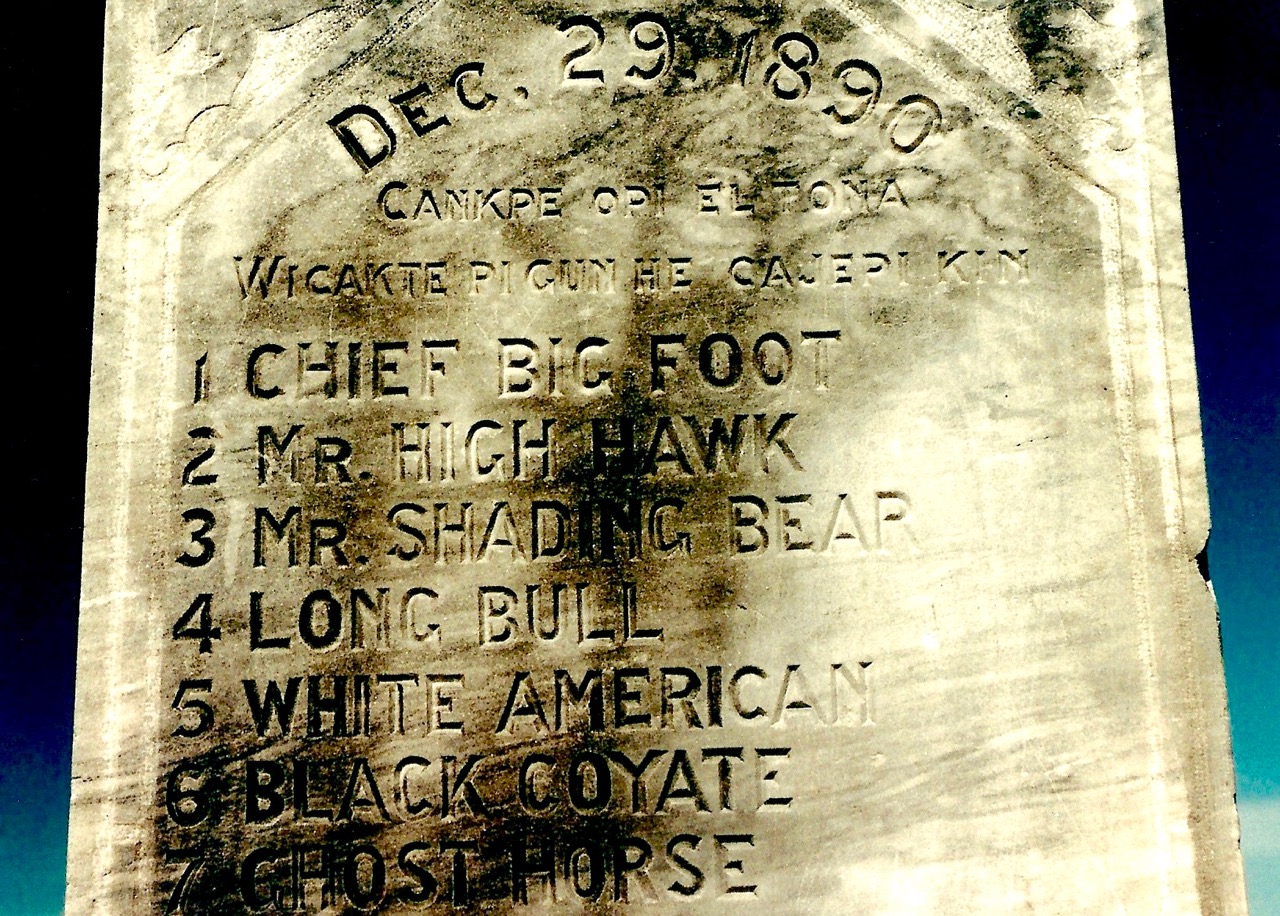

In a way Jack serves as a link between the time the Sioux were a free nation and the state of cultural suppression and near extinction in which they find themselves. Jack was actually born in a tepee and as a child knew survivors of the resounding defeat at Wounded Knee Creek in 1890. Until six he lived the life of his ancestors. Then came the rude shock when he was sent to mission school. These were years of turmoil when Jack was told that the “old ways” were no good.

After leaving school Jack was to see a lot of the White Man’s world. He travelled the country playing basketball. Later he drifted from job to job, increasingly aware of the spiritual bankruptcy of the White Man’s world. Like many of his people, he succumbed to alcohol in a frenzy of despair, hurt, bewilderment and fear. He eventually married a white women he met in a detox unit and they became alcoholic counsellors to the Lakota.

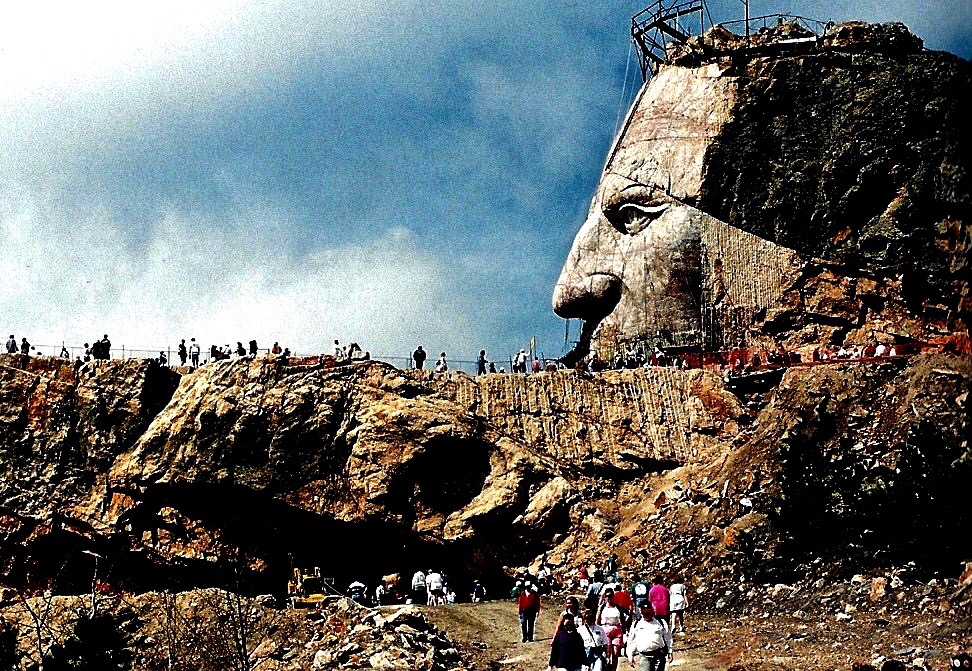

By the time of his death, Jack Little had in a sense come home, as he was working as a guide and lecturer at the Indian Museum at Crazy Horse Mountain in South Dakota. Although at peace with himself, Jack Little’s parting message is pessimistic: The white man in his greed has gone too far and is on a path to destruction that will take all other people and forms of life with him. But on a cryptic note he points out that, like the coyote, the Indian is hard to exterminate.

Andrew working at News Limited in Sydney Australia 1992

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.