National Library of Australia Card Number and ISBN 0-646-14651-3

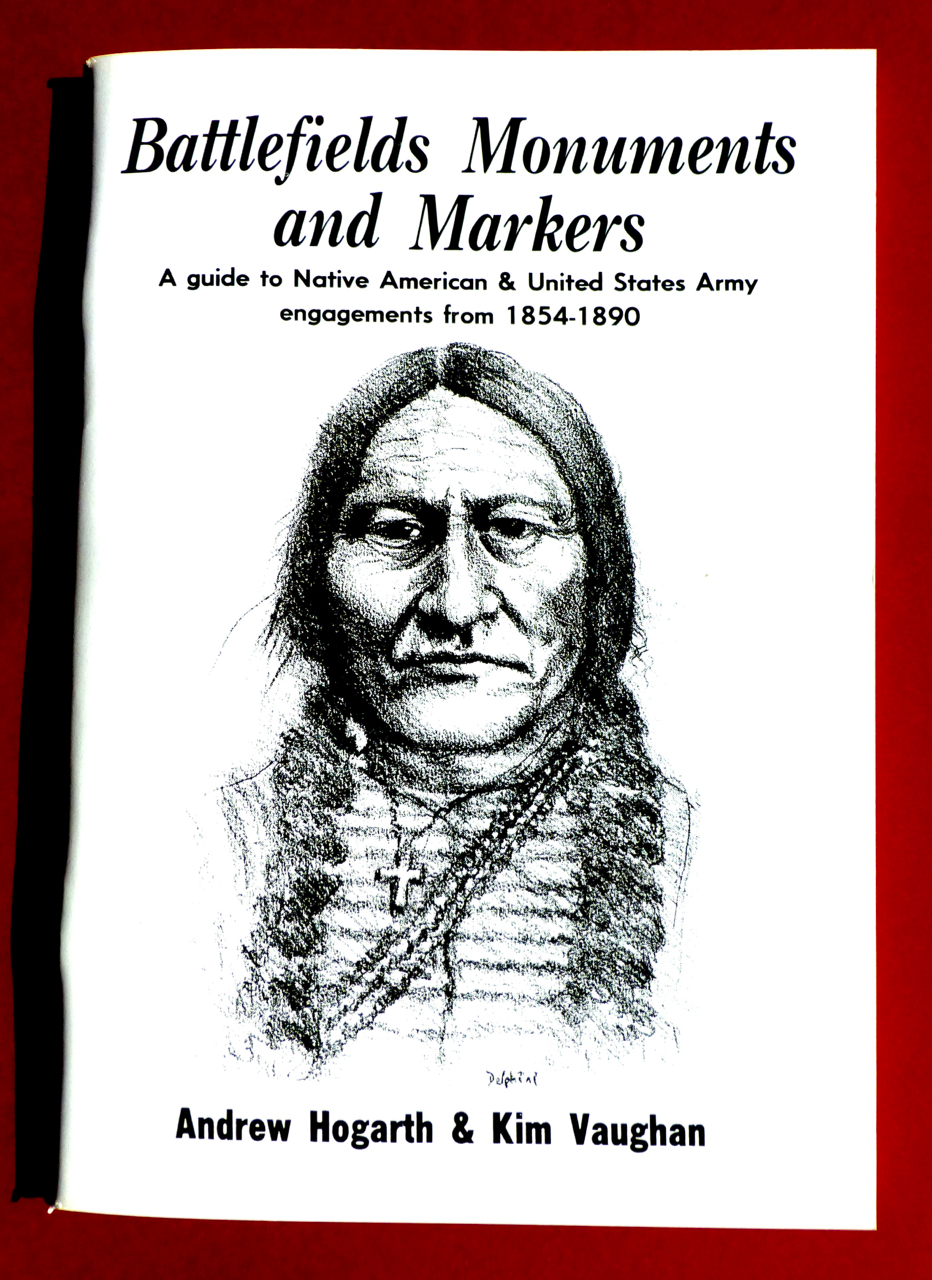

As recently as one hundred and thirty years ago the Great Plains of the United States of America was the homeland of the nomadic Native American tribes – the Lakota Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Crow, Shoshone, Pawnee, Kiowa, Nez Perce, Plains Apache and Comanche. Their traditional lands stretched from the Canadian border down into the Texas panhandle. The years 1854-1890 marked the height of European-Native American confrontation on the Great Plains. Battlefields, Monuments and Markers concerns itself with those years presenting to the reader over one hundred and twenty sites in a series of modern photographs, a brief history of the events and a guide on how to find these places. 100 pages, plus maps.

A determined survival

Book Review by Ethol Bohnhoff, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, 11th December, 1993.

All through recorded history of mankind the tenacity of the human spirit evidences itself against calamitous odds and events, leading to intended wholesale extinction of a class or nation, with survivors bruised, unbowed and unbroken, to record for future generations the monstrosity of human endeavours against them.

It is with surprise one reads of a “holocaust” preceding World War II – a “holocaust” of an earlier era whereby 6,000,000 native Americans were virtually exterminated. Some coincidence!

The present work is a guide to the resistance and battlefields of disjointed or combined tribes of American Indians against the aggressive newcomer in defending their native lands and lives. The conflicts, with heroism, treachery and loss of life on both sides, ceasing 100-odd years ago. Still in living memory of oral history of the American Indian and given rise to historical societies of USA citizens preserving physical evidence of deaths, garrisons and forts, besides enshrinement in printed works for posterity.

The authors provide a valuable objective guide to this unfolding segment of USA history and the native American Indian. Arrow straight in its direction, both in the printed word and visual content. Either as an historical landmark of general interest, or a stimulant to the curious and / or budding historian as a first guided step towards objective facts, including hidden truths now surfaced.

Simply a must: to be explored and cherished.

In 1990 I donated archived prints of my 1980’s battlefield images to Mary Ellen McWilliams at the Fort Phil Kearny/Bozeman Trail Association in Sheridan, Wyoming. Today they are housed at the Johnson County Library in Buffalo, Wyoming. For my generous gift I was later awarded the Fort Phil Kearny/Bozeman Trail Association Spur Club Award.

Medicine Wheel. The Medicine Wheel located high in the Big Horn Mountains is a mysterious remanent of an ancient culture. The wheel is made up of small and large stones placed in a circle with twenty-eight spokes. The circumference of the wheel is 245 feet. The wheel was first photographed in 1903 and since then debate about its origin and meaning have given no certain answers. The site was excavation in 1958 by solar physicist, John Eddy. A deep hole was found beneath the central cairn and it is possible that this held a vertical pole. Eddy proposed that the stone wheel and pole may have been used to gauge the position of the stars.

Other propositions put forward suggest the site was of ceremonial or religious significance. It may also have been used as a calendar. Crow Indian legend attribute the wheel to an ancient culture and its original use as unknown. Carbon dating suggests the medicine wheel was erected about 1200 AD. Location: Big Horn Mountains. En route from Lovell to Burgess Junction using Alt.U.S.14. Medicine wheel is located 3 miles north of the highway perched high in the Big Horn Mountains. Wyoming Sign posted.

Fort Union 1829. Fort Union was established by John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company in 1829. Located in North Dakota near the junction of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers the fort enjoyed much success and soon dominated the Upper Missouri fur trade. Much of this early success was due to the determination and vision of Scottish born Kenneth McKenzie. The American Fur Company encouraged travellers to visit the fort and much of the fort’s history is well documented in personal journals. In 1832 artist George Catlin spent time at the fort.

As well as painter Karl Bodmer, both recorded their impressions of life in and around the fort on canvas. Trade at Fort Union reached its peak during the late 30’s and 40’s. In 1857 the Assiniboin and Sioux living in the vicinity of the fort were struck by a smallpox epidemic. A reduced Indian population led to a drop in trade. In 1867 Fort Union was sold to the army. The fort was then dismantled and the materials used to build Fort Buford. Today, Fort Union is in the process of reconstruction. Location: Williams County, North Dakota. One and a half miles west of Fort Buford, south on U.S.2, fort in the process of being rebuilt with complete stockade fence. Museum. Operated by National Park Service.

Fort Laramie 1834. Fort Laramie was established by the Rocky Mountain Fur Company in June 1834. Originally named Fort William the name was changed in 1836. Under the leadership of William Sublette and Robert Campbell operations at the fort were a success. On the 26th June, 1849 Fort Laramie was sold to the U.S. army for four thousand dollars. For many years the fort was an important supply depot for travellers moving west. In 1851 and 1868 treaties with the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Shoshone and Crow were signed at Fort Laramie.

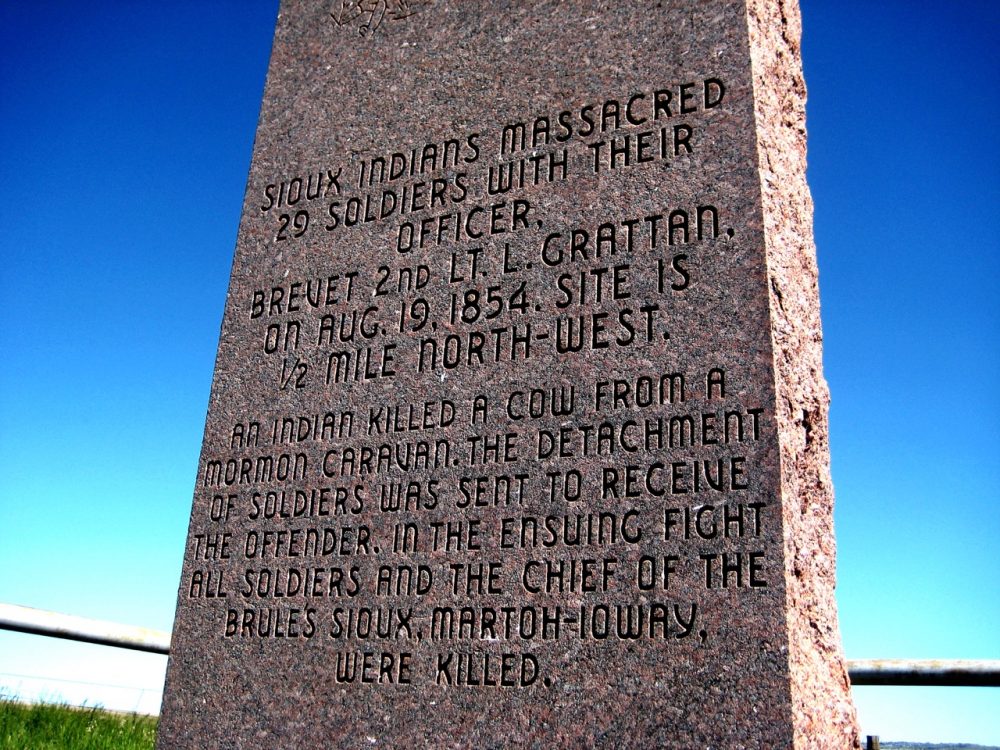

Hostilities with neighbouring Indian tribes were sparked by a single incident. On August 18th, 1854 a cow from a passing Mormon wagon train strayed into a Sioux village and was shot. The army ordered Lieutenant Grattan and twenty-nine soldiers to investigate the incident and arrest the warriors involved in the shooting. The Sioux resisted and in the fight that followed Grattan and all of his men were killed. Fort Laramie was abandoned in March 1890. Location: Two miles south west of the town of Fort Laramie on U.S. 26. Some original buildings restored. Museum and visitor centre. National Park Service.

Bordeaux Trading Post Nebraska Territory 1837. The trading post was established around 1837 by the American Fur Company. In 1849 it was taken over by James Bordeaux who ran it as an independent trading post for the Lakota (Sioux). From 1872 to 1876 it was operated by Francis Boucher, until the army discovered that ammunition was being sold illegally to Indians.

Bent’s Fort 1840. Bent’s Fort on the Santa Fe Trail in Colorado was owned and operated by brothers William and Charles Bent. It was a place of rendezvous for the Southern Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa and Comanche who gathered here during the early 1840’s to trade buffalo robes in exchange for basic goods such as flour, coffee and sugar. In the late 1840’s the army attempted to purchase the fort but unhappy with the offer and the effect of an increasing military and emigrant presence on his trade William Bent burnt the fort to the ground. William Bent then moved on to a new location hoping to re-establish his trade with the Indians. Location: Otero County, Colorado. Eight miles north east of La Junta on U.S.194. Completely restored historical site. Operated by National Park Service.

Fort Bridger 1843. Jim Bridger was born in Richmond, Virginia in 1804. At the age of eighteen years Bridger joined William H. Ashley’s expedition to the Rocky Mountains in search of beaver pelts. In 1843 Bridger and his partner Louis Vasquez built Fort Bridger near Lyman, Wyoming. With the decline of the fur trade the fort became an important trading post for westbound emigrants. In 1853 much of the fort was destroyed by fire. In 1858 the fort became a military post under the command of Colonel Albert Sidney Johnson and within a year the army had rebuilt twenty-nine of the buildings destroyed by the 1853 fire. The first newspaper published in Wyoming was printed at Fort Bridger. The second school in Wyoming Territory was opened at Fort Bridger in 1860. During the early 1860’s the fort served as a station for the Pony Express and Overland Stage. Jim Bridger died in 1881. Fort Bridger was abandoned on the 6th November, 1890. Location: Uinita County. Wyoming. Ten miles west of Lyman, south of interstate 801 U.S.30. Fort restored.

Horse Creek Treaty 1851. On a cold day in September, 1851 more than 10,000 Plains Indians gathered at Horse Creek for a council with the U.S. government. The council was organised by Thomas Fitzpatrick, a fur trader and Indian agent to the Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho. The aim of the council was the signing of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851. Horse Creek, thirty-four miles east of Fort Laramie was chosen as the site because there was insufficient grass near the post to graze the thousands of horses gathered. Tribes represented at the council included: Oglala and Brule Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Crow, Arikara, Assiniboin, Mandan, Gros Ventre and Shoshone. Location: Scottsbluff County, Nebraska. Two and a half miles north west of Lyman on U.S.26. Descriptive markers at site on highway.

Grattan Massacre 1854. The Horse Creek treaty of 1851 between the Plains Indians and the U.S. government was just three years old when hostilities broke out on the northern plains. On the 18th August I854 a Miniconjou Sioux High Forehead, while visiting his Brule Sioux relatives near Fort Laramie, shot and killed a cow which had strayed into the camp. The cow was from a passing Mormon wagon train. The owner complained bitterly to the commanding officer at Fort Laramie and demanded that action be taken against the offender. Second Lieutenant Hugh Fleming ordered Lieutenant John L. Grattan and thirty soldiers to investigate the matter and arrest those responsible for the shooting. Grattan fresh from West Point military academy did not hold a very high opinion of the Sioux and in fact let it be known that he considered the Sioux cowards. On reaching the village of Brule Sioux Chief Conquering Bear Grattan ordered his men into battle formation.

Through his drunken interpreter the young lieutenant then insulted and threatened the Sioux warriors who had come out from the village to meet with him. Conquering Bear tried to defuse the volatile situation that was developing between his young warriors and the soldiers. An accidental shot from the soldiers lines led to open fire from both sides. Conquering Bear was killed by an exploding shell from Grattan’s howitzer cannon. The Brule Sioux under the leadership of Spotted Tail eventually over ran the soldiers position killing every man. One badly wounded soldier did however make it back to Fort Laramie but he died later that eveping. The same day the Brule Sioux attacked the trading post of James Bordeau and only the timely intervention of Chief Little Thunder prevented the massacre of the Frenchman and his employees. Location: Wyoming. Ten miles south east of the town of Fort Laramie on U.S.26 to town of Lingle. Battlesite on county road eleven miles south of town. Two monuments. Private land.

Blue Water Creek 1855. In response to the Grattan incident, General William S. Harney and a force of six hundred men were ordered into the field to punish the Brule-Sioux. On September 2, 1855 Harney’s scouts located Little Thunder’s Brule and Oglala village of fifty-two lodges on the Blue Water Creek in southwestern Nebraska. Harney ordered his expedition commanders, Major Cady and Lieutenant Colonel Cooke to surround the village. In the parley prior to the attack Harney demanded the surrender of the warriors involved in the Grattan incident. In negotiations lasting nearly an hour a compromise could not be reached. With his troops already in position Harney ordered an attack. As the troops moved forward into the village the Brule and Oglala warriors retreated to the bluffs above the Blue Water Creek. Unable to hold this position with limited men and inferior weapons the Sioux were forced onto the open plain.

While the cavalry pursued the retreating Sioux across the open plain others returned to inspect their victory and search for survivors. The officer in charge of the search described the scene as one that defied description. In one cave alone seven women and three children were found dead. In the attack eighty-six Sioux were killed, five wounded and between sixty to seventy women and children taken prisoner. Chief Little Thunder escaped Location: Use local road to travel north of the U.S.26 from the point where the highway crosses the creek immediately west of Lewellen. No monument. Private land.

Bear Butte 1857. Bear Butte in South Dakota is a spiritual sanctuary of the Plains Indian tribes, in particular the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne. The butte and the area surrounding it was for centuries a select camp site of the Plains Indian. This land provided all the necessities of life, mountain spring water, wood, protection from the bitter north winds, plentiful game and wild fruits. In the summer of 1857 a grand council of Sioux was held at Bear Butte. The resolution of this council was to resist white encroachment into Indian lands especially the Paha Sapa’s or the Black Hills of South Dakota. Crazy Horse, an Oglala Sioux was present at this council and though still a young man was inspired by this plan of resistance and vowed to dedicate his life to this cause. Throughout the next two decades Crazy Horse rose to prominence and the Plains Indian showed great spirit and determination in resisting white advances into their lands. The high point of this resistance is considered by many to be the defeat of Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer and the 7th cavalry at the Little Big Horn in June 1876. Today, Bear Butte remains a place of spiritual importance for the Plains Indian. Location: Meade County, South Dakota. Three miles north of Fort Meade on U.S. 79, museum and walking trail. Operated by National Park Service.

Fort Larned 1860. The Santa Fe Trail was one of America’s most important routes west. During the years 1822 to 1880 millions of dollars worth of goods were passed overland on this route and a chain of forts was built to protect both travellers and traders. In June 1860 the U.S. army built Fort Larned to protect the Kansas segment of the Santa Fe Trail. The fort was also used as a base for many campaigns against the Plains Indians. General Winfield S. Hancock used the fort as a base camp for his 1867 campaign which was for the purpose of assessing the intentions whether peaceful or hostile of the various Indian tribes in the region. The result of Hancock’s campaign, the burning of a Cheyenne village at Pawnee Fork, served only to alert the Plains Indians to the doubtful intentions of the U.S. government. In 1868 General Sheridan, commander in charge of the U.S. army, sought and obtained permission from Washington to strike the winter camps of Indians south of Fort Larned in Indian Territory. Using Fort Lamed as a supply base Lieutenant George Armstrong Custer and the 7th Cavalry attacked a peaceful Cheyenne village under the leadership of Black Kettle on the Washita River.

During the years 1861 to 1868 the U.S. government allowed Fort Larned to be used as an agency by the Indian Bureau. Every autumn thousands of Southern Cheyenne, Kiowas, Arapaho and Comanche would erect their tepees in the fields surrounding the fort. Annuities given to the Indians included beef, bacon, coffee, clothing and blankets. The agency at Fort Lamed was closed in 1868 by which time all the southern tribes had been moved onto reservations in Indian Territory. The famous Santa Fe railroad continued its push westwards during the early 1870’s. Soldiers from Fort Lamed provided protection for the railroad construction workers. Six years after the completion of the railroad through the state of Kansas Fort Larned was abandoned. The fort was sold at a public auction in 1874. All of the original buildings are still standing. Location; Pawnee County, Kansas. Six miles west from the town of Lamed on U.S.156. Original fort in excellent condition. Visitor centre and museum. Operated by National Park Service.

Whitestone Hill 1863. Whitestone Hill Battlefield State Historic Site, located twenty-three miles southeast of Kulm, Dickey County, marks the scene of the fiercest clash between Indians and white soldiers in North Dakota. On September 3, 1863, General Alfred Sully’s’ troops attacked a tepee camp of Yanktonai, some Dakota, Hunkpapa Lakota, and Blackfoot (Sihasapa Lakota), as part of a military mission to punish participants of the Dakota Conflict of 1862. In the ensuing battle, many Indian men, women, and children died or were captured. The Indians also suffered the destruction of virtually all of their property, leaving them nearly destitute for the coming winter. That morning, Major Albert E. House, a Battalion Commander of the Sixth Iowa Cavalry, led a scouting party in search of Indians. In the early afternoon, their Metis guide, Frank LaFrambois, discovered a small encampment of Sioux on a small lake near Whitestone Hill. LaFrambois notified Major House of the find, who moved his battalion toward the village. Upon closer reconnaissance, House discovered that the “small” encampment included 300 to 600 lodges.

Frank LaFrambois and two soldiers were dispatched to notify General Sully of the discovery and to request reinforcements. While they were gone, the Indians detected the presence of the troops, and some of the villagers prepared to flee, while others prepared to fight. Major House, sent two reconnaissance parties to opposite sides of the tepee encampment to gather tactical information while he waited for the main column to arrive. For nearly three hours, an uneasy stand-off continued during which a delegation of Indian elders approached the soldiers and offered to surrender some of their chiefs. House, however, J insisted on total surrender, and negotiations broke down. Sully’s command was less than a mile away when the Indians saw them coming, and departure preparations became frantic. Tepees were stripped, travois were hastily attached to ponies and dogs, and possessions and small children were strapped to ninety-four travoises. Masses of Indians began streaming east, down a ravine that opened into a shallow mouth at the rear of the village.

It was nearly sunset when Sully’s troops reached the scouting party. As Sully’s main column advanced towards the village it became apparent that the Indians were escaping. Sully ordered Colonel Robert W. Furnas, commanding the Second Nebraska Cavalry, forward at full speed to cut off the Indians’ retreat. Stopping briefly to instruct Major House ‘to circle around to the left (north and east), Furnas directed his men around to the right (south), hoping to encircle the “village. Seeing that Whitestone Hill blocked escape to the south, Sully sent Colonel David S. Wilson, with part of the Sixth Iowa, to the north side of the village. General Sully, with one company of the Seventh Iowa Cavalry, two companies the Sixth Iowa Cavalry, and the artillery battery, charged towards the centre of the village. As they passed through the village, they captured a number of prisoners, who were left behind under guard.

Sully and his troops climbed to the top of Whitestone Hill to direct the rest of the battle and to offer artillery support, if needed by the soldiers on the flats below. Although the Indians scattered in as many directions as possible, most tried to escape down the ravine. As the Indians came to a saucer-like broadening of the ravine about one-half mile from the village, they began to gather in a large throng. There they were surrounded by Colonel Furnas’s cavalry, Major House’s battalion, and Colonel Wilson’s Sixth Iowa troops. Fearing that the Indians might escape in the impending darkness, Furnas ordered his men to dismount and advance toward the ravine on foot. When his men were, within a few hundred yards, he ordered them to begin firing. The other troops followed his lead, dismounted, and closed in on the Indians. Only Colonel Wilson’s men remained mounted, and, as the attack continued, their horses became wild and unmanageable. The Indians, noticing this weakness in the north firing line, suddenly charge in that direction.

Many were able to escape the deadly ravine. As darkness deepened, Colonel Furnas suspected that bullets from the other units were hitting his lines. He withdrew his troops to higher ground surrounding the deep ravine. As Furnas and his men withdrew, the other units also broke off the engagement and spent the night on the hilltops overlooking the battlefield. The light of the following day revealed a field of carnage. Dead and wounded men, women, and children, lay in the campsite and in the ravine. Tepees stood vacant or drooped in various stages of destruction. Camp equipment and personal items tools, utensils, weapons, toys, and injured or dying horses and dogs littered the ground Injured women protected babies and little children. As the soldiers looked after the wounded and gathered the dead, Sully moved his camp to the battlefield. While some squads of soldiers patrolled the region searching for escapees, other men were put to work digging graves and destroying the village and Indian possessions. During the Battle of Whitestone Hill, twenty soldiers were killed and thirty-eight were wounded. Although there was no accurate count of the Indian casualties, estimates ranged from 100 to 300 dead.

In addition, 32 men and 124 women and children were captured. For two days, military patrols guarded against reprisal raids while troops destroyed Indian property. Tepees, buffalo hides, wagons, travois, blankets, and perhaps as much as a half million pounds of buffalo meat were stacked and burned. Some of the fires were set over the graves of the soldiers to obscure the location of the burial places. Troops threw pots, kettles, weapons, and other things that would sink into the lake. On September 5, one of the scouting details ran into a party of Indians. In the ensuing skirmish, two more white soldiers were killed. The following day, Sully and his army marched south with their captives towards their transport on the Missouri River. The Indians who had escaped the battlefield scattered over the plains looking for friends and families who could share necessities during the winter months. Today, Whitestone Battlefield State Historic Site includes a portion of the battlefield, and a small museum with exhibits explaining the 1863 Sibley and Sully expeditions and the Battle of Whitestone Hill. There are two monuments, one honouring the Indian dead and a second commemorating the soldiers who died in the battle. A marker also recognises two early settlers, Tom and Mary Shimmin.

Killdeer Mountain 1864. After the establishment of Fort Rice on the upper Missouri River in July 1864, General Alfred H. Sully prepared to move his army against the Sioux. At this timethe Santee and Yanktonais Sioux were banded with the Teton Sioux after their defeat at Whitestone Hill in North Dakota and their flight from Minnesota. On the morning of the 28th July, 1864 General Sully’s scouts located a large Indian village at Killdeer Mountain in North Dakota. Many prominent chiefs were camped at Killdeer Mountain including Hunkpapa Chiefs Sitting Bull and Four Horns and Santee Chief Inkpaduta. With over twenty-two hundred men General Sully charged the village from the southwest. The Sioux with only lances, clubs, bows and old muskets rallied quickly. The Teton Sioux acted as a cavalry unit using their horses as was so necessary in plains warfare. The Santee and Yanktonais took cover in a ravine and took up positions as snipers. Although initially successful the Santee and Yanktonais were rapidly overrun by cavalry men on foot. The soldiers killed thirty Santee Indians.

The forest warfare tactics of the Santee and Yanktonais were inadequate on the open plains. The battle lasting some six hours was Sitting Bull’s first encounter with the white-mans army. The Sioux successfully covered the retreat of their women and children to an area some ten miles from the village before retreating themselves. Later that evening the Sioux staged a counter attack killing two soldiers. On the 29th July Colonel McLaren set fire to the Sioux village destroying the bands entire winter food supply as well as thousands of tanned hides and buffalo robes. McLaren and his men also killed hundreds of dogs still lingering in the camp and set fire to the surrounding forest. Perhaps the most notable act of bravery during the Killdeer battle was the actions of Sioux The-Man-Who-Never- Walked, a cripple since birth who demanded to be taken to the front lines so that he could prove his bravery as a warrior. His death song was short but proud. Location: Dunn County, North Dakota. Two miles north of Killdeer on U .S.22 signposted then eleven miles north west on gravel road. Monument and grave markers. Private land.

Fort Sedgwick 1864. Fort Sedgwick situated near the small town of Old Julesburgh in Northeastern Colorado was built in 1864. The fort was named in honour of famed Civil War hero General John Sedgwick who was killed in the battle of Spottsylvania. The fort was the centre of much activity for seven years. On the 7th January, 1865 both the fort and town were attacked by a large war party of Sioux and Cheyenne warriors. Fifteen cavalrymen were killed during this attack. A second unsuccessful attack on the fort occurred on the 2nd February. The Sioux and Cheyenne later captured and burnt the town of Old Julesburgh to the ground.

The town of Julesburgh was rebuilt on the perimeter of the military compound that surrounded Fort Sedgwick. A busy stage station operated from the town until the arrival of the Union Pacific railroad in 1867. With the arrival of the railroad Julesburgh became a centre for trade in buffalo hides and bones. In the summer of 1867 Lieutenant Kidder, Sioux scout Red Bead and ten soldiers were killed by Sioux warriors while carrying despatches from Fort Sedgwick to Lieutenant Colonel George Custer in Kansas. Fort Sedgwick was abandoned in 1871. In 1881Julesburgh was linked to Denver City by rail. Location: Sedgwick County, Colorado. Exit 172 interstate 76 for town of Ovid. Site of Fort Sedgwick situated one miles southeast of Ovid. Private land.

Fort Rice 1864. The fort was established on July 7, 1864, by General Alfred H. Sully as a field base during his 1864 expedition. The fort was named for Brigadier General James Clay Rice of Massachusetts who was killed at the Battle of the Wilderness during the Civil War. Fort Rice was the first of a chain of forts intended to guard northern plains transportation routes, evidence of the United States government’s changing policy toward these western lands, encouraging their settlement and providing protection for Euro-American settlers. Fort Rice became one of the most important military posts on the Upper Missouri River. It is located approximately thirty miles south of Mandan, Morton County. During the summer of 1864, Indians in Dakota Territory were angry and apprehensive about the military expeditions which had severely injured area Dakota, Lakota, and Yanktonai bands of the Sioux nation the previous year (see Sibley and Sully Expeditions of 1863). In response, the Indians increased their attacks on transportation routes, including steamboats travelling on the Upper Missouri.

In 1864 General Sully returned to the Upper Missouri with an army of 3,500 men to punish the Sioux, to force them onto reservations, and to strengthen the peace by building military forts near the mouth of Long Lake Creek (Fort Rice), at the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers (eventually Fort Buford) and near the mouth of the Powder River. The army hired fifteen steamboats to transport men and supplies part of the distance and retained three steamboats to support the expedition for its four month duration. Sul]y’s first action was to select a location for Fort Rice. The military reservation for the fort covered approximately 175 square miles (112,000 acres) and was established by Executive Orders of September 2, 1864, and January 22, 1867. The first structures were built by several companies of the 30th Wisconsin Infantry under Colonel Daniel J. Dill. Cottonwood logs, cut from the wooded banks of the Missouri River, formed the stockade, 510 feet by 500 feet.

Two log blockhouses, each twenty feet square, guarded the north-east and the south-west comers of the stockade. The fort buildings inside the stockade were built with cottonwood logs and had sod roofs. In the autumn of 1864, six companies of the 1st U.S. Volunteer Infantry arrived to replace the Wisconsin infantry. The “volunteers” were primarily Confederate prisoners of war, or so-called “Galvanised Yankees.” These prisoners enlisted in the Union Army to protect the western frontier rather than wait to be paroled or exchanged for Yankee prisoners of war or be sent north to work on government fortifications. Two companies of the similarly organised 4th U.S. Volunteers arrived as reinforcements in 1865, Upon the disbandment of the U.S. Volunteers, these units were replaced by Union volunteer troops (state militia) and after the war by troops of the “regular” army.

Life was not easy in these small frontier forts, isolated by distance and a seasonally ice-bound transportation system. During the fort’s first year, eighty one men died: thirty-seven from scurvy, twenty-four from chronic diarrhea, three of typhoid fever, ten of other diseases, and seven killed in combat, To pass the time during the first winter, the soldiers opened a theatre, and from June 15 through October 9, 1865, they published their own newspaper. Throughout its existence, Fort Rice was a highly active military post. It served a base of operations for General Sully’s First and Second Northwestern Expeditions of 1864 and 1865. In 1866-1868, important Indian councils were held at the post. The most important of these was the Great Council with various Sioux bands in July l868 I Although a key leader of the Lakota Sioux, Sitting Bull, refused to participate, Father Pierre Jean De Smet did convince Sitting Bull to allow his chief lieutenant, Gall, to attend this council. As a result of this council, area Sioux bands signed the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, which ended the Red Cloud War and defined the boundaries of the Great Sioux Reservation.

The reservation included most of the area west of the Missouri River in present-day South Dakota. In 1868 Fort Rice was expanded to cover an area of 864 feet by 544 feet. It was protected by a ten-foot-high log stockade on three sides and by the Missouri River c the east. Within the stockade and surrounding the parade ground were four company barracks with kitchens, seven officers’ quarters, a post hospital, bakery, storehouse library, and a powder magazine. Outside the east line of buildings were the guardhouse and post headquarters. Various other structures stood between these buildings and the stockade, such as company sinks (privies), laundress quarters, and bathhouse. Outside the stockade were the stables, barns, corrals, blacksmith shop, Indian scout quarters, and the post-trader’s store. The new barracks were made of pine lumber, but all other buildings were built from locally sawn cottonwood boards. Some were insulated with homemade ado bricks stacked between the wall studs. Clapboard siding and shingled roofs complete the improvements. Although the fort was designed for four companies of infantry, it was later modified to accommodate several companies of the 7th U. S. Cavalry.

While the average garrison was 235 men, troops ranged from a high of 357 in 1874 to a low of 61 in 1878. Throughout the history of the fort, the soldiers guarded against Indian attacks. Warriors assaulted haying and logging parties and raided the horse and cattle herds the army and of civilian traders. These raids continued as late as 1877. Between 1871 and 1873, Fort Rice served as the base for the First, Second. A Third Yellowstone expedition, which escorted parties surveying the route of the Northern Pacific Railroad. Four companies of the Fort Rice contingent of the 7th Cavalry accompanied Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer on his Black Hills expedition 1874. Two companies of Fort Rice’s 7th Cavalry troops fought in the Battle of Little Bighorn.

The post was abandoned on November 25, 1878, after the establishment of Fort Yates on the Standing Rock Agency. In 1913 the State of North Dakota acquired Fort Rice, and in the 1940s, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) marked the foundations of many of the Fort Rice buildings. None of the original buildings or structures remain at Fort Rice. Visitors will see depressions, foundation lines, and WPA corner markers. A brief history of the fort and a map appear on a site marker. Location: Morton County, North Dakota. Site located between Mandan and Fort Yates on U.S.1806. Descriptive markers and monument. State Park.

Fort Dilts 1864. Hundreds of settlers were killed in the Minnesota Uprising of 1862. The Santee Sioux responsible for the attacks fled west into Dakota Territory. The United States government responded by ordering Generals Sully and Sibley into the field. General Sully adopted a “scorched earth” policy indiscriminately attacking hostile and non-hostile bands of Sioux. A wagon train led by Captain James Fisk left Fort Rice located on the banks of the Missouri River in August, 1864. Fisk had only been able to get a small escort of fifty men from the fort commander. On September 2, 1864 while crossing Deep Creek one of the wagon overturned. Fisk ordered a second wagon, nine soldiers and three teamsters to remain at Deep Creek to reinstate the wagon while the other ninety-five wagons with its near one hundred and seventy emigrants and reduced cavalry escort continued its trek westward.

The small party was quickly attacked by a sixty strong band of Hunkapa-Sioux led by Sitting Bull that had been trailing the wagon train. During the hand to hand fighting Sitting Bull was shot through the left hip with the bullet exiting out the small of his back. Scout Jefferson Dilts and Corporal Thomas Williamson both suffered multiple wounds that would prove fatal in later days. Nine soldiers and teamsters and nine Hunkapa-Sioux were killed and mortally wounded during the fighting. Fisk corralled the wagon train on September 4 and for sixteen days waited for reinforcements from Fort Rice. Williamson and Dilts died on the eighth and nineteenth of September. During the siege the Sioux attempted to ransom white captive Fanny Kelly. The Fisk expedition was rescued by Colonel Dill and his eight hundred strong cavalry and infantry.

Sand Creek 1864. Indian hostilities against white settlers were both frequent and widespread during the first six months of 1864. The Southern Cheyenne were fighting desperately to stop the white-man from destroying their buffalo hunting grounds. In an attempt to stop the attacks, Governor Evans of Colorado ordered that a regiment of one hundred-day soldiers be raised from volunteers. A more conventional force could not be employed as’ many soldiers were involved in the Civil war and Indian war parties had successfully cut off the mail supply to Denver for a six week period from 15th August to 29th September,1868. Cheyenne Peace Chief Black Kettle and his followers who chose not to fight with the whites had set up a camp thirty-five miles northeast of Fort Lyon at Sand Creek. The peaceful Cheyenne village consisted of one hundred lodges sheltering some five hundred people. Without warning Colonel Chivington and seven hundred and fifty men attacked the village on the 29th November, 1868. As the soldiers launched their attack Black Kettle raised an American flag over his lodge.

The American flag did not stop the massacre. The soldiers fired indiscriminately at men, women and children. One hundred and thirty-seven Indians were killed during the six hours of fighting, the majority of which were women and children. Black Kettle’s wife was shot nine times but miraculously survived. The soldiers did not stop at killing but proceeded to scalp and mutilate many of the bodies. Nine Cheyenne chiefs died in the massacre including White Antelope, Warbonnet, Yellow Wolf and Arapaho Chief Left Hand. The massacre at Sand Creek intensified hostilities between the whites and Indians but it would take another five years before the white-man could claim an ultimate victory. Location: Kiowa County, Colorado. Eight miles north then one mile east of Chivington (U.S.96) on unimproved road. Monument. Signposted. The site is run by the National Parks Service.

Platte Bridge Station 1865. Platte Bridge Station located in eastern Wyoming two hundred miles west of Fort Laramie was a small outpost under the command of Major Martin Anderson. The 11th Kansas cavalry was garrisoned at the station during the year of 1865. During the winter months of 1864 the Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho of the Tongue and Powder River regions planned a strike against the Platte Bridge Station. With the arrival of the warm summer months a large war party of over three thousand warriors under the leadership of Crazy Horse, Roman Nose and High Backed Wolf concealed themselves in the bluffs surrounding the station. On the morning of the 26th July, 1865 Lieutenant Caspar Collins and twenty soldiers left the station to escort an approaching wagon train. After crossing the bridge just outside the station Collins and his men were both confronted and cut off by the warriors.

Collins ordered his men to charge the warriors and in the hand to hand combat that followed five soldiers were killed including Caspar Collins and eight seriously wounded. The soldiers in the wagon train under the command of Sergeant Amos. J. Custard quickly corralled their wagons for protection. Roman Nose and his warriors attacked the wagon train on foot and in a battle lasting four hours Sergeant Custard and twenty-three men were killed. Two soldiers escaped by swimming the river to safety. In both assaults it is estimated that between thirty to sixty Indians were killed. Location: Natrona County, Wyoming. Located in downtown Caspar, three miles west of West 13th Street and Fort Caspar Road. All the buildings have been rebuilt by State Historical Society. Museum and bookshop.

Tongue River 1865. In the summer of 1865 General Patrick E. Connor organised three columns of troops to move into the area around the Powder and Tongue River in eastern Montana with the hope of subduing the Sioux and Cheyenne. Colonel Nelson Cole and his column of soldiers left their base camp in Nebraska and started for the Black Hills of South Dakota. The second column of soldiers under the command of Colonel Samual Walker moved north from Fort Laramie with the intention of joining Colonel Cole in the Black Hills. General Connor and the third column of soldiers chose the Bozeman trail to lead them into Montana. In central Wyoming Connor and his men constructed a fort on the Powder River to use as a supply base from which to make their strikes against the Sioux and Cheyenne. One week after leaving the newly constructed fort Connor’s Pawnee scouts located a peaceful Arapaho village on the banks of the Tongue River in Wyoming. On the morning of the 29th August, 1865 the army attacked the unsuspecting Arapaho village of two hundred and fifty lodges.

Arapaho Chief Black Bear rallied his warriors who during the hand to hand fighting managed to form a defensive line enabling many women and children to escape. Between fifty to sixty Indians were killed including Black Bear’s son. The Arapaho horse herd of over three thousand head was reduced by one third due to theft by Connor’s men. The army lost eight men during the attack. As the Arapaho warriors retreated to the surrounding hills General Connor ordered the village to be burnt. The Arapaho lost buffalo robes, weapons, regalia and their stored food supply. A counter attack by the warriors failed as Connor made use of his Howitzer cannons. Location: Sheridan County, Wyoming. Located in town of Ranchester. U.S. 90 exit 9. Well sign posted. Battle-site now a park and camp-ground. Monument and descriptive marker.

Fort Reno 1865. Fort Reno was established in August 1865 by General Patrick E. Connor during the Powder River campaign of that same year. The fort was originally named for General Connor but the U.S. army later changed the name to honour General Jesse L. Reno. The fort was one of three built during the period 1865 to 1866 to service the Bozeman Trail. Fort Reno was abandoned in 1868 as part of the 1868 treaty. Under this treaty, Sioux Chief Red Cloud demanded that the Bozeman Trail be closed to emigrant travel and the three forts be abandoned and destroyed. Location: Eight miles south of Buffalo on Interstate 25 exit 291 then approximately Thirty-three miles south east on paved road through farmland. Monument. Can exit through town of Sussex.

Fort Phil Kearny 1866. Fort Phil Kearny was built by Colonel Henry B. Carrington and the eighteenth infantry regiment in the summer months of 1866. The fort was named in honour of Major General Philip Kearny who was killed at the battle of Chantilly on the 1st September, 1862 at the height of the Civil war. The fort was one of three built on the Bozeman trail which was the major route west from eastern Wyoming to Montana. The other two forts built were Fort Reno and Fort C.F. Smith. The three forts were built with the intention of protecting the many emigrant wagon trains moving west from attack by the Sioux and Cheyenne who inhabited the region. The land surrounding Fort Phil Kearny traditionally belonged to the Crow but by the early 1860’s the powerful Teton Sioux had pushed the Crows further west towards the Yellowstone River.

During its two years of operation Fort Phil Kearny was under constant attack from Red Cloud and his Sioux warriors. The Sioux and Cheyenne made a total of fifty-one attacks killing over 154 soldiers and civilians. Over 830 head of stock were also stolen. After the Fetterman massacre in December 1866, officials in Washington decided that seeking peace with the Sioux and Cheyenne would be a less expensive proposition than prolonged war. In the winter of 1868 Red Cloud and his chiefs signed a treaty with the U.S. government at Fort Laramie. One of the conditions of this treaty was the abandonment of the forts on the Bozeman trail. Fort Phil Kearny was abandoned in August 1868. Location: Johnson County, Wyoming. Approximately 17 miles south of Sheridan on U.S. 87, then a short distance west on Valley Road. The fort is well sign posted. Visitor centre, museum and interpretative display. Operated by Fort Phil Kearny/ Bozeman Trail Association. The front of the fort stockade has been rebuilt.

Crowheart Butte 1866. The Wind River basin in Wyoming was a prime hunting ground for the Shoshone, Bannock and Crow Indians. The Crow were traditional enemies of the Shoshone and Bannock. In March 1866 a battle was waged near Black Mountain to establish supremacy of the region. Led by Chief Washakie the Shoshone and Bannock were victorious. After the battle the area was named Crowheart Butte as it is rumoured that Washakie displayed a Crow Indian’s heart on a lance during the war dance that followed. Washakie was born of Flathead and Shoshone parentage around 1800, the exact date is unknown. Washakie favoured peace with the whites. Perhaps Washakie’s most noted act of bravery was the daring rescue of the seriously wounded officer Guy V. Henry during the battle of the Rosebud in 1876. When Washakie died in 1900 he was given a full military funeral and the rank of captain was bestowed on him. He is buried on the Wind River Reservation. Location: Fremont County, Wyoming. Fifty-seven miles northwest of Riverton on U.S.26/287. Roadside marker. Crowheart Butte one mile north.

Fort Buford 1866. Fort Buford situated near the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers was established on June 13th, 1866. The fort played an important role in the protection of river trade and the subduing of local Indian tribes. During its first year of operation Fort Buford was under constant threat of attack. Indian war parties frequently attacked the wood cutting details sent from the fort. Day to day activities of the fort centred largely around its role as a supply depot for the U.S. army’s campaign against the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne who were victorious at the Little Big Horn. Sitting Bull and his followers surrendered at the fort after returning from exile in Canada. Sitting Bull struggled to maintain his independence, but lack of natural game for hunting and the desire of his people to return to their relatives led him to return to Dakota Territory Thirty-five families, 187 people in all, travelled with Sitting Bull to Fort Buford, when on July 20, 1881, the great Sioux chief surrendered his Winchester .44 calibre carbine to Major D. H. Brotherton, Fort Buford’s commander.

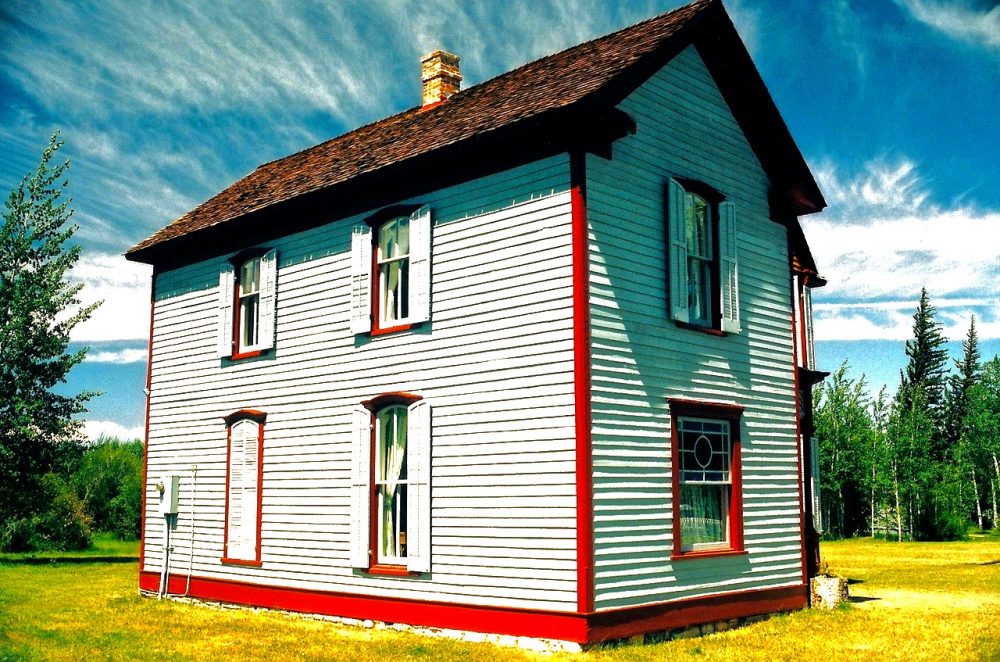

The role of the army at Fort Buford for the next fifteen years was to protect survey and construction crews of the Great Northern Railway, to prevent Indians and Metis from crossing the international boundary from Canada, and to police the area against outlaws. By 1895 the Fort Buford buildings were so dilapidated that repairs were deemed too expensive to undertake. Because the fort was no longer necessary for the mission of the army, it was abandoned on October 1,1895. Currently, three original buildings stand at Fort Buford State Historic Site: the stone powder magazine, wood-frame officers’ quarters, and a wood-frame officer the guard building. Inside the officers’ quarters is a museum exhibit and interpretive centre featuring artefacts and displays about the frontier military and Fort Buford’s role in the history of Dakota Territory. Location: Williams County, North Dakota. One mile south west of Buford on unimproved road, near Montana State line. Three original buildings. Operated by North Dakota State Historical Society.

Fort C. F. Smith, 1866. Early in August 1866 Colonel N.C. Kinney in command of companies D and G of the 27th U.S. infantry left Fort Phil Kearny to head north into Montana and establish Fort C.F. Smith. The fort was the third to be built along the Bozeman Trail. It was constructed from adobe bricks with the stockade measuring 125 yards square. Throughout its two years of operation Fort C.F. Smith was constantly under attack from the Sioux and Cheyenne of that region. C.F. Smith remained an autonomous body with the distance from other command posts making communication difficult and unreliable. The fort was abandoned on the 20th July, 1868. Location: Big Horn County, Montana. Forty miles south west of Crow Agency on county 313. Monument. Crow Indian Reservation.

Fetterman Battlefield 1866. Fort Phil Kearny had been kept under almost constant siege by Red Cloud and his Sioux warriors since its establishment in the summer of 1866. On the 21st December, Red Cloud baited Colonel Carrington into thinking the fort’s wood cutting detail was under attack. Captain William Fetterman and eighty one men were promptly despatched from the fort to rescue- the detail. On leaving the fort, Fetterman encountered two small decoy parties under the leadership of Crazy Horse and Hump riding towards the fort. Fetterman ordered his men to pursue the warriors and so was enticed into Red Cloud’s plan. Red Cloud had over two thousand warriors I waiting in ambush at Peno Creek three miles from the fort.

As the soldiers passed over Lodge Trail Ridge they were no longer visible from the fort and were quickly attacked by Red Cloud’s warriors. Within one hour Captains Fetterman and Brown, Lieutenant Grummond and the seventy nine men were dead. Both Fetterman and Brown committed suicide and it is thought their actions were in preference to possible torture by the Indians. Sixty warriors were killed in the battle. As winter temperatures dropped to below thirty degrees a detail was sent to Massacre Hill to recover the bodies and veteran scout John Phillips was sent south to Fort Laramie with a request for aid. The Fetterman massacre gave Red Cloud and his Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors the distinction of inflicting the worst defeat over the U.S. army in the west. Location: Johnson County, Wyoming. Five miles north of Fort Phil Kearny on U.S.87. Descriptive marker, the monument is on the east side of road.

Medicine Lodge Treaty 1867. In the summer of 1867 a meeting of Indians and U.S. government peace commissioners took place at Medicine Lodge located on the Medicine River in western Kansas. Southern Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, Plains Apache and Comanche were the tribes represented. The treaty was signed on the 21st October, 1867. Indian leaders present at the signing were Black Kettle, Little Robe, Little Bear (Cheyenne), Satank (Kiowa), Ten Bears and Silver Brooch (Comanche). It was the first treaty that did not ask the Indians to relinquish further land to the whites. Location: Barber County, Kansas. Town of Medicine Lodge built over Indian village/treaty grounds just south of town. Private land. Monument down town outside high school.

Fort Fetterman 1867. Fort Fetterman was established on July 19th, 1867. The fort was named in honour of Captain William J. Fetterman who was killed by Sioux and Cheyenne warriors near Fort Phil Kearny on the 21st December, 1866. The first commander of Fort Fetterman was Major William M. Dye who had under his command four companies of the fourth infantry. The fort acted as a centre of operations during the 1876 campaign against the Sioux under the leadership of Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. General Crook used the fort as a base for three of his expeditions into the Powder River country which was a stronghold of non-agency Sioux and Cheyenne. Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie also used the fort as a supply depot during his campaign against the Northern Cheyenne under the leadership of Dull Knife and Little Wolf. Many famous characters such as Jim Bridger, Calamity Jane, Buffallo Bill Cody and Wild Bill Hickok made frequent visits to Fort Fetterman. Location: Eleven miles north west of Douglas on U .S.93 above the valley of La Prele Creek and the Platte River. Three original buildings. Operated by S.H.S. Museum.

Hayfield Fight, 1867. On August 1, 1867 a large Sioux and Cheyenne war party numbering some seven hundred warriors attacked nineteen soldiers and civilians who were cutting hay two and a half miles east of Fort C.F. Smith. The small hay cutting party under the command of Lieutenant Sternberg were working as contractors for Fort C.F. Smith. The group had previously built a corral of logs and willow for protection in the event of an attack. With the aid of recently issued Springfield breech loading rifles the group were able to maintain a solid fire against the warriors. The fight lasted eight hours. Lieutenant Sternberg was killed early in the fight and civilian Al Colvin then took command.

The commanding officer at C.F. Smith even though aware that a fight was in progress refused to send out reinforcements so as not to leave the fort undermanned and vulnerable to attack. By late afternoon his resolve faultered and a relief force was sent. Two soldiers and one civilian were killed in the fight. The number of Indian fatalities reported varies dramatically. Reports range from as low as eight to as high as seventy. Location: Big Horn County, Montana. Thirty-eight miles south west of Crow Agency on county 313. Monument. Crow Indian Reservation.

Wagon Box Fight 1867. Wood for Fort Phil Kearny was obtained from Piney Island some six miles west of Fort Phil Kearny. On August 2, 1867 a war party of around one thousand warriors under the leadership of Red Cloud attacked the wood cutting detail. In an attempt to protect themselves, Captain Powell and his thirty-two men quickly corralled the wagon boxes. Recently issued Springfield breech loading rifles enabled the vastly outnumbered soldiers to maintain a rapid fire against the warriors. The engagement lasted about seven to eight hours. Lieutenant Jenness and privates Doyle and Hagerty were killed during the engagement. Sioux casualties were heavy, but an exact figure has not been established as many of the dead and wounded were removed from the field during the action. Location: Johnson County, Wyoming. West of Story off U.S.87. Monument. Signposted.

Fort Hays 1867. At the end of the Civil War the lure of gold, land and opportunity in the west initiated a mass migration across the United States. Settlers quickly began to push into central. and western Kansas and the U.S. government attempted to provide protection by building a series of forts on the Santa Fe Trail. Fort Hays was built in 1867 after a flash flood had virtually destroyed old Fort Fletcher. Fort Hays had no fortification walls and all the buildings surrounded the parade ground. The garrison at Fort Hays averaged three companies or two hundred and ten men. Many famous army generals and officers spent time at the fort including George Armstrong Custer, Marcus A. Reno, George A. Forsyth and Philip H. Sheridan. By the late 1880’s many Indian tribes were settled on reservations and so the Indian threat had ceased to be an issue. Fort Hays was abandoned on the 8th November. 1889. Location: Ellis County, Kansas. The fort is adjacent to the Hays golf, course on county 170. Three original buildings still stand. Visitor centre and museum (located in old blockhouse) operated by Kansas State Historical Society.

The Kidder Fight 1867. On June 1. 1867. Lt Colonel George Custer left Fort Hays in central Kansas with 1100 men of the 5th Cavalry. Custer had orders to subdue the Sioux and Cheyenne plains Indians who had constantly threatened white homesteaders in the region for the past three years. The main body of Sioux involved in the hostilities were led by Pawnee Killer. On June 29. General William T. Sherman. commander at Fort Sedgwick near Julesburg. Colorado. gave despatches to Lt Lyman S. Kidder for delivery to Custer. Kidder left Fort Sedgwick with a 10-man escort and Red Bead. a Sioux Indian scout. On reaching Custer’s abandoned encampment on the Republican River, ninety miles south of Fort Sedgwick. Lt. Lyman S. Kidder decided to move on to Fort Wallace. hoping to catch up with the main body of cavalry. Meanwhile. Custer and his men had arrived back at Fort Sedgwick.

When informed that he had missed Kidder’s small detachment. Custer decided immediately to backtrack the trail south in the hope of finding Kidder. On July 12, Custer’s column found the mutilated and partially burned and scalped bodies of Kidder and his men. There was evidence of a running battle. Only the Sioux scout Red Bead had not been mutilated. The massacre had been carried out by a large Sioux and Cheyenne war party about 10 days earlier. Custer ordered the men buried in a common grave on a hill above the ravine where the battle had taken place. Lt Kidder was twenty-one years old and a veteran of the Civil War. He was later reburied in St. Paul. Minnesota. Location: Sherman County Kansas. Leave Interstate 70 heading west. At Edson exit. turn right (north). west of Edson (first exit) then twelve miles north to battle-site. Monument and descriptive marker at site.

Beecher Island Battlefield 1868. The society of Cheyenne dog soldiers were credited with many acts of aggression against white settlers in Colorado and Kansas during the summer and fall of 1868. Under the leadership of Bull Bear, Tall Bull, White Horse and Roman Nose the Cheyenne warriors refused to give up their I way of life on the open plains and accept the confinement of a reservation. In an attempt to track down the dog soldiers General Philip Sheridan considered that a small party of frontiersmen and trained Indian fighters would have a greater chance of success rather than a slow and cumbersome army unit. On the 16th September 1868 a group of fifty frontiersmen from Fort Hays and Harker under the command of Major George A. ! Forsyth picked up the trail of a Cheyenne war party.

That evening the group camped on the .north bank of the Arikaree River: At some time durng the night the dog soldiers discovered the small group and on the morning of the 17th September a large Cheyenne war party under the leadership of Bull Bear, Tall Bull, White Horse and Roman Nose attacked Forsyth and his men. Forsyth immediately ordered his men to a small island in the dry riverbed of the Arikaree. The siege lasted seven days. Major Forsyth was wounded in both legs, Lieutenant Fredrick Beecher and five men were killed and fifteen men were seriously wounded. Between nine to twenty Cheyenne were killed and many more were seriously wounded. The death of War Chief Roman Nose was a significant loss to the Cheyenne. On the morning of the 25th September Lieutenant Colonel Louis H. Carpenter and a detachment of the 10th cavalry arrived at the Arikaree River to rescue Forsyth and his men. Location: Yuma County, Colorado. U.S.385 north towards Wray then U.S. 36 east towards St. Francis until a sign shows Beecher Island. Turn north on road, twelve miles to battlesite. Monument and markers.

Fort Steele 1868. Fort Steele was established on June 30th, 1868. The fort was named in honour of Colonel Fredrick Steele of the U.S. 20th infantry, a veteran of the Mexican and civil wars who had died in January 1868. The main function of the fort was to protect Union Pacific railroad workers from attack by warriors of the various Indian tribes whose hunting grounds were being destroyed by the construction of the railroad. During the Ute uprising of 1879, Fort Steele soldiers under the command of Major T. T. Thornburg responded to Indian agent Nathan Meeker’s request for aid. Major Thomburg was killed in action at the White River agency, Colorado. Location: Eleven mile north of Interstate 80, between Walcott Junction and Sinclair. Original blockhouse. Carbon County, Wyoming.

The Washita River Battlefield 1868. During the autumn of 1868 Chief Black Kettle established a camp on the banks of the Washita River forty miles east of the Antelope Hills in Indian Territory. At this same time General Philip Sheridan received orders from Washington to continue his initiative against the Southern Cheyenne and to extend his campaign into the winter months. Sheridan ordered Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer and the 7th cavalry stationed at Fort Larned into the field and to attack villages, peaceful or otherwise, found in the vicinity of the Antelope Hills. On the morning of the 27th November, 1868 the 7th cavalry attacked the peaceful village of Southern Cheyenne under the leadership of Black Kettle. Over one hundred and three Indians were killed, the majority of which were women and children. Black Kettle and his wife were killed in the attack.

It was the second time in four years that Black Kettle’s peaceful band had endured a massacre. During the attack the sound of gun fire alerted the Kiowa, Comanche and Arapaho villages located further down the Washita of the presence of the military. A large war party was formed and moved against Custer’s men as they were preparing to leave Black Kettle’s burning village. Major Joel Elliot and nineteen men were killed by the war party. Custer moved on to Camp Supply on the Canadian River to join General Sheridan and give the news of his victory. Location: Roger Mills County, Oklahoma. Leave U.S.283 at Cheyenne, then two miles west on U.S. 47A. The site is operated by the National Parks Service, Museum with Interpretative display and monument.

Fort Sill 1869. After the massacre of Black Kettle’s Southern Cheyenne on November 27. 1868 by Lt Colonel George A. Custer and the 7th Cavalry at the Washita River in western Oklahoma (Indian Territory). General Philip H. Sheridan deemed it necessary to have a strong hold for future actions against the plains Indians. Fort Sill was founded by Sheridan on January 8. 1869. The new military post was built in the heart of the Kiowa and Comanche country in southwestern Indian Territory. The post was built by the black units. the 9th and 10th Cavalry. who were later renamed “Buffalo Soldiers” by the lndians in reference to their short black curly hair which resembled the hairy coats of the buffalo. After the Red River War of 1874, many of the southern plains tribes surrendered at Fort Sill. Famous Comanche chief Quannah Parker remained with his people in the Fort Sill area after his surrender.

In later years, the cattle barons built a huge two-storey home for Quannah Parker. The chief was the main supporter for the leasing of Indian land during the 1880s and 1890s for the grazing of cattle. On October 7. 1894. famed Apache Geronimo and the exiled Apaches from the 1886 war in Arizona were transferred to Fort Sill. to continue their military captivity. Over the years. Geronimo and Naiche. the principal chief became a constant Source of interest and attraction to the white people who lived in and around the Fort Sill area. In 1905. Geronimo visited President Roosevelt in Washington to appeal against the military control over his people. and asked for liberty to be restored to the Apaches.

The request was turned down: feelings still remained high among the settlers of Arizona. even 19 years after the war. Geronimo died of pneumonia in a little stone house behind the Fort Sill hospital on February 17. 1909. Geronimo was buried in the Apache cemetery on Caches Creek outside the fort compound. Many famous Indian chiefs were also buried in the post Oak cemetery at Fort Sill: Quanah Parker, Satanta, Little Robe and Kicking Bird. Cynthia Ann Parker, the white mother of Quanah. is also buried at Fort Sill next to her son. Location: Comanche County, Oklahoma. Fort Sill military reservation is four miles north of the town of Lawton on US 277. The post is mostly intact and since 1911 has been the home of the US Army Field Artillery Centre and School.

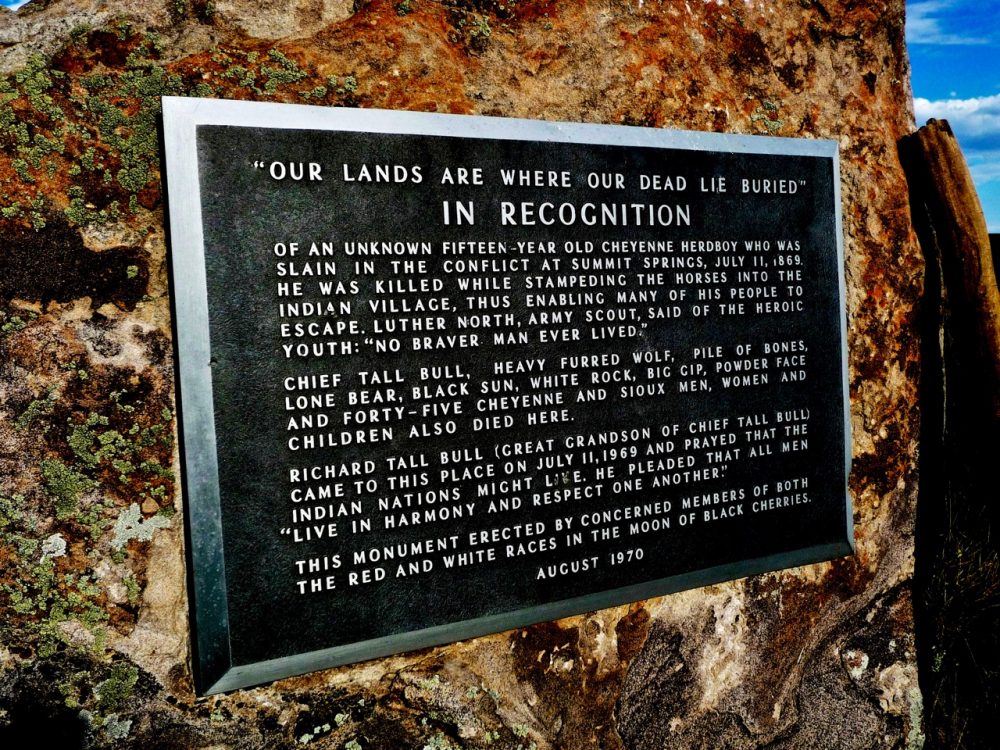

The Summit Springs Battlefield 1869. The destruction of Black Kettle’s village on the Washita River led to a quarrel between Peace Chief Little Robe and Cheyenne dog soldier War Chief Tall Bull. Little Robe blamed Tall Bull’s young warriors for initiating much of the trouble, between the whites and Indians. The two bands separated. Little Robe and his followers headed for Camp Supply and safety while Tall Bull and his warriors headed north to join the Northern Cheyenne in the Powder River country in eastern Montana. The victory at the Washita River also gave the U.S. army the necessary confidence to persist in its attempts to subdue the Southern Cheyenne of western Kansas and eastern Colorado. General Philip Sheridan ordered Major Eugene A. Carr and the 5th cavalry into the, field to search out and kill the Cheyenne dog: soldiers. After two skirmishes with Tall Bull and his warriors, Major Carr finally located the dog soldier camp at Summit Springs.

On the 10th July, 1869 Major Carr launched an attack on the unsuspecting village. Many warriors sacrificed their lives in the ensuing battle to enable the women and children to escape. Tall Bull, his wife and child and seventeen of his warriors took cover in a nearby ravine and kept up an intense fire against the soldiers for an hour. Eventually Major Frank North and his Pawnee Indian scouts stormed the ravine killing Tall Bull and all of his warriors. Tall Bull’s wife and child survived. Of the five hundred Indians camped at Summit Springs, fifty two were killed and one I hundred and seventeen taken prisoner. White Horse and some of the survivors continued north to join the Northern Cheyenne and their fight against the white man. Location: Logan-Washington County Line, Colorado. Ten miles south west of Atwood on unimproved road. Monument. Tall Bull’s tepee marked.

Fort Abraham Lincoln, 1873. Fort Lincoln cavalry post was established on the 3rd March, 1873. The infantry post a few miles to the north was established in the previous year. In the spring of 1873, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer and the 7th cavalry were transferred from Kentucky to Fort Lincoln. Custer was in command of the fort from the time of his transfer until his defeat and death at the Little Big Horn on the 25th June, 1876. From 1879 to 1882 soldiers from Fort Lincoln afforded protection to the construction workers of the Northern Pacific Railway who were working westwards from Bismarck. The last field engagement involving troops from Fort Lincoln was in December 1890 when soldiers were sent to patrol the area adjacent to the Cannonball River in anticipation of an uprising by Hunkpapa-Sioux ghost dancers from the Standing Rock reservation. Fort Abraham Lincoln was abandoned on the 22nd July, 1891. Location: Morton County. North Dakota. Four miles south west of Mandan on U.S.80. Interpretative display. Restored towers at infantry post. Three original buildings rebuilt at cavalry post, including Custer’s house. Monument and museum.

The Yellowstone Expedition 1873. In the summer of 1873 General Sherman ordered Colonel David S. Stanley with a command of fifteen hundred men to escort the Northern Pacific Railroad survey party of four hundred civilians west through the Yellowstone Valley. For more than twenty years the unseeded lands of the Yellowstone allowed the Sioux to live in their traditional manner and provided an abundant hunting ground. Prior to the Stanley expedition two survey parties passed through the Yellowstone in 1871 and 1872. The non-agency Sioux under the leadership of Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, Rain In The Face and Gall however, saw the Stanley expedition as a direct violation of the Fort Laramie treaty. Lieutenant Colonel George Custer and ten troops of the 7th cavalry were under the command of Colonel Stanley. Two skirmishes involving Custer and the 7th cavalry occurred on the north bank of the Yellowstone River on the 4th August and the 11th August, 1873. One soldier and two civilians were killed and four soldiers seriously wounded during these actions. Location: Yellowstone County, Montana. Pompeys Pillar, U.S. 10/312, Twenty-eight miles northeast of Billings. Historical landmark.

Massacre Canyon 1874. On the morning of the 5th August, 1873 a large Sioux war party under the leadership of Spotted Tail, Little Wound and Two ,Strikes encountered a band of Pawnee Indians who were returning home from their annual buffalo hunt. The hunt had been good and the Pawnee had in their possession over one thousand buffalo robes and much meat. The Sioux warriors numbering some seven hundred attacked the Pawnee encampment. Pawnee Chiefs Fighting Bear, Sun Chief and Sky Chief rallied their warriors to make a stand but the Sioux managed to chase the Pawnee for several miles. The timely intervention of the cavalry from Fort McPherson stopped I the battle. Twenty Pawnee warriors were killed during the early stages of the battle trying to protect the encampment.

Thirty-nine women and ten children were also killed. The Sioux lost between six to ten warriors. The effect of the massacre upon the Pawnee was devastating. The U.S. government had earlier offered to buy their I reservation and now the Pawnee chiefs accepted the offer. Within a matter of weeks the whole tribe was moved south to Indian Territory. The Sioux and Pawnee were traditional enemies and the Pawnee continued to serve as scouts for the army after the massacre. The famous Pawnee scouts first organised by Frank and Luther North in 1864 were instrumental in many V.S. army victories over the Sioux and Cheyenne. Location: Hitchcock County, Nebraska. Three miles east of Trenton on V.S.2S, original battle-site one mile south of monument. Descriptive marker.

Adobe Walls 1874. In the years 1872 to 1874 white buffalo hunters had pushed the northern Kansas buffalo herd to the point of extinction with over five million buffalo slain. During the treaty talks at Medicine Lodge in 1867 the U.S. government had promised to keep the white hunters off Indian buffalo grounds but as the northern herd diminished hunters moved south into the Texas Panhandle. Led by Billy Dixon, Bat Masterton and Jim Hanrahan twenty-nine buffalo hunters set up a camp at Adobe Walls. Angered by the violation of their treaty rights and the U.S. army’s active encouragement of the buffalo hunters the Indians decided to strike back. On the 26th June, 1874 a large war party of seven hundred Comanche, Southern Cheyenne and Kiowa under the leadership of Quanah Parker and medicine man Isa-tai attacked Adobe Walls near the South Canadian River Isa-tai, the Comanche medicine man, had for-seen victory at Adobe Walls with the use of a magical paint that would protect the warriors from bullets.

The battle lasted three days. Quanah Parker led many of the frontal assaults on the trading post but the hunters were able to maintain their position with the aid of Sharp rifles I’ equipped with telescopic sights. During one of the charges Quanah Parker had his horse shot from beneath him and so took cover behind a dead buffalo. Almost immediately Parker was hit in the back by a bullet that had ricocheted. This incident signalled the end of the battle with the warriors retreating under the belief that the whites had some strange new magic. Isa-tai was held responsible for the defeat. Thirteen Indians were killed in the battle but it has been suggested that bodies may have been removed during the action. Three buffalo hunters were killed. Location: San Patricio County, Texas. Twelve miles north east of Stinnett on U.S.136/U.S.207. Sign posted then seventeen miles east (nine miles paved). Monument and grave markers. Private land.

Black Hills Expedition 1874. The Fort Larimie Treatv of 1868 granted formal ownership of the Bighorn country, the Powder River country and the Black Hills of South Dakota to the Sioux nation. The Black Hills region covered an area of approximately fifty square miles and was rich with gold and mineral deposits. The Sioux enjoyed the freedom of their large domain in relative peace for six years until rumours of mineral wealth in the Black Hills reached eastern newspapers. Under increasing pressure from miners and settlers the United States government ordered a survey of the Black Hills. In July 1874 Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer with a command of 951 men including soldiers, engineers, scientists and teamsters set out for the Black Hills. The expedition lasted two months and covered some 1,205 miles. News of gold discoveries spread quickly and Sioux lands were overwhelmed by miners and settlers. Location: Custer County, South Dakota. Two miles east of Custer on U.S. 16A. Custer’s campsite at French Creek, Monument. Private Land.

Palo Duro Canyon 1874. The battle of Adobe Walls marked the beginning of the Red River Buffalo war of 1874-1875. The Plains Confederacy of Cheyenne, Kiowa and Comanche launched wide ranging attacks on whites from Colorado to Texas.. The United States government ordered all Indians to return to the reservations by the 3rd August, 1874 or face the consequences of being engaged in battle with the U.S. army. The Plains Confederacy rejected the ultimatum and so Washington sent five columns of cavalry into the field under the command of Colonel Nelson A. Miles, Colonel Ranald Mackenzie, Colonel George P. Buell, Lieutenant Colonel John W. Davidson and Major William Price. Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie with eight companies of the 4th cavalry was ordered to seek out and destroy the village of Comanche War Chief Quanah Parker and in doing so break the heart of hard core Indian resistance.

At dawn on the 28th September, 1874 Mackenzie’s Seminole Negro scouts located a large village on the floor of the Palo Duro Canyon. Mackenzie and his soldiers followed a narrow trail that switch-backed to the canyon floor nine hundred feet below. Mackenzie led one charge into the village with soldiers setting fire to the lodges. Three Indians were killed during the battle, the most prominent being Kiowa War Chief Red Warbonnet. Mackenzie captured over fourteen hundred Indian horses and then ordered them to be shot. An Indian without a horse was not considered a threat. Quanah Parker and his followers were not present during the attack. Parker and his band of Kwahadie Comanche eventually surrendered at Fort Still on the 2nd June,1875. Location: Park entrance is twelve miles east of Canyon on U.S.217 then five miles south. Descriptive marker ten miles from park entrance. Actual battlesite on private land.

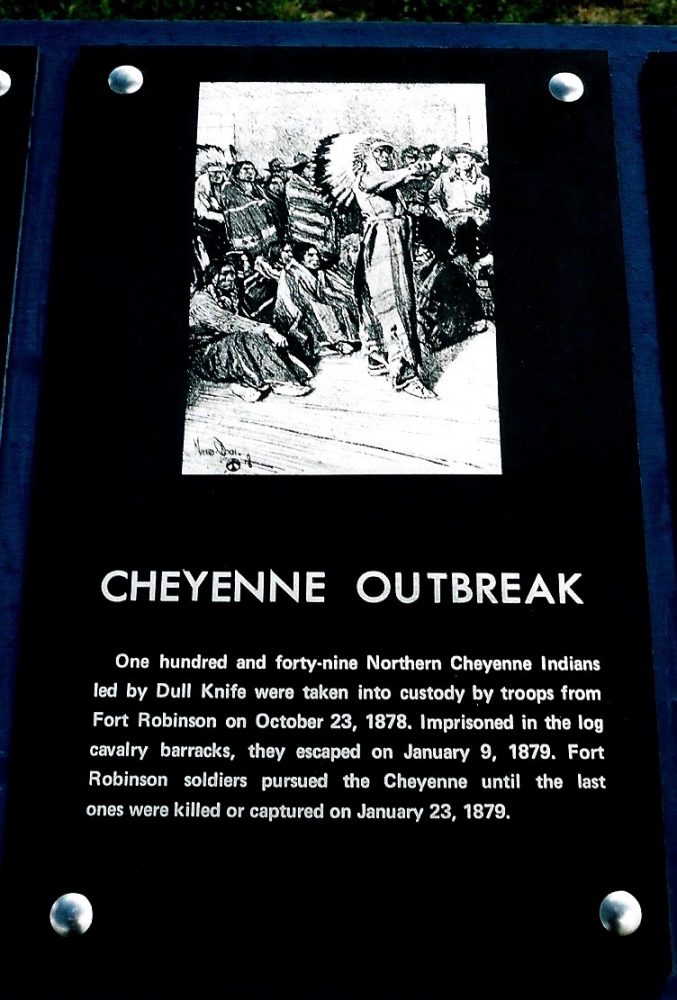

Fort Robinson 1874. The treaty of 1868 signed by Red Cloud, numerous Sioux chiefs and U.S. government peace commissioners guaranteed the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne food and supplies in exchange for large area of land. During the summer of 1873 Red Cloud, Old and Young Man Afraid I of His Horses and their followers moved to an agency near the White River in northwestern Nebraska. Frequent skirmishes occurred at the new agency between white employees and warriors from the Northern Sioux bands who were not yet willing to accept the confinement of a reservation. At the request of Indian agent JJ. Saville, Major Baker in command of a military expedition visiting the various I agencies ordered four companies of infantry and one cavalry unit to remain at the agency to act as a deterrent against further hostilities.

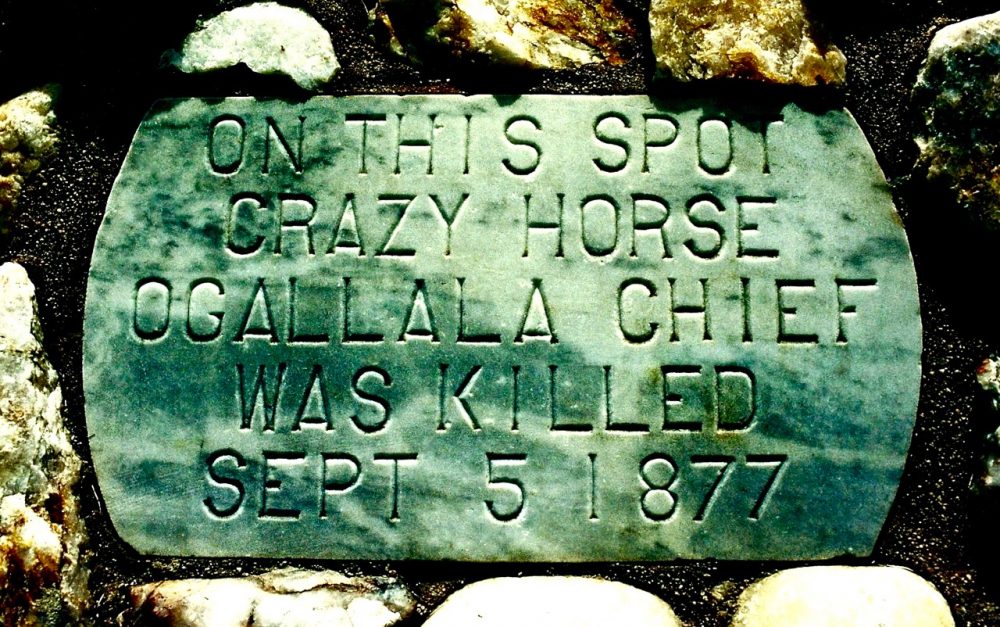

The camp set up by these soldiers on the 29th March, 1874 was named Camp Robinson in honour of Lieutenant Levi Robinson who had recently been killed by a Sioux war party. Captain W.H. Jordan arrived at Camp Robinson in June 1874 and almost immediately issued orders to his troops to begin construction work on new barracks and officers quarters. In January 1878 the U.S. army ordered a name change for the camp to Fort Robinson. One of the major events to take place at Fort Robinson was the surrender of Oglala Sioux War Chief Crazy Horse on the 6th May, 1877. Crazy Horse was murdered at the fort four months after his surrender. Location: Dawes County, Nebraska. Three miles west of Crawford on U.S.20. Monuments restored buildings and museum. Operated by National Park Service.

The Sappa Creek Massacre 1875. In mid-April 1875 word reached Fort Wallace in western Kansas that a band of Cheyenne had left the reservation in Indian Territory, and were heading north to Montana to join their relatives, the Northern Cheyenne. On 19 April, Second Lieutenant Austin Henely with forty soldiers of H Company, of the Sixth Cavalry left Fort Wallace to pursue the fleeing Cheyenne. Henely and his troops encountered a party of buffalo hunters who informed them that the Cheyenne were camped seventeen miles away on the north fork of the Sappa Creek. In the early hours of April 23, 1875 Henely, his men and around twenty civilian buffalo hunters attacked the village. On first appraisal the village appeared to be comprised of twelve lodges, which would have housed approximately sixty people.

However, a number of sleeping holes were cut into the bank below the semi-circle of the bluffs to accommodate the destitute Black Horse and Sand Hill people. Cheyenne oral history places at least one hundred people in the village. In the three hour battle Henely injudiciously divided his command so that only twenty to thirty soldiers took actual part in the battle. The official report stated twenty-seven Cheyenne killed, nineteen warriors and eight women and children. Henely took no prisoners and killed more Cheyenne than the combined army columns (5,000 soldiers) had during the six month winter campaign of 1874-1875. Cheyenne oral history and reports from local civilians living in the area put the Cheyenne dead at between seventy to eighty dead. Two soldiers were killed during the battle. Eight soldiers were later awarded Medal’s of Honour for their actions at Sappa Creek.

The Powder River Battlefield 1876. As the non-reservation Sioux and Northern Cheyenne ignored the January 31st 1876 ultimatum to return to the reservations, General Philip Sheridan received authority from Washington to proceed with military action against the Indians living in and around the Powder River country in eastern Montana. In early March 1876 a column of eight hundred and eighty three men including scouts, herder’s and packers under the command of Colonel Joseph]. Reynolds left Fort Fetterman for the Powder River. General George Crook accompanied this expedition in the capacity of military observer. Soon after the start of their march the column of soldiers was spotted by Indian scouts. Colonel Reynolds and three hundred men followed the scouts trail hoping to locate an Indian .village. At dawn on the 17th March, 1876 army scout Frank Grouard located the Sioux and Cheyenne village of Two Moons and He Dog containing sixty five lodges.

Reynolds plan of attack was simple, he split his command into two units with one to charge the village from the north and one to charge from the south. Reynolds upper hand lay in the element of surprise but very quickly the Indians staged a remarkable turnaround forcing the soldiers to retreat. Reynolds was left with no option but to burn the captured village. Two Indian warriors were killed in the attack but many women and children later died from wounds inflicted during the attack. After the. attack Colonel Reynolds faced a court-martial for leaving a wounded man in the field. Reynolds was suspended from rank and command for one year. President Grant remitted the sentence due to Reynolds distinguished service in the Civil War. Location: Thirty miles south from the town of Broadus, on unimproved road. Monument. Private land.

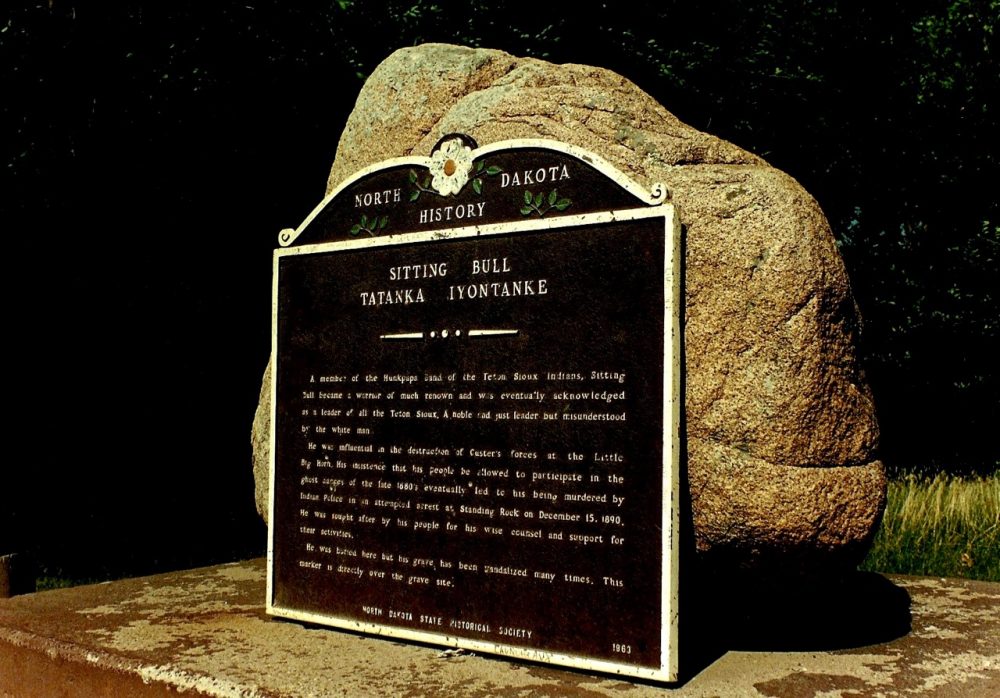

Deer Medicine Rocks Montana Territory 1876. In 1874 Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer and the Seventh Cavalry discovered gold in the Black Hills of South Dakota, the sacred dwelling place of spirits for the Lakota nation. Despite the area being closed to white settlement hordes of gold miners flocked into the Black Hills. An attempted offer to buy the area by the United States government was refused. As a consequence President Grant instructed the War Department to issue an ultimatum ordering all Indians living in unseeded lands to return to the reservations by the 31 of January, 1876 or face military action. The non-agency Lakota led by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse rejected the ultimatum. Principal Chief of the non-agency Lakota Sitting Bull sent messengers to every camp on and off the reservation to meet on Rosebud Creek to participate in a Sun Dance. Ten to twelve thousand Indian’s responded to Sitting Bull’s call.