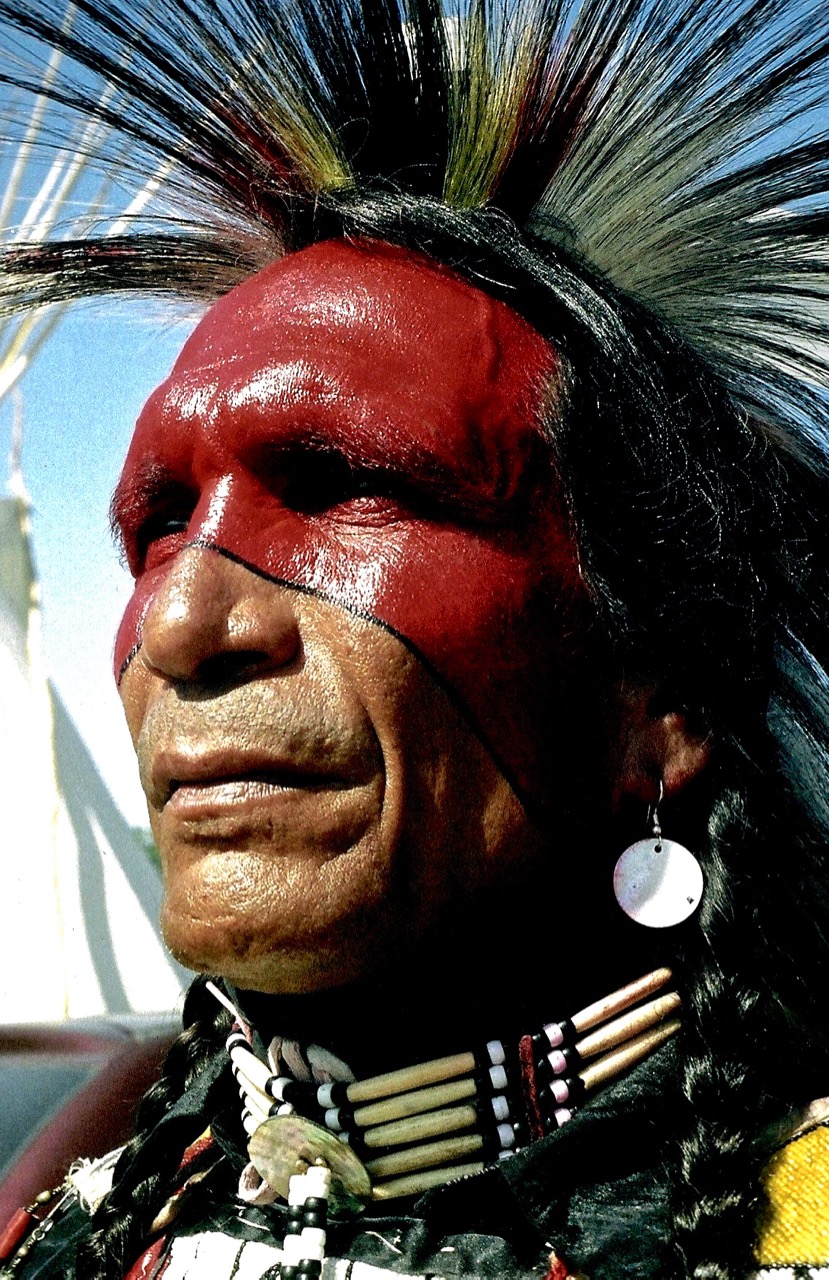

Beyone stereotypes: Photographer Andrew Hogarth talks to Erin O’Dwyer

about his passion for the Native American people

The Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, 19th July, 2008.

When Andrew Hogarth made his first trip to America in 1981, he was too shy to photograph the Native American people he had come to see. Instead, he concentrated his untrained camera skills on the desert landscape of the Great Plains.

“The Sioux are hard people to deal with,” he says. “One of the hardest things in life is to come between two societies and try to document them.”

A quarter of a century later, Hogarth has gathered more than 550 intimate portraits of Native Americans. His work has been shown in almost 30 exhibitions here and in the US and he has self-published six books documenting the modern life and historical battles of America’s first people.

The result is a 25-year retrospective of Hogarth’s work as part of the Healing Arts Program at St Vincent’s Hospital. More than 40 images are woven together with the stories of the late Jack Little, a Native American guide whom Hogarth first met at the Crazy Horse Memorial in South Dakota. It was Little who gave Hogarth rare access to the reserve communities and turned his hobby into a lifelong passion.

Officially, the exhibition spans 1981 to 2006. But Hogarth has just returned from his 13th trip to the States. It was a mercy trip to visit two sick friends and he went without his trusty Olympus OM20 camera. But he found himself at the Buffalo Bill Powwow in Cody, Wyoming, making the most of a small digital camera.

“I shot 37 people in 48 hours, and most of them were children,” he says incredulously. “They are just little digital images but a few are going to be added. So it’s actually going to be 1981 to 2008.”

Hogarth, 57, is an old-school photographer. He uses film – “it collects more detail than digital,” – and always shoots in natural light. He funds his own trips and gave up work as a newspaper printer to dedicate time to his art. Before he shoots, he asks his subject’s name, their tribe, and an address where he can send the photograph.

“There are 300 nations in America and many are intermarried so they’ll say Crow-Arapaho, Yakima-Cree-Umitilla or Mescalero-Apache,” he says.

“I introduce myself, then I stand at the edge of their personal space, then I take my lens closer. If everything comes together, then you have something that both individuals are proud of.”

Hogarth describes himself as a refugee from Scotland. He moved to Sydney in the mid-1980s, after he was retrenched from his job during the Thatcher years.

“I’m just a street kid from my own reservation in Edinburgh, Scotland,” he says. “I was thrown out of school when I was 15 and I educated myself. The Thatcher government devastated Scotland and no one cared. Much like no one cared what was happening in South Dakota. That has been one of the pluses in me being about to go into the reservations. I came from a similar style of background myself.”

Ironically, it was the films and television series of Hogarth’s childhood – Bronco, Maverick and Wagon Train – that gave him a fascination for Native American culture. But the images that beamed into his lounge room each night were vastly different from the Sioux landscapes that he saw when he boarded his first Greyhound bus bound for South Dakota in the early ’80s. “In the ’50s and ’60s, wagon trains were getting attacked three times a night,” he says. “But there were only a handful of wagon trains ever attacked. Indians never had guns and bad hairdos … it’s just pure stereotypes.”

Hogarth’s very personal approach to photography has required him to put his anger aside. He feels deeply about the plight of those he has photographed, but he hopes his audience will enjoy the images for their sheer beauty alone.

“You have to be very subtle when you ask people to be educated at someone else’s expense,” he says.

“As a journalist you can’t take one side or the other or you lose half your audience.”

Great Plains: Images of Native America 1981-2006 is at Xavier Art Space, St Vincent’s Hospital, Darlinghurst, from Monday until August 21. The exhibition supports St Vincent’s Healing Arts Program, with 20 per cent of proceeds going towards the hospital’s art collection.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.