Scotsman’s book tells story of Teton Sioux

by Debra Bossman

The Rapid City Journal, Rapid City, South Dakota, USA, 15th July 1985.

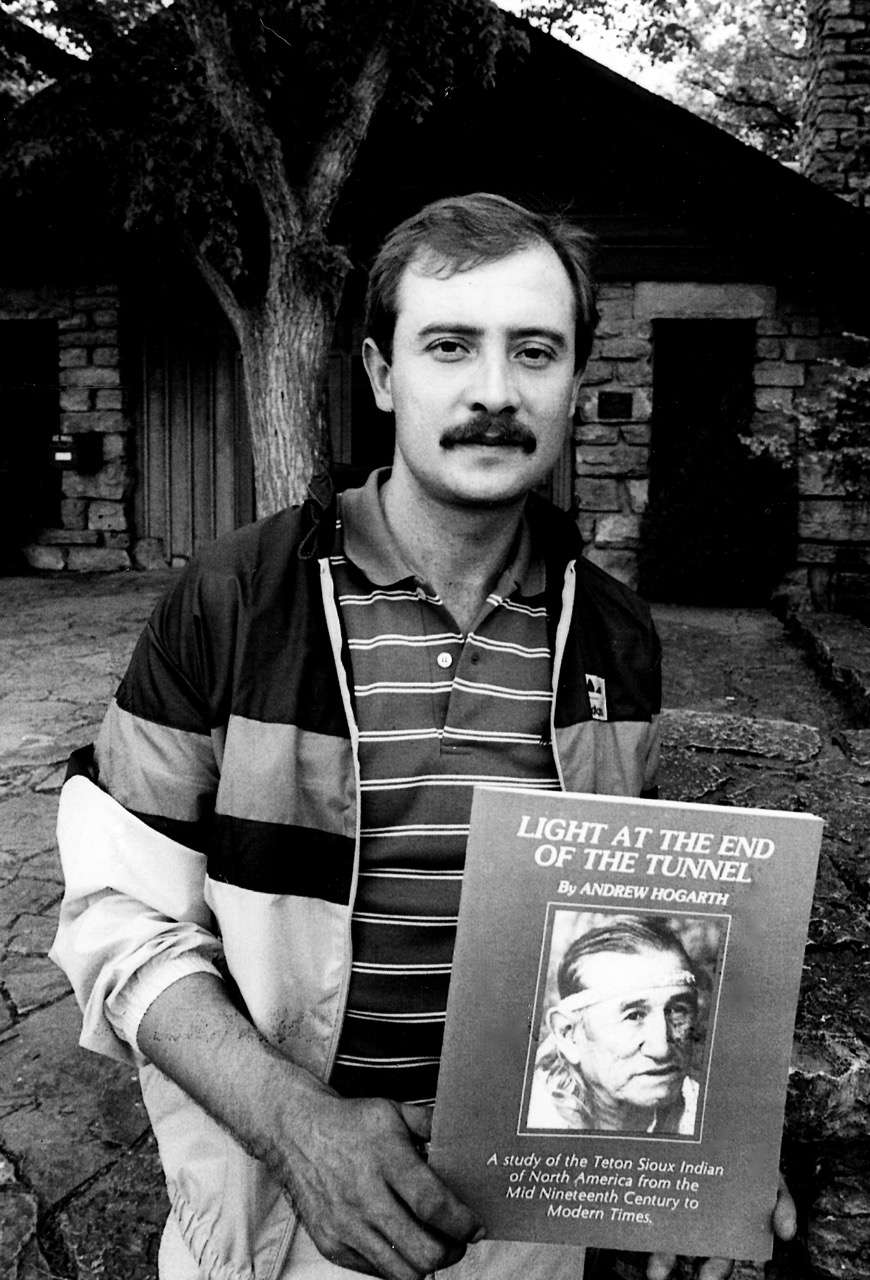

Andrew Hogarth author of “Light at the End of the Tunnel,” didn’t believe American Indians could be as they were portrayed in B-grade westerns. So he set out to find their true identity and write about them.

The native of Scotland, who is visiting in the Black Hills this summer, has travelled more than 16,500 miles researching and promoting his book about the Teton Sioux. “Light at the End of the Tunnel” has now sold more than 2,500 copies.

“Hollywood made them (American Indians) unbelievable,” Hogarth said in a distinct Scottish brogue. “There was always an endless supply of Indians coming over the horizon in the movies and John Wayne never ran out of bullets.”

Hogarth first became interested in the Sioux after reading several books he purchased while in New York. His interest ultimately brought him to South Dakota in 1982 on his third trip to the United States of America.

On that trip Hogarth visited Crazy Horse Mountain and met a man who would complete the focus of his book. “Jack and Shirley Little contributed enormously to my understanding of the Sioux, both past and present,” Hogarth says. “Jack really leaves an impression on you. He speaks for himself about how he is feeling.”

Before publishing his book, Hogarth wrote several articles – “A Culture Died at Wounded Knee,” “In Search of An Identity” and “The Little Bighorn 1876” – for an ethnic publication in Sydney, Australia.

He began work on the book in December 1984 during a Christmas holiday. Most of its contents is researched from other publications and then combined with Little’s story.

“I created the book to simply bring to a wider range of readers a culture that respected the earth it lived on, loved and shared with its own kind,” he says. “They treated animal life with respect and were probably the last true free people to live on this planet.”

Hogarth says when Indians were forced to the reservations they not only lost their ponies and weapons, but also their freedom and precious way of life. “I see a people (now) who have been stripped of their pride. They are angry and frustrated because of it,” Hogarth explained. ‘I have great respect for the Indian people.”

Hogarth was impressed by the individuality of American Indians. “You could tell right away what kind of person each warrior was by the markings on him and his horse. We were often led to believe they were always fighting, but in reality very few Indians were killed in battle.

Many of the American Indian ways of life parallel the struggles of their ancestors, according to Hogarth. “The book examines the trials endured by the Teton Sioux nation in their fight to halt the spread of the white man’s civilisation. It also documents the rise of Sioux Chiefs Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, who are now finally beginning to receive just acknowledgment of leaders of their people.”

Hogarth notes that many Sioux have succeeded in white society, but the majority find integration difficult. “I didn’t see a lot of prejudice of Indians, but (some0 white people see them as drunken Indians and not as a product of what society has done to them.”

Little, a full-blooded Oglala-Brule-Sioux, restored Hogarth’s faith in the strength and pride of the American Indian. It is Little’s face that graces the cover of “Light at the End of the Tunnel”

“I doubt very much if the Lakota will ever forgive being forced into the position of being in a minority in our own land,” Little explains in his section of the book, which explains aspects of Sioux religion and culture and relates his personal experiences as a Sioux in an alien culture.

‘The white society can force its education, its religion and its ways on us all they want to, but we will always be Lakota, and think and act Lakota,” writes Little. ‘Our very creation is in this land and the lessons learned by our ancient ancestors of how to live peacefully with this land have been born into us. If a man has any Indian blood at all, he has some thought and feelings that are alien to the white man’s world, but natural to this land.”

The 35-year-old Hogarth says this is his first – and last – book. He plans to revise portions of it for a second printing later this year and distribute the books in South Dakota and Australia.

He’s had some difficulty cutting through “bureaucratic red-tape” in marketing his book at National Park locations, but says he will continue to promote his work in a quest to tell the Indians’ story.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.