National Library of Australia Card Number and ISBN 0-646-09648-6.

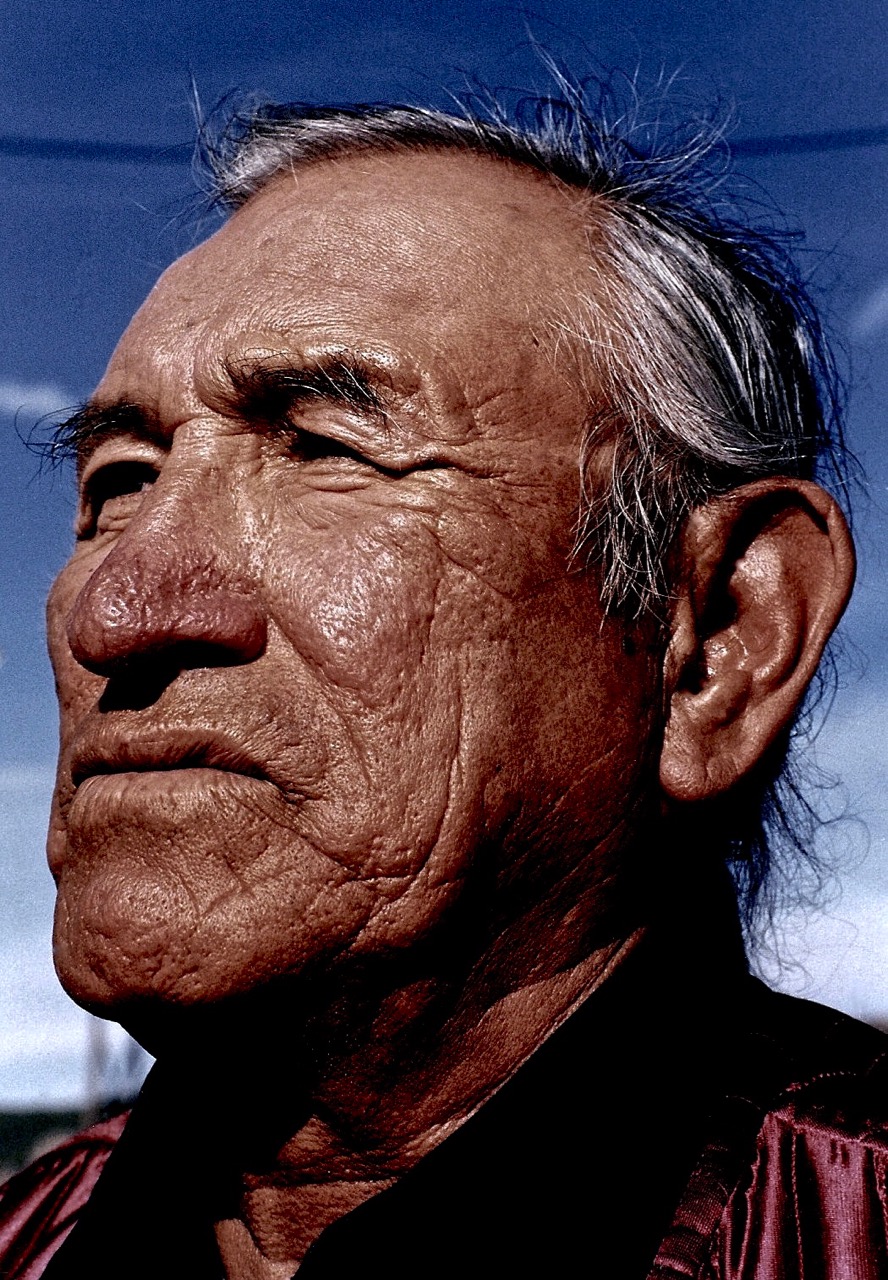

In October, 1982 I met Jack Little and his wife Shirley while spending time in the Black Hills of South Dakota. The Black Hills are considered the sacred heart of the Sioux Nation. Jack Little worked as a guide-lecturer at the Indian Museum at Crazy Horse Mountain. Crazy Horse Mountain is a carving in progress of Oglala Sioux War Chief Crazy Horse. The life of Crazy Horse is symbolic of the Sioux Nation’s fight for freedom and equality. In his capacity as guide/lecturer Jack spoke to a great many people about the Sioux way of life. He was eloquent, direct, informative and, as you read his story, you will realise his message is prophetic. Over a number of years as our friendship developed Jack agreed to record his life story with the help of his wife Shirley. His story is the personal side, the unconsidered information not included in the history books.

At the year’s end of 1890 the United States government announced that an Indian frontier no longer existed. From the arrival of Columbus on the eastern seaboard in 1492 until this announcement in 1890 approximately six million Native Americans died. Death resulted from diseases such as cholera and smallpox, massacres by civilians and soldiers, relocation from ancestral homelands to remote, isolated and desolate areas of the North American continent and the dissemination of their culture.

For more than three decades from one of the earliest incidents in 1854, through to the victory over Custer’s Seventh Cavalry at the Little Bighorn in 1876 and finally defeat at Wounded Knee Creek in 1890 the Sioux Nation of the Great Plains region resisted the intrusion of the white man into their lands and way of life. In the years between 1877 to 1890 Sioux leaders that opposed the white man’s ways were systematically murdered, American Horse (1876), Lame Deer (1877), Crazy Horse (1877), Spotted Tail (1881), Sitting Bull (1890) and Big Foot (1890).

The nomadic Sioux were forced to settle on reservations, the buffalo herds were slaughtered to near extinction and families divided by law, loyalties and foreign religions. The Sioux, as with other Native American tribes, were forced to become unwilling wards of the State, in effect, prisoners of a foreign power. A resourceful and self-sufficient people were reduced to a position of dependence on an uncompassionate master.

The massacre of two hundred and ninety-eight Minniconjou and Hunkpapa Sioux at Wounded Knee Creek in late December, 1890 essentially broke the sacred hoop of the Sioux. Two-thirds of the Sioux killed were women and children, their bodies were found strewn and scattered over an area of more than a mile from the site of the initial engagement.

At the beginning of 1890 an estimated one hundred thousand Native Americans survived on the North American continent there were thirty-thousand Sioux. Still not content with the destruction fostered by the white man’s greed the United States government actively pursued the systematic genocide of those remaining Native Americans by outlawing sacred ceremonies, language and the division and separation of the family unit which forms the basis of Sioux culture. On Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota one hundred and thirty-six church groups were established with land grants. Their target was a mere ten thousand Sioux. One church for every seventy-three Sioux!

In the eight decades from 1890 to 1970 as the United States of America grew in world stature and white Americans led an “ideal” life the Native American population was conveniently forgotten, left to struggle with a lifestyle not of its own choosing. Poverty and alcoholism became the silent killers. In 1924 Native Americans were granted the right to vote, in 1939 the freedom of religious choice and in 1946 the first Native American claims commission was set up. However, schools which actively encouraged the separation of children from their families and discouraged the use of native languages continued operating until the late 1980?s.

The 1960?s and early 1970?s saw a rise in political awareness and activism across “white, black and red” America. White Americans experienced the indifference of their government and began to question the values cultivated by their institutions and the media. The emergence of the American Indian Movement in the 1970?s marked the arrival of Native America back into American consciousness and a move by Native Americans toward traditional values and identity.

The occupation of the Wounded Knee Massacre site in 1973 for seventy-one days which protested United States government policy on the reservations marked the rise of solidarity between Native Americans. In the years following the Wounded Knee occupation the Sioux have continued to work toward re-establishing their identity and traditional values. The re-emergence of traditional values and consequently self worth have contributed toward healing the wounds of their ancestors and are their hope for the future in the continued struggle for self determination and acceptance as Native Americans.

In November, 1985 Jack Little died in Rapid City, South Dakota. He was returned to Mother Earth in his Lakota birthplace at Spring Creek on the Rosebud Reservation. The release of “Lakota Spirit” is a tribute to the memory of Jack Little and the indomitable spirit of the Sioux Nation.

Andrew Hogarth, November 23, 1992.

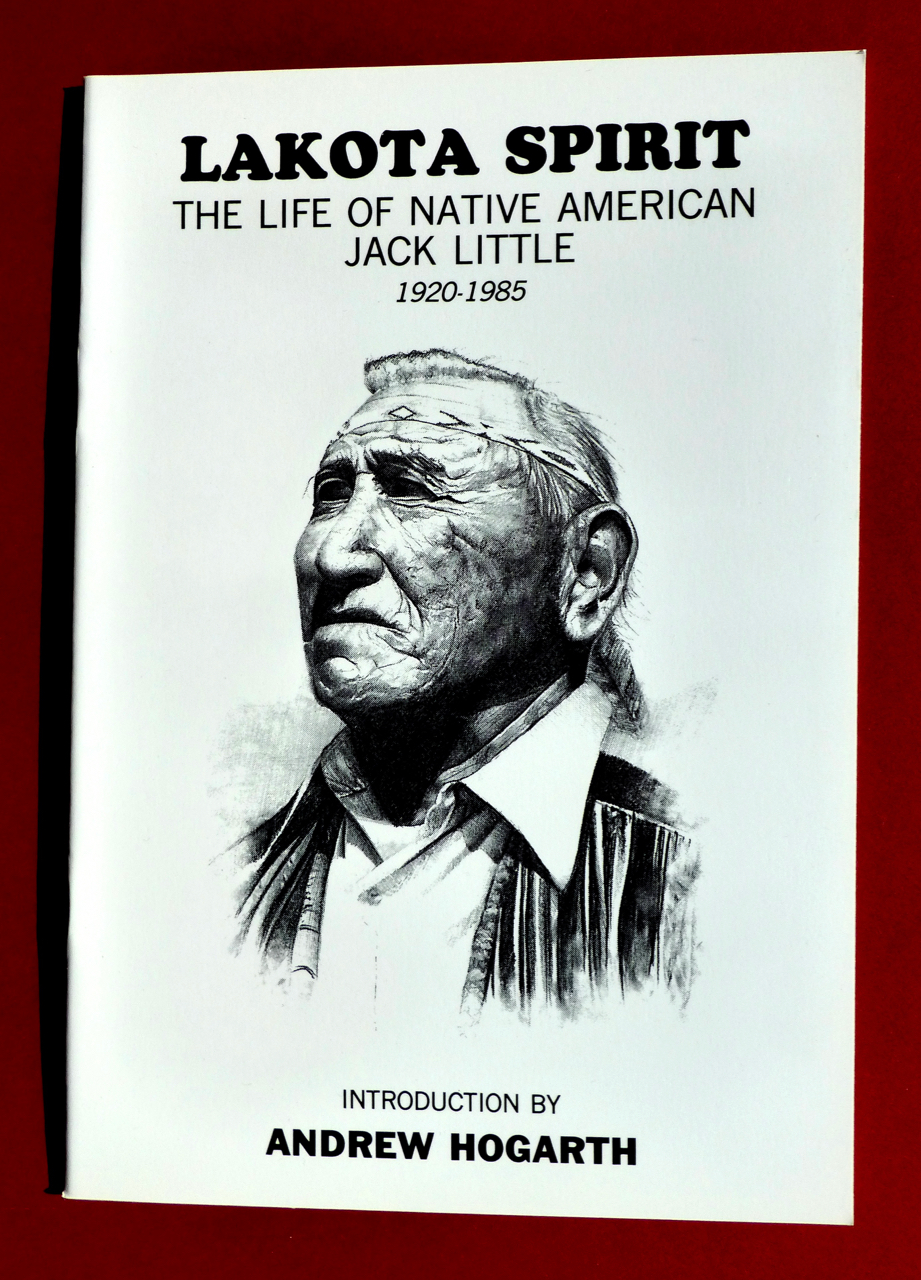

@ Copyright 1984, Jack and Shirley Little. First published Sydney, Australia 1984 by Andrew Hogarth. First reprint 1986. Second reprint 1992. All rights reserved. Art design: Andrew Hogarth. Map graphics: Andrew Hogarth Front cover and contents illustrations: Paul W. Farley. Photographs: Andrew Hogarth (unless otherwise credited). Historical photographs courtesy of the National Archives, Washington, DC. This booklet is sold subject to the condition that it is not to be reproduced either in whole or in part, stored in retrieval system or transmitted in any form without prior permission of the authors and publisher. Reprint by Permission of Shirley Brown Thunder 1992.

Chapter 1 The Reservation Years

I was born on April 18 1920 at Spring Creek on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota. I am probably one of the few Lakotal left who were actually born in a tepee. My parents were building a log cabin and were still living in their tepee when I was born. I am the oldest of five children. four boys and a girl. Today I have two brothers among the living. To say to which of the seven branches of the Sioux I belong is very difficult. There are two reservations very close together, Pine Ridge and Rosebud.

When my people were forced onto the reservations bands and even families were split. Those people on the Pine Ridge Reservation refer to themselves as Oglalas, and those on the Rosebud Reservation refer to themselves as Brules. I have many close relatives on the Pine Ridge Reservation so I really don’t know whether I am Oglala or Brule. I do know that my mother came from Chief Rain-In-The Face’s band, which was near Wanbli on the Pine Ridge Reservation. I cannot help but think that families were deliberately split to demoralise the people. Family and relatives were and are the most important consideration to my people and to split them apart would be the most effective way to demoralise them.

Today I call myself “Lakota.” I do not call myself “Sioux” or “Indian” except for clarifying purposes when I am talking to non-Indians. “Sioux” is a French word which has nothing to do with me, and the word “Indian” belongs to another nation of people. “Lakota” is what I am, and the translation of the word is simply “The People.” It is only a word that distinguishes the two-legged people from the four-legged and the winged people who live here with us, and yet if I tell a man from any tribe in this country that I am Lakota, he knows where I am from.

On the day I was born a man called Crazy Cat walked through the snowstorm to our tepee to give me my baby name, and until I was taken to the missionary school I was known as “Hohu.,,2 A person’s name was very important to my people. One’s name was thought to have a certain power, and each and every individual had his or her own name. When a child was born, he or she was given a baby name, usually by some older and respected member of the clan. Later in life, usually the early teen-age years, the person acquired his or her real name.

In the case of a boy, his name most often came to him in a dream or a vision. A medicine man helped him understand his dream or vision, and from that interpretation his name was determined. As my people were a part of nature, and considered every living thing in nature as relatives, the dreams or visions they had were most often about animals, birds, the sky, the earth, anything that was found in our natural environment. Consequently, real names of the men were often names like Black Elk or Little Elk, Two Bears or Quick Bear, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, Pretty Eagle, Little Wolf, Touch-The-Cloud, Red Cloud, Rain-In- The-Face and White Whirlwind.

Young girls sometimes had dreams or visions, but more often their names were derived from some personality trait, or something unusual they had done. Their names were such as Mountain Wolf Woman, Gentle Bird, Bird Woman, Elk Woman, Yellow Feather, Good Woman and Morning Star. A woman kept her name for life. She did not have the name of a parent when she was a child, and she did not take the name of her husband when she was married. Like the men, she was an individual with her own name.

About eight miles from where my parents lived, there lived an old man named Mahalhpaya. Although he was my granddad’s brother, in the Lakota way, I always called him Grandfather. Grandfather had lost a leg in the Wounded Knee Massacre when he was a young man, and so he had a peg leg. Although Grandfather died when I was nine years old, he has always been an influence in my life. As a small boy, I learned many things from him. Today I regret that I did not understand the importance of what he was teaching me. If I had understood then that he was giving me guidelines to live by; that he knew what I was facing in the white man’s culture, and was trying to prepare me for that, I would have listened more carefully. I do remember many of the things he told me, and it seems as I get older, more of his words come back to me.

Mahalhpaya started taking me into the sweat lodge when I was four years old, and I learned the meaning and importance of the sweat lodge, the oldest of the Lakota ceremonies. I learned to sing the songs and say the prayers. Later, I shall explain more about the sweat lodge, but for now, it is sufficient to know it was a means of the Lakota purifying himself physically, mentally and spiritually. I remember my very early childhood as a time of freedom and contentment. I had my relatives, those who loved and cared for me; I lived a free and happy life, and I spoke Lakota, which was the only language I knew existed. My paternal grandfather had a large amount of land and had many cattle and horses, and we had great times at his home. Many relatives would come and camp for maybe a week or more. Grandfather would butcher a couple of cows and there would be much to eat and much happiness. I never knew what happened to my grandfather’s land. At that time it was a part of the reservation. But, today that land is owned and farmed by white men, and is no longer a part of the reservation, so I am told.

One of my relatives, the wife of my grandfather’s brother, was also a survivor of the Wounded Knee Massacre. In the Lakota way, she was known as “Grandmother” to me. Grandmother was a young girl when she was at Wounded Knee and was a member of Big Foot’s band. She and her mother were trying to get away from the killing, and her mother was leading a horse. The soldiers killed her mother and the horse, but somehow the bullets missed her, and in the con- fusion she managed to hide herself between the bodies of her mother and the horse. She stayed there the rest of that day and all night, and sometime the next afternoon, some of my people found her as they were searching the prairie for survivors. Grandmother and Mahalhpaya did not speak often of their experiences, but I am sure that just knowing what had happened to them must have had some influence on my feelings even then.

There were other things that I accepted as not unusual when I was a child. It was not until I grew older that I began to question why these things were as they were. I can remember being taken to a Sun Dance when I was quite small. I did not question why we had to go to the Sun Dance in secret, and I was not to talk about it afterwards. I did not question why we had to go a way back in the hills for this Sun Dance, and why certain people placed themselves where they could see for several miles and tell who was approaching. It was not until I was older that I realised that, according to the United States Government, holding this Sun Dance was illegal. My people were not to practise their religion. Although the Government said this was because our religion was savage and uncivilised, the real reason was to break the spirit and unity of my people. The Sun Dance was our most important ceremony as it brought my people together once a year for spiritual renewal and unity. Somehow, some of our old medicine men managed to keep many of the old beliefs alive. This law prohibiting my people from practising their religion was in effect from 1883 until the late 1920s.

When I was six years old, after coming out of the sweat lodge one evening, Grandfather Mahalhpaya told me I was going to go to school. I had no idea what he was talking about, but I did know he thought I was facing something that was going to require a great deal of spiritual strength and fortitude. I was taken to the St. Francis Mission about six miles from where I lived. It was run by the Catholic Church and is still standing and in operation today. I arrived confused and scared and not having any idea what to expect. I had to live in a dormitory with other boys. We were not allowed to live at home because it was thought our parents would not be a good influence on us. I did not know one word of English; in fact, I had hardly ever heard it spoken, and yet we were not allowed to speak a word of our own language.

The punishment for breaking this rule was being hit, going without meals, or being literally locked up in a dark closet. I do not know who set up the rules but the Sisters carried them out. Only English could be spoken and it was three years before I could make any sense out of what was being said to me, and even when I could understand what the Sisters were saying to me, much of it didn’t make sense. Those years of struggling with the English language and an alien religion earned me many punishments which, as time went on, brought on my anger and resentments. I began to look at the white man and his religion as an enemy, or at the very least, something very bad that had to be endured.

When I arrived at the mission, I was given the name of John Baptiste Little. It was many months before I even realised that that was what I was to be called from then on. It was a great insult to me! “Cig’ala” was my father’s name, which translates to mean “Little.” They had not only given me my father’s name, but they had put some other words with it that really had no meaning. Immediately, my individuality was threatened. I interpreted this as a personal threat to the person, I was and the person I would become. They were not going to let me be myself, they were going to make me into what they wanted. Because of the pressure on my people to become “civilised.” and my years of being confined in school, I never had the opportunity to earn my own name. And so, I have gone through 64 years of my life with my father’s name, two names that have no meaning, and my baby name, but never have I had a real name with power which meant anything.

Summer vacations are the only happy times I can remember during those early school years. I could go home and forget that white man’s world for at least a few months. I could forget their rules and regulations, the complexities of their language, and their angry God that they tried to thrust on me. I could be Lakota and be free and happy. When I came home from school for the summer, my dad would bring in the horses. We were just young boys, but my father would tell us to pick out our horse for the summer. These horses had been on the range all winter and some of them had never been ridden. It was, nevertheless, up to each of us not only to catch the horse, but to gentle it, and break it to ride. Since I was the oldest, my younger brothers usually persuaded me to break their horses for them. I took many a hard spill from those horses, but I was never seriously hurt.

The horses were our transportation for the summer. There were miles of reservation land with no fences and we could go anywhere we wanted. If we were hungry, we simply stopped at some one’s house and ate, or if it was growing dark and we were too far from home, we simply stopped at someone’s house and slept. We were welcome anywhere with my people, and were never looked at with suspicion and distrust, as we had learned to expect at school. If there was a horse race going on somewhere, I always took my horse, but other times I preferred to run wherever I was going if it was not more than a few miles. And, I know of at least one time that my brother and I outran some of the other boys on horses! There was a white man who lived on the reservation and he had some cattle.

A number of us boys had found some of them behind a hill, and we proceeded to have a rodeo. We were having great fun riding those cows and half-grown calves, until a rancher came over the hill with a shotgun in his hand. The other boys scrambled for their horses, but Gus, my brother, and I didn’t have time for horses. Going as fast as our feet would carry us, we passed those boys on horses and even got cross the creek, which was a boundary line, before they did. And, not only that – Gus and I had on shoes that we were to wear to school that fall, and although Gus didn’t even stop at the creek, but ran right straight through it, shoes and all, I stopped and took mine off before crossing the creek. Afterwards, we all sat up on a hill a good safe distance away, and felt brave enough to throw rocks and yell insults at the rancher, who was a good half mile away.

We did have a few friendly white neighbours on the reservation. We played with their children, and they roamed all over the reservation just as we did. Their parents lived basically the same as ours and there was no animosity between us that I can remember. Although we spoke different languages, it did not seem to be a barrier. Our families shared with them what we had, and they did the same, and we all learned from each other. What made this possible at that time was a mutual respect for each other. All of that has changed now, though. The white society demands respect by virtue of the colour of their skin, and gives no respect in return, by virtue of the colour of our skin.

Those early days were happy days, but I can see now what the white man’s education was doing not only to me but to the rest of my people. Being told over and over again that your people were wrong and were a bad influence on you, and that your parents’ religion was sinful, eventually took its toll. A little shame crept in because your parents could not speak English well, because your grandfather only knew two words in English: “Yes” and “No,” and because he laughed heartily every time he used one of those two words because they sounded so ridiculous to him. “The Old Ways,” we were told, were not good, and we must learn to read and write English, learn to dress nicely, learn the white man’s courtesies: how to eat properly, speak properly, and act properly. And, most of all, we were to learn to worship their Christian God, not in a way that was natural to us, but as we were told. They spoke of all the good rewards that would be ours if we did all these things. If we turned out backs on our parents and elders and listened to “them,” we would really be somebody. Hurting memories and scars for life were picked up during those years of turmoil.

Chapter 2 The White Man’s World

One of the last conversations I had with Grandfather Mahalhpaya was when I was about nine years old, shortly before Grandfather died. I hated the school and the kind of life they were forcing upon me, but Grandfather told me, “Hohu, go to that white man’s school and learn everything he has to teach you. Learn it all well, even better than him. Then go out in that white man’s world and try, try very hard. But, when the time comes that you find you cannot be a white man, come back home and be Lakota.” I have never forgotten his words. It is as if he said them to me yesterday. So, I went to the white man’s school and the only good thing that came of it as far as I can see, is that I learned I was an exceptional athlete. I learned to play basketball and I was good. In high school we beat the other schools around us, including the white man’s, so many times that they didn’t want to play us any more.

After we got out of high school, four other Lakota boys and myself formed a team. We were named the “Sioux Travellers,” and travel we did! Since none of the teams around wanted to play us, we went on the road. For about six years, we played teams across the United States, all the way to the East Coast. Occasionally we were beaten, but much more often we won. We played against independent teams and college alumni teams, and won so many times that we knew we were good. We played a running game and the white boys couldn’t keep up with us.

We learned that on the ball floor, we were in better shape than they were, and that the Lakota could beat the white man at his own game. We could run a whole game and not be tired. We had to play this way and this well because we had no substitutes. I believe that running is a natural ability of the Lakota. I remember one of my grandfathers running everywhere he went. He never walked from one building to another, he always trotted. When he went to Saint Francis or Rosebud, he ran. He died when he was over seventy years old, and that very morning, he had run three miles to town. He had a heart attack while in town and some people were bringing him home in a car and he died on the way.

Travelling every ball season with the Sioux Travellers was exciting, and I thoroughly enjoyed it. We had earned the grudging respect of the white people, we were being paid to play ball, and I thought I had the world by the tail! I had it made! Although our schedule was exhausting, sometimes requiring us to leave after a game and travel all night and the next day to play another game, we were young, we were Lakota, and we could take it! We drove through any kind of weather, snow storms included; we saw cities large and small, we saw this country from one end to the other, and always there was the excitement of the next game ahead of us, Life on the reservation seemed very remote and far away.

Off seasons were spent working at various jobs. But, some time each summer, I was drawn back to the reservation: besides my family being there, it was still home. When my people were first forced onto the reservation, it was like a prison to them. But, even a prison can become home after a couple of generations. It was all familiar to me. I did not have constantly to be on guard against saying or doing something of which the white people did not approve. I was Lakota, and I thought differently and felt differently than the people I was trying to be like, and I had to be very careful. At that time though, the success on the basketball floor made up for it.

During those six years, I learned the value of money. Or, I should say, I learned the power of it and what it could buy. I have never learned to regard money as does the white man. I do not think in terms of money being a remedy for tomorrow’s problems, like a bottle of pills hoarded in case one gets sick in the future. As a Lakota, I do not worry about tomorrow. I will take care of it when it gets here. I still find it difficult to think of bills that must be paid next week or next month. If I have money today, I am inclined to give it to someone who needs it or spend it, and let tomorrow take care of itself. This is the Lakota way. We regard each new day as a gift from Wakan Tanka. Is it right to use that wonderful gift in being worried and depressed about what is going to happen tomorrow? No, I will enjoy that day the best way I can, and if spending the money I have brings others or myself enjoyment, I will do it.

Before I went on the road to play ball, money meant nothing to me. I had no use for money. When we began to receive our portion of the gate receipts from each game we played, it didn’t impress me. I stuffed the bills into my pocket and really didn’t even know how much money I had. Eventually, though, my pockets were full, and it became a bother to me. I asked our manager what I should do with the stuff. He suggested that I send it home to my mother if I wasn’t going to spend it. I didn’t have anything to spend it on, so each week I sent the money to my mother. Even she had very little to spend it on and so she just kept it. Eventually though, I learned what that money could buy. It could buy things that I wanted. You notice, I did not say, things that I needed. There is a great difference between needs and wants. Needs are important, wants are not. For that reason, I say I have never really learned the value of money. Occasionally it takes care of needs, but more often it takes care of wants, and so it is not that important.

During this time, I knew I was going to be drafted by the army. Although my brother, Gus, went into the army, I refused. The words of Black Hawk, an old chief, come to mind when I speak of this. He said, “The path to glory is rough and many gloomy hours obscure it. May the Great Spirit shed light on yours – and that you may never experience the humility that the power of the American Government has reduced me to, is the wish of him, who, in his native forests, was once as proud and bold as yourself.” Many of my people did fight in World War II. Many of them were killed, many came back crippled for life, some just came back, and some even became heroes. Those who did come back, came back to oppression in their own land that was as great as any they were fighting in another land. My decision did not in any way lessen my pride in those who did go. They were doing what they felt was right, and I did what I thought was right. I could not comprehend fighting for what was once ours, to protect what was no longer ours.

It is a known fact that the United States Government has always been the first to break every treaty ever agreed upon between them and my people. Nearly every treaty made forbade the Indian to ever take up arms against a white man again. The exact words of one treaty signed in 1869 between Indians and whites is worded: “They will never again kill white men nor attempt to do them harm.” We did not have the right to fight alongside the white man. If I had chosen to take up arms against the United States Government, the treaties would have been valid, but since it was in favour of the United States Government, they were willing to forget the treaties. I refused to do it as a matter of principle. I did, however, go into the Merchant Service and serve in that capacity during World War II.

When the Sioux Travellers split up, we all went different ways. I went into pro ball. I played for various teams all over the country, but it just wasn’t the same. I was still good, I knew that, but I never did quite succeed. I was a born athlete, and that was my first love, so I eventually did anything that had to do with athletics. I played basketball, baseball, and even some football. I even tried boxing but found that my skin cut too easily. Eventually I began to realise that just being good at something was not enough for the white man. I also had to be like him, think like him, and even look like him. I finally decided that my reflexes were slowing down and I was getting too old to play ball anymore. It was then that I took on the “white man’s curse” called “work.” To me, “work” is a matter of your state of mind. Its the white man’s way of looking at it, my people “worked” very hard to survive during the , centuries before the white man arrived on our land. To my people, it was not considered “work.”

Each and every member of the clan or tribe did what was necessary for survival and it was not considered work, but was just a part of his or her life style. What they did for their own or the tribe’s survival was the natural thing to do, and they certainly did not understand the concept of being paid to do some- thing for someone else. Even today, Lakota people do not consider what they do for themselves as work, whether it be farming, ranching, housework, taking care of children, or whatever. But, if they do it for someone else and are paid for it, it is work. It is a concept we have learned from the white man and it goes against our natural feelings to be paid to do something, even though it is necessary for survival today.

I learned many things in the next few years. I learned to be a lumberjack, a performer in a Wild West show, a farmer, an ice-handler, a construction worker, a horse trainer, and I worked in a saw mill. One of the main things I learned, though, is that rarely was an Indian hired on a permanent basis. Indian people were hired for temporary labour and that was all. It mattered not where they had come from or where they went afterwards. When the job was done, the white man was through with you. I also learned that because I was an Indian, I was not supposed to know as much as the other people with whom I worked. It didn’t matter how well I knew how to do something; someone always told me how to do it. Having to cope with this attitude was very hard. From the time I started to school (except during my ball playing days) I had been told that Indians did not do things right. Only the white man could do anything right.

Today, I see young people on the reservation who I know have degrees in certain professions. Many of them are not working at those professions because they would have to enter the white society to do so. They have gone through college and learned the profession as well as anyone else, and yet there is always a white man telling them they are doing things wrong. Indian people are not aggressive, and they have a very strict inborn code of courtesy. It is not polite to argue with someone or to tell someone else they are wrong. It is better to agree with them at the time, and let them find out for themselves they are wrong, if in fact they are. To my people, it is rude for someone to tell you you are wrong. It is as if they are saying to you, “You are not very smart, and you will never get this right, or even realise you are doing it wrong. Therefore, I must tell you that you are wrong, and I must show you how to do it the right way.” So, many times the Indian goes home, back to the reservation, and tries to forget the rudeness and aggressiveness he has encountered.

I did not go back to the reservation to stay, although even today, I have to go back every so often to find peace of mind. There, I can sit with my people in silence and feel no uneasiness, or I can talk with them in Lakota and know I am being understood perfectly. I can eat fry bread and wojape and know that I am not attracting curious attention. I am called “Grandfather” or “Uncle” by all the young people, and it is perfectly natural. Most people see only the poverty on the reservations and this is because they look only at things in terms of material wealth. They do not see the love for the children, the loyalty of large families or the peacefulness of belonging that is there. At one time that same peacefulness could be found anywhere in this country. Now, it can only be found on the reservations where we are among our own.

Each time I left the reservation more determined to find a place for me in that white man’s world. At one time, when the government was trying to get people to leave the reservations and take jobs in cities and suburban areas, they were offering money for Indian people to go to college or a trade school. I took advantage of that, and went to college in Salt Lake City, Utah, for a couple of years. Later, I took more courses at the University of Nebraska. My brothers and I tried to go into business for ourselves, but our request for a loan was turned down. It would be hotly denied by the “city fathers” of that small town, that we were turned down because we were Indian, but they knew the truth, and so did we, even though it was unspoken.

No matter what I tried, there was always that same barrier. I was a grown man, but I was not trusted to do anything right, always told what to do and what not to do, and I almost said, treated like a child. But, I must amend that to be treated like a white man’s child. Indian people do not treat their children that way. I was not willing to stop being an Indian and become a white man. In fact, I was very much afraid to be like the white people. They seemed to have no roots anywhere, most of them didn’t know what nationality they were, or where their people came from, and what’s more, they didn’t care. Most white people seem like lost souls to me, who must continuously talk, be on the go, and get everything they can, in order to know that they exist. They live their lives in a frenzy of motion, and do not stop long enough to even know themselves. The thought of being such a person frightened me, and I felt sorry for them. But, putting philosophy aside, there was still the matter of survival.

During these years, I began to drink, and as time went on, I drank more and more. Alcohol is the death of my people. The alcohol is the tangible thing that causes death. The intangible things are despair, hurt, bewilderment, fear, and the inability to cope with the white society, and loneliness when away from the reservation. All of these things are felt by my people practically from the day they are born, and many of them become alcoholics by the time they are 30. Anyone who drinks knows that with alcohol, a person can forget, even if just for a little while. In the first place, most of my people never had the opportunity to learn how to drink. It was given to our ancestors for one purpose: to get them drunk. It was bootlegged to the first reservation people. When an Indian bought a bottle from a bootlegger, he drank it all immediately so he wouldn’t get caught with it, and this resulted in him getting very drunk. My people would have been quite surprised to learn that some people actually could and did drink only a mixed drink or two, and no more. A man couldn’t get drunk on that and they had learned that getting drunk was the only purpose of drinking. It wasn’t until 1953 that an Indian could walk into a bar and buy a drink.

I spent many years with the bottle. I built a complete life style around my drinking. I bummed and rode freight trains all over the country, and rarely stayed III anyone place long. In fact, I was usually not welcome in anyone place long. I was a hurt and angry drunk Indian, and although I never got into any serious trouble, I did shoot off my mouth a lot, the result of which was having first hand knowledge of most of the county jails all over the country. You see, when I was drunk, I forgot to be careful about doing something of which the white man didn’t approve. I worked spot jobs when I needed money, or when I decided it was time to sober up for a while. At a farm or two, I knew I could get seasonal work for the sure each year, and so I usually managed to end up there in the spring. Until the last year or so of my drinking, I never drank while on a job.

I went to work many times with one bad hangover, but I didn’t drink while working. In fact, many times during those years, I would decide to get myself straightened out, and I wouldn’t drink for sometimes six or seven months. But, something always happened and the bottle was there to help me forget. The last couple of years of my drinking were hard. I was getting older and I was tired: tired of always being on the bum, tired of sleeping under bridges and in cheap hotels, tired of wondering where my next bottle was coming from, and tired of waking up in a familiar jailor detoxification unit. I was familiar with every alcohol treatment centre and “detox” unit in two or three states, and could tell the counsellors what they were going to say before they said it. I had heard it all so many times. I was sick of it all: the alcohol, the white man, the bumming, the loneliness, and I was ready to go home. I had seen and done more things than a man should in a lifetime. I was ready to do what my Grandfather had told me so many years ago: “Come back home and be Lakota.”

So, with this in mind, I checked into the first detox unit I came to, which happened to be in a town in western Nebraska. I only wanted to get the alcohol out of my system and then go home. But, the next morning, a woman walked in the door who changed my plans somewhat. She worked as a counsellor at the detox unit. All those years, I had looked for a certain woman. I knew what she looked like because I had seen her many times in my thoughts. Yes, there had been many women in my life, but none of them were the one I was looking for. I had almost given up on ever finding her when she walked in the door. To make a long story short, she is now my wife, Shirley. Today, when people ask how we met and she tells them, I always tell them she doesn’t know what she is talking about. I met her many, many years ago in my thoughts and dreams. I knew exactly what she was like and what she looked like. It just took me a long time to find her, but I knew her long before I found her.

Chapter 3 The Circle Of Life

My wife is not Indian, she is a white woman. Yes, she grew up and lived in the white culture for many years, but inside she is more Lakota than a lot of Lakotas I know. She and I broke a lot of the white man’s unspoken rules when we got married, but we have always known that it was meant to be. There are just some things you don’t question. It is all a part of the Great Mystery. I don’t know why I carried her image for so many years, and I don’t know why when we met, we both knew almost at once that we were supposed to be together.

There is no way to explain these things. The Lakota word for the Great Spirit, or God, is Wakan Tanka. “Wakan Tanka” literally translates to “big, immense, or all-encompassing,” “mystery, or anything I cannot explain.” This is why we say strong unexplained feelings are “wakan,” or a part of the Great Mystery, Great Spirit, or God, if you prefer.

The idea that “wakan” means “holy” comes from the fact that anything my people didn’t understand was treated with great respect and awe. It did not pay to be flippant about anything you did not understand. We decided that since we both knew so much about alcoholism, learned from the school of experience, and taking courses at various Junior Colleges and Universities, we would go to the University of South Dakota in Vermillion and get a degree in alcohol counselling. In the spring of 1981 we were married on the Rosebud Reservation in Lakota tradition with a medicine man conducting the ceremony. Since marriage ceremonies performed by our medicine men are not considered legal, about a week later we went to a judge for the white man’s ceremony. To us, our wedding anniversary is on April 18, the day we were married by Lakota tradition.

Although we have not yet gone to live permanently on the reservation, in many ways, I have “come home.” Our marriage ceremony was the beginning. I started to recall the teachings of my grandfather. I realised that what he said was not so much in the manner of teaching, but more like a guideline. The answers to living a good and happy life do not come as much from the teachings of other men as from what Wakan Tanka has provided for us to learn from. The answers are all there in the animals, the insects, the trees and plants, rocks, water, wind, rain, snow, sunshine, the seasons, the sky and the earth. My grandfather gave me the guidelines for finding those answers, and I finally began to use them. During those years of trying to live like the white man, I was searching for answers and an identity that was not there. I had not taken the time to find the answers the Lakota way, and being Lakota, the white man’s answers just were not good enough. My identity was not in their ways.

After a year at the University of South Dakota, we came to Crazy Horse Mountain near Custer, South Dakota to work for the summer. We both loved the Black Hills and enjoyed the Ziolkowski family and what Korczak was doing, and the “work” we were doing so much, that we are still here. Remember when I said that “work” was a part of the life style with my people? That is the way my wife and I look upon our “work” here at Crazy Horse. To be sure, we are paid for it, because as I said, this is necessary for survival today, but beyond that, we have made “being on the mountain” a part of our life style. We do not go to “work”, we “go to the mountain.” It is a part of our contribution to the survival of my people. In the winter, during the off-season, I am at the entrance gate selling tickets. But, in the summer, I am in the Museum of the North American Indian, and I am right at home. I feel good in there because I am surrounded by the things of my people. My heart is in what I am doing, and no one tells me how to do it. My title is guide-lecturer, but to me, I am just talking to people, telling them about my people, and expressing my opinions about what I have learned through experiences in my life. Some of it is controversial, to be sure, because many of the people I talk to are locked into what I call “the white man’s square,” and I am looking at things through the circle of life of the Lakota.

If one takes careful note, it will be realised that Wakan Tanka has put nothing on this earth that is square. All natural things are round or curved, including humans. My people learned great truths from this. Our homes were round, our camps were set up in the round, we sat in a circle during council meetings, and danced our prayers and ceremonies in a circle; everything we did or made was round. We even viewed the life and death of all things in the round, hence, “the circle of life.” All life comes from the elements of this universe, and all life will eventually return to those elements. I am not just speaking of visible elements, I am also speaking of the spiritual.

My wife refers to this concept as “life force.” To me, it is simply Wakan Tanka. Man is born with the spirit of life in him, he lives through the four ages; infancy, youth, maturity and old age, and then he dies, and the spirit of life and the elements that make up his body go from him, back into the life force. The spirit of life creates new life to repeat the circle. It is never ending. All living things go through this cycle over and over again.

It appears to me that if the white man ever knew about this circle of life, he has forgotten it. When he first came to our land, he brought his “square” with him. Speaking in the white man’s words, to us this was “sacrilegious.” He was not paying attention to the teachings of Wakan Tanka. Everything he did was square. His houses were square, his doors and windows were square, his furniture was square, he arranged his villages with a “town square,” and he fenced the land in squares. This all seemed very strange to our ancestors, but it was later realised that even the books the white man learned from were square. He found his answers for living in a square book, and not through the teachings of Wakan Tanka.

From the day he is born, his life is in a square, each phase of his life is in neat little boxes within that square. His culture dictates that by the time he is a certain age, he must leave the box of infancy and enter the box of youth. He is an infant only so long as his culture tells him he is, and by the same token, he is a youth only so long as his culture allows. The good things of those youthful years must be left behind when he enters the box of maturity. His culture even tells him when he must enter the box of old age, and become no longer useful. He has no choice over these matters.

The decisions are made for him. His square Bible tells him that when he dies his spirit will go to heaven or to hell, depending upon whether he followed the rules of his culture in moving through the boxes of his life. To be sure, the chemicals of his body will go back to Mother Earth, but they are even stingy with that. A man is buried in a steel box to deny Mother Earth the use of his chemicals as long as possible. His spirit or life force does not stay here to help bring forth new life, and even the tangible elements of his life are selfishly boxed up: it is all take and no give!

It is for that reason that I tell people we know the white people will not be here for ever. When they die, their spirit goes to heaven or hell. It does not stay here. The Lakota spirit or life force stays here to help with new life, and so some day there will be no more white people here. It may take many centuries for it to happen, but it wil happen. A people cannot survive by only taking and not giving. Eventually, there is nothing left to take. We have a different concept of time than the white society. To them, 500 or even 1000 years is a long time, but to the Lakota, it is nothing. In fact, time has very little meaning to us. It has been very difficult for us to conform to the white culture’s rules on time. To eat, sleep, work, play and worship at a certain time is hard for us to understand. It makes more sense to eat when we are hungry, sleep when we get sleepy, work when it is necessary, play when we can, and meditate or pray any time our emotions tell us.

The white man’s concept of time fits very nicely into his square but it doesn’t fit at all in our circle. I do notice, though, that when the white man’s “time” is all gone, he fights it with his last breath. Indian people do not fear death. We know that, even after we die, our spirits will still be here and be a part of this beautiful land and its people. We are as eternal as all of nature. No wonder the white man is afraid to die. His spirit must leave here and go to a “better place,” or a worse one. But, they also tell me that this land is a “better place” since they have come here, and if that is an example of what they are talking about, I want no part of it. I would be scared, too.

I doubt very much if the Lakota will ever forgive being forced into the position of being a minority in our own land. The white society can force its education, its religion and its ways on us all they want to, but we will always be Lakota, and think and act Lakota. Our very creation is in this land and the lessons learned by our ancient ancestors of how to live peacefully with this land have been born into us. If a man has any Indian blood at all, he has some thoughts and feelings that are alien to the white man’s world but natural to this land.

I am sure that this concept of my philosophy will seem strange and even threatening to many white people, but keeping in mind the Lakota harmony with the land we were put upon, I believe it can be understood. When all people were originally placed on the face of this earth, they were put in a particular environment. Everything needed for their survival was provided for them by the Great Spirit. Each race of people had their own place. This is the way it was intended. But, when people forgot where they belonged and started going into other people’s lands, they found the environment hostile because they did not belong there. They had to fight not only the people, but the land in order to survive.

The white man has fought this land and its people since the day he arrived here. We understand that they must fight for survival continuously every day of their lives, because they are in a land hostile to them. This land was not made for them, it was made for us to belong to and not the white people. We lived in harmony with not only the land but everything around us for centuries. Everything was a relative and as a relative was treated with love and respect. This was not a fearful and hostile place to us because we belonged here. It was only after the white man came that this became a fearful and hostile place. Regardless of the white man’s religious teachings, we have always known that our misfortunes were as a result of their doings, and not a punishment from their angry God.

To this day, the white society is still changing things around to suit themselves, and they have all but destroyed this once beautiful land. They are still fighting the land openly, and its people, not so openly, but fighting them nevertheless. You see, they must keep firm control over the land and its people, for if they don’t, they think they will not survive. They are like a house plant that must be constantly tended or it will die. I always use the example of a tomato plant. It is not native to this land and if you put it in the earth among the trees and all the native grasses that grow here, and leave it alone for a couple of weeks, it will perish. When you come back, it will be dead, because it does not belong here. The only way it will survive is if you cut down the grasses around it, bring water to it and tend it daily. The white man is like that tomato plant. All things around him that are natural must be destroyed if he is to survive. My people have very different thoughts and beliefs about Wakan Tanka, the Great Spirit, or God. Yes, I use the three words interchangeably, depending upon to whom I am speaking, because, basically, I believe they are all one and the same. The Mysterious Power greater than man is the same in all of the universe. It is man who makes the distinction, not Wakan Tanka. The different words, thoughts, beliefs, practices and means of worship are all created by man, not God.

I have always felt that when people call their belief a “religion”, they have adapted that faith to the way they want to believe. Indian people are not like that. Our so called “religion” is, and always has been a way of life to us. We adapted ourselves to what we observed around us in nature. It was all very real, placed here by Wakan Tanka, and there was no thought of adapting it to what we wanted to believe. We totally adapted ourselves to what was here.

We know there is a Great Power and there are many things we do not understand. We see this Great Power in every living thing, and so, for that reason, every living thing is sacred to us. And, this may sound strange, but the life of the white man is sacred to us. We respect that life force or spirit that is in him, but we do not respect, and we cannot condone the things he does. His acts are not of the Great Spirit, they are of man and have been created by man. Even the Bible was created by man and so is no more perfect than anything else man creates. Only those things created by the Great Spirit are perfect.

Because we saw the Great Spirit in everything in nature, including ourselves, we had a very close relationship with the Great Spirit. We do not think of the Great Spirit in terms of a man form or in a specific place. We do not place the Great Spirit on some throne up in the sky. The Great Spirit is everywhere, so when we die and our spirit joins the Great Spirit, where does our spirit go? It must stay here to help the Great Spirit. When I say that every living thing has life, it also means things that many people do not consider as having life. It means the winds, the elements of weather, stones and mountains, water, fire, the sun and earth. All of these things are sacred and so are considered our friends and relatives.

I will relate the best example I can think of: I can remember seeing one of my grandfathers standing out in the open with his arms raised to the sky and facing a thunderstorm that was approaching. In Lakota, my Grandfather was saying, “Hau Kola! (Hello Friend!) It is good to see you again. I am happy that you are bringing rain to Mother Earth and her people. The earth is dry and we need the moisture. We are all grateful that you are coming.”

Chapter 4 Wakan Tanka And The Coyote

Nothing in our natural environment was considered alien. We were all relatives. Some of these relatives had powers that were harmful to us, and we understood that that was why we had a brain and thinking powers. Man is the most helpless of all creatures on this earth, and without his brain, he would not have survived. But, that does not mean that our thinking powers made us any better than the other creatures. Our brain is a gift from Wakan Tanka and is to be regarded with great respect and humbleness. It was not to be used for the wanton destruction of Mother Earth and the creatures Wakan Tanka put here. Because we had this gift, it was meant to be shared and used as a means of protecting these other relatives, and not destroying them.

Even obtaining our food and other means of survival was done with respect. A prayer was offered to the spirit of the animal, tree, or fruit-bearing shrub that we utilised for our survival. “Forgive me for my need,” was a part of the prayer, and again, I ask you to notice that we said “need.” It would have been very disrespectful to take something we only wanted. When something was taken in need, some portion was always returned in being grateful to the spirit. Today, some form of this can be seen at the more traditional gatherings of my people. Before food is eaten, a portion of every kind of food there is put on a plate and taken outside and given back to the Great Spirit. This is done with prayer in humbleness and gratefulness for the creatures and plants who gave their life for the food.

Most of our prayers are offered through the sacred pipe. The smoke from the pipe carries our words or thoughts everywhere so we always know they reach Wakan Tanka. The Lakota tell of Ptesanwin, White Buffalo Woman, who gave the gift of the sacred pipe: Two men were hunting, when, in the distance they saw something white and shining coming toward them. They first thought it was a white buffalo calf, but as it approached, they saw it change into a beautiful young girl, dressed in white buckskin. She was carrying a beautifully decorated pipe. Because one of the men was filled with desire for the woman, his flesh withered away and his bones fell in a heap on the prairie. The other man, his mind filled with awe and respect for her, was given the pipe with instructions for its use and care. There are several differing versions of this, but all are basically the same and accepted as true.

Altogether there were seven ceremonies in which the pipe definitely was to be used: Keeping of the Spirit, The Rite of Purification, Crying for a Vision, The Sun Dance, The Making of Relatives, Preparing for Womanhood, and The Throwing of the Ball.9 The old Lakota did not smoke in a casual manner, purely for pleasure or diversion. Smoking was not an individual indulgence, but one to be shared with Wakan Tanka and with other men. A man who went alone to fast, pray and seek a vision carried a pipe with him so he could share with the spirits around him. This was done by a young man seeking his first vision, by an adult at any time of trial or need, or by an old man seeking spiritual assistance when he was preparing to die. The pipe is not only sacred, it is also very personal to us, and pipe-carriers always have their pipes with them wherever they go.

The sweat lodge (The Rite of Purification) is a means of purifying not only our bodies, but our minds as well. The lodge is a small structure made of bent willows with heavy tarp over it. At one time, buffalo hides were used to cover the structure. After the people have crawled into the sweat lodge, very hot rocks are placed in a pit in the centre, and during the ceremony, water is poured on them, releasing steam much like the white man’s sauna. For us, this is a time of spiritual examination of ourselves. By means of meditation and prayer, we emerge from the sweat lodge, spiritually and physically a new and refreshed person. We purify ourselves in this manner before any important undertaking or ceremony, sometimes doing this on a regular basis. Purification for dancing in the Sun Dance can take several months or a year, before a person feels worthy enough to participate.

The Sun Dance is our most important ceremony. It is usually held the latter part of the summer. It is a time when the people come together for not only individual spiritual needs, but also for a collective supplication for pity and guidance for all the people. Much has been written and said about the Sun Dance of my people, and much of it is about the piercing of the flesh or flesh giving. Because this is a part of the Sun Dance that writers choose to take out of context to sensationalise, people have the idea that the piercing and flesh giving is the main part of the Sun Dance. This is far from the truth. Yes, it is a part of it, but the collective prayers of the people, not only the dancers, but the people watching as well, have more to do with the real meaning of the Sun Dance than does the piercing.

The Indian considers his body the only thing he owns and, consequently, offers his flesh as his most precious gift to Wakan Tanka. The piercing and flesh giving is an individual commitment, pledged by individuals for their own particular reason. Most people dance in the Sun Dance for “the survival of the people.” In the true meaning of the Sun Dance, it is a sharing of yourself for the good of the people. Although the method and structure of the Sun Dance is somewhat different from the way of our ancestors, the people still come together and camp, living in tepees, tents and campers for the four days. It helps to bond my people together in a common purpose, and is also a time of spiritual renewal and hope.

It has also been said that we worship the sun at this time, which is not true. The words we use for this event literally translate to mean, “Dancing, gazing at the sun,” which brings forth a very different meaning than do the words “Sun Dance.” It is a happy time for my people. Sharing, loving, and being grateful, not only with our human relatives, but with all our relatives in nature, helps to bring us back to reality of who we are and what our purpose is on this earth. If done properly, it is done away from the eyes of the curious white man.

We attempt to feel the things our ancestors felt and to renew our spiritual strength in the same manner they did. This then, is the basic structure of our “religion.” But, as stated before, to us it is not a religion. It is simply our way of life. We do not understand the concept of using one’s “religion” to impress, force, belittle, hurt, kill, and to use only when one is in dire need or danger. Our “religion” is the way we live our lives, and it has very little to do with the white man’s concept of religion. Among my people, each person is an individual. There are some guidelines we follow, to be sure, but each person finds his own method of living this life and what he believes in. He finds this not only through the experience of success and failures, but also through quiet thought, meditation and contemplation, and not by reading books so he can adopt another man’s truths.

Each man finds his own truth and he does not attempt to force it onto others, whether it be in everyday living or in spiritual thought and practice. A child is not told, “No, you cannot touch the stove because it is hot.” He touches the stove and finds out for himself that it is hot. That is one of his own truths. By the same token a man is not told, “You are wrong in what you are doing,” or ” the way you believe.” He will eventually find out if, he is wrong, and that is one of his truths. And what is a truth for one man may not be for another. This is an inherent freedom we have, and it is probably the only freedom we have that the white man cannot take away from us. He has certainly tried hard enough, but of all of the so-called minorities in this country, we are the only ones who have clung to our native traditions and life style, and refused to be like the white man. We have never acknowledged the white culture as being superior to our own. In fact, we feel it is a very inferior culture. My people are many times regarded as being not as intelligent or quick to learn as other races. The truth is, we are more intelligent because we have been quick to see through the white society’s so-called civilisation, how shallow much of it is and how very little it has to do with reality and truth.

A matronly white woman told me one day that her parents had come from Germany, and because they came to America, they gave up their German ways and became real flag waving Americans. She didn’t understand why the Indian people did not give up their ways and be “American.” She became quite uncomfortable when I pointed out to her that my people didn’t “come from” any other country. We were here, and those people who come here and think they have adopted the ways of this land are lying to themselves. All they have done is taken on a conglomeration of the ways of many lands that have been twisted, intermingled and mixed up until they are unrecognisable. The name “American” has been applied to this mixture, but it is not the ways of this land.

During my life I have been called many things: Radical, racist, prejudiced, stupid Indian, smart alack Indian; but rarely have I been called anything that would afford me the dignity of being a man with any sense. Through all this, I have come to realise that I was not put on this earth to become like the white man. I was born Lakota, in my own native land, and with a history and a heritage that goes back as far as any white man can claim. Many of my people have endured the same kind of life I have; some of them have fared better than I and some of them worse. Many of them have died trying to be a white man. I recall an old Lakota woman I know. She too, was taken to a missionary school as a young girl. She learned and she learned well everything they had to teach her.

For over 50 years she faithfully went to the Catholic Church and faithfully performed all the duties of a devout Catholic. One day, she quit going to the Catholic Church and started going to the reservation and taking part in the Lakota ceremonies and way of life. When asked about it, she said, “I was born Lakota, and now I am nearing my death, and I will die Lakota.” I am sure that many white people had patted themselves on the back when they saw her year after year in the Catholic Church. But, what had they really accomplished, except to force her to spend nearly all her life searching for something: peace, identity, somewhere she could be comfortable? It was only after she quit searching in the white man’s world and came home, that she found what she was searching for. She is Lakota. She always has been and she always will be, even after death.

Searching for an identity in the white society is a hard road for a Lakota who wants to remain a Lakota. We have one choice, if we want to “make it.” We must be like the white man. We have survived this long because most of my people have chosen to remember that they are indeed Lakota and so belong here. Our identity is in who we are and not in what the white society wants us to be. Some of us try to walk in two worlds and this is the most difficult. Many times, my thoughts and actions as a Lakota earn looks of scorn and derision in the white society. Through this long life, I have come finally to feel a great pity for the white man. I have more right to be here than they. Unconsciously, their feelings of guilt and not belonging are destroying them, and they are fighting back in the form of imposing their will over all of this land and its people.

In talking with people in the museum at Crazy Horse, I find many white people who are aware of this fact, and are searching for a way to reverse it. It is too late to undo the chaos the white society has caused in this land. I tell these people that the only way they will find peace and identity here is to search in the few places left that are as Wakan Tanka intended them. They will not find peace or identity in the white society any more than I did. Many of the white man’s children are beginning to see what their forefathers have done here and what is still being done. They are frightened, angry, hurt and disgusted, just as the Indian has been since the day the white man arrived. If the white children want self-identity in this land, they must find it in the ways of this land.

I am grateful and proud that I am Lakota, and if I had been able to see through the shallowness of the white man’s teachings, there never would have been a search for anything in their society. My identity is in being Lakota, and in the teachings of my ancestors, and the ways of this land. I am a part of this land. The assumption that this land can be owned is made only by the white man in his greed. Indian people have always felt that the land cannot be owned. We are not the only peoples on this land and when it is sold, the rights of the four legged and winged people, the rivers, trees and even the mountains are taken away. We don’t have the right to do that. The land is our Mother. We belong to the land, it does not belong to us.

People have asked me about the future nuclear destruction of life on this earth, and what I think of it. It will happen: of this I have no doubt. At one time it could have been avoided if the people of the world had realised how far from reality they were getting, and had come back to the ways of the Great Spirit. But, it is too late now. I think of it in the way of civilisation fighting its way to the top of a hill. Instead of heartlessly destroying every obstacle in the I way, the white man could have hesitated, stopped or turned back. Instead, they made it to the top, and now they are on their way down to their own destruction. There is no way to stop them or turn them back, because they are rapidly rolling downhill, and cannot stop at obstacles even if they try.

Yes, the white man will destroy life on this earth. He has been intent on doing that since he started up the hill of progress. The sad thing is that he is going to take all the other people and forms of life with him. But, in this country, we have a small, dog-like animal, called a coyote. Just as the white man has tried to do with the Indian, they have tried to exterminate the coyote. We have been brothers with the coyote for centuries and his ways are very much a part of our life style. White men have written many articles about the coyote, and why he is so hard to exterminate. One even went so far as to say that he believed it was impossible. He said that when the last man was gone from this earth, there would still be a coyote out on a lonely hill howling for his brothers. My only consolation in this is, wherever you find a coyote, you are going to find an Indian!!!

Jack Little, 23rd, November, 1984.