They say that time flies although it is nice to look back at milestones in ones creative endeavours that has huge flagpoles in the sand. This year sees the twenty-fifth anniversary of the publishing of my twenty-four page booklet with co-author Kim Vaughan that tells the story of what really happened to the Cheyenne at the Sappa Creek in late April, 1875. My story started way back in early June, 1990 when I was driving through northwest Kansas. I was on my way to attend the Fort Phil Kearny/Bozeman Trail Days in Sheridan, Wyoming. I was also carrying copies of my 1980’s battlefields photographic prints to give to Mary Ellen MacWilliams who one of the founding members of the Fort Phil Kearny Bozeman Trail Days Association as a donation to the association. Prior to leaving Sydney Australia my wife Kim Vaughan and co-author on the “Battlefields, Monuments and Markers” book had mentioned that it would be interesting if I was able to locate the Sappa Creek Massacre Site as we had tried to locate it during our 1987 and 1989 road trips on the Great Plains with no luck. We had been interested in what had happened to the fleeing Southern Cheyenne at the end of the Red River War 1874-1875 for close to three years since we first published “Battlefields, Monuments and Markers” in 1987.

The accounts on what happened during this particular engagement were not recorded in the main history books about the Cheyenne and their fight to retain their culture and way of life as Americans moved west into their lands. At that time there was no plans to publish a second edition of the battlefields book and I actually thought my work regarding this interesting period of the Southern Great Plains Indian Wars was at a end. This was one of the reasons I had decided to donate copies of my photographs so there would be a record of my research in the 1980’s. And this road trip in the summer season of 1990 was more of a holiday and a chance to catch up with fellow writers and historians while attending the events in Wyoming. (Pictured below is co-author Kim Vaughan walking across the Sappa Creek Village Site when we visited Larry Catlin’s Ranch in 1992).

As I continued my drive through Kansas during my 1990 road trip I stopped at a rest area and to my surprise they had a bronze historical marker above the roof of the sheltered area. I looked closely at the marker and found that they had Sappa Creek located on the map. I quickly brought out my road map and reckoned I was only a county or two away from the original site. I decided to investigate the following day and stopped at the Last Indian Raid Museum in Oberlin. I was informed by Sandy Russell the museum curator that I should travel west to the town of Atwood and ask at the local museum if they knew about the Sappa Creek. When I arrived in Atwood I went into the museum and the curator Natilie Mickey said she did not know where the Sappa Creek Massacre Site was located. I purchased a red covered old typewriter booklet by two historians William D. Street and E. S. Sutton.

As I was leaving the museum a young lady walked through the front doors of the museum and Natilie asked if she knew about the location of the Sappa Creek Massacre Site. To my surprise she said that the site was located ten miles straight south on the Larry Catlin Ranch. The young lady now lived in California and was home visiting her parents on her summer vacation. She said that she remembered her parents talking about what happened to the Cheyenne at Sappa Creek when she was a young child. This was indeed a lucky break and I thanked her for this important information. I did not know it at that time but the red booklet would yield up secrets that Kim and I were able to use in our future research. (Pictured below is the Cheyenne/Arapaho Annual Powwow at Colony, Oklahoma during the 1992 road trip after we had published our booklet).

When I arrived at Larry Catlin’s Ranch after the short ten mile drive I asked Larry if it would be possible to walk around the village site and take some photographs. he said that would be okay and I spent the next two hours exploring the site. Larry told me the stories that he knew and also that sometimes when he and his family were sleeping they would be awakened by the sounds of crying and screaming from the valley floor where the twelve lodges of Cheyenne was located that fateful day in 1875. Some may say that this was indeed creepy although I always respected what the local rancher had to say about what took place on their property. I thanked Larry for his kindness in letting me look around and made my way north to Sheridan, Wyoming for the opening of the Fort Phil Kearny/ Bozeman Trail Days. I enjoyed the four day event and met Raymond J. DeMallie, Joseph Porter, Doug Ellison and Jack D. McDermott who were highly respected writers on the Sioux Wars of the 1854-1890 period. Jack was interested in my recent Sappa Creek find in Kansas and he had worked under the Ronald Regan Administration for the National Park Service and the Council on Historic Preservation.

Jack said to keep him informed if I intended to publish something on the Sappa Creek Massacre in the years ahead. Up until this time there was no written material on the true happenings at Sappa Creek apart from the chapter “Sappa Meaning Black” by renowned Nebraskan author Mari Sandoz that was published in her book “Cheyenne Autumn” in 1953. At this time I was just happy to have located the site and only planned a short text with images in a future second edition of “Battlefields, Monuments and Markers.” (Pictured below is my first of two visits with western author Caroline Sandoz Pifer at her Sands Hills home in northwestern Nebraska after publishing Cheyenne Hole in 1992).

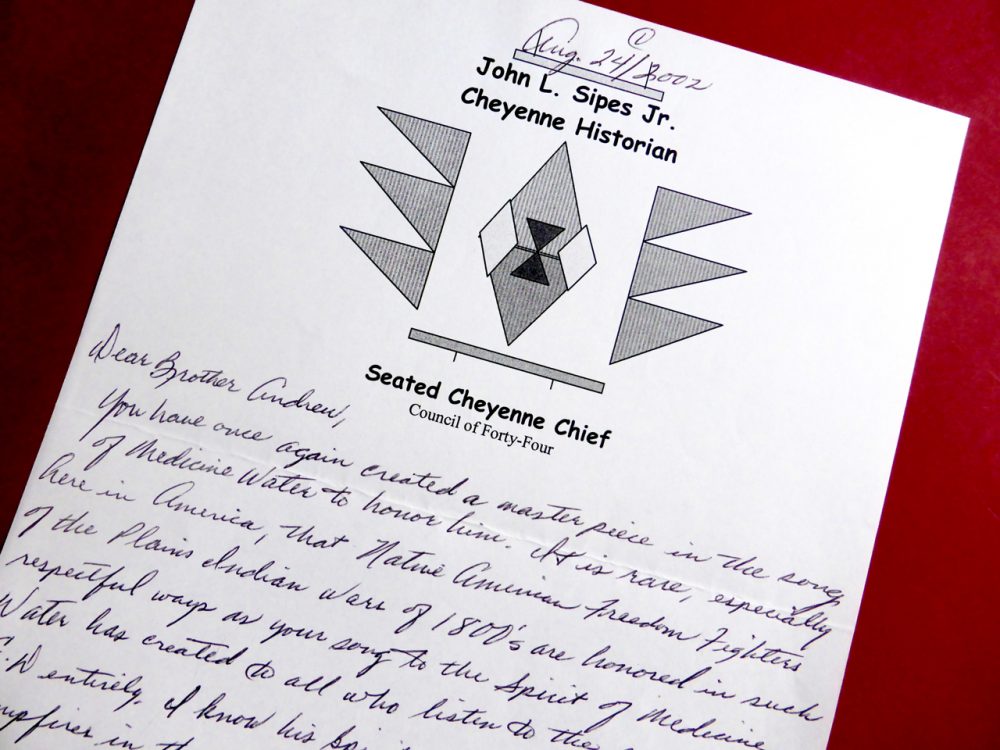

When I returned back to Sydney, Australia I found myself engrossed in the information that writers Street and Sutton had recorded in their booklet that the museum in Atwood had printed up for sale to interested parties who visited the museum. I wrote to the National Archives in Washington D. C. and asked if they had copies of Lt. Austin Henley’s Official Report on the Sappa Creek engagement. A few weeks later a detailed photocopied report arrived in Sydney. I also wrote to Mari Sandoz’s sister Caroline at her Sand Hills home in Nebraska and she was kind enough to reply with information that she remembered from conversations with her sister about the massacre. And by sheer chance when I phoned the Oklahoma Historical Society in Oklahoma City the phone was answered by John Sipes Jr who was the Cheyenne Tribal Historian. John had been recording important Cheyenne historical sites for over two decades and he was able to pass on information about the oral history regarding the massacre that was passed down to him by Pete Birdchief 1899-1986. Birdchief was the previous Cheyenne Tribal Historian and he knew many of the survivors from that dreadful day on the Sappa Creek.

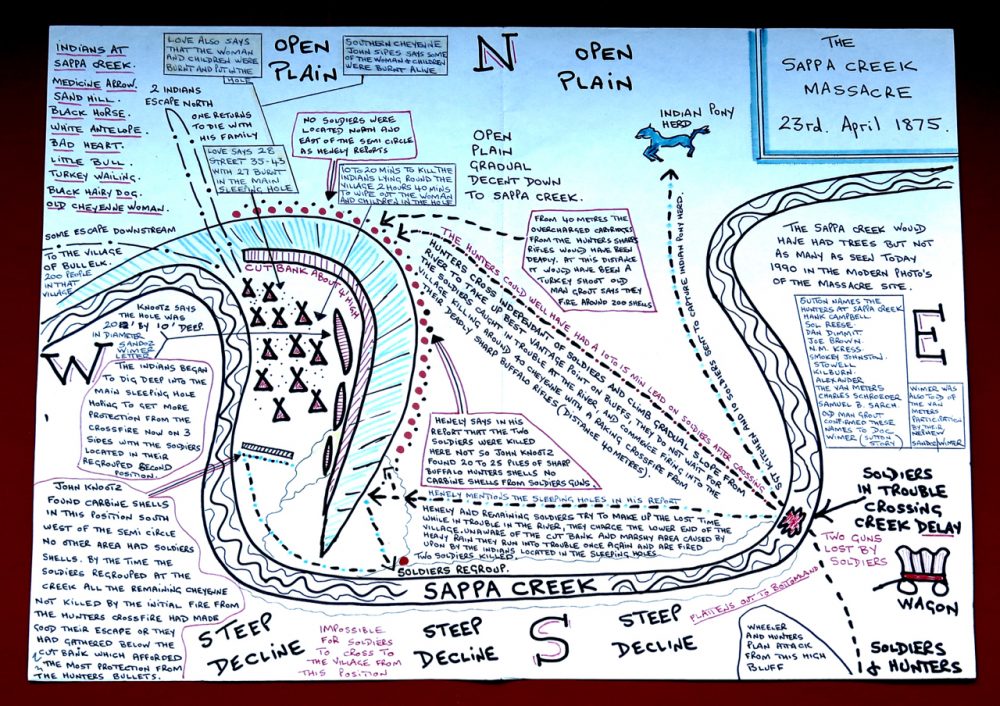

For the next twelve months when we had spare time from our daily jobs Kim and I wrote down our case for a cover-up and what really happened to the Cheyenne who were camped at Sappa Creek on that fateful day on the 23rd of April, 1875. It was like putting together a case that would be represented in court. We wrote up fifteen hundred words and we had thirty-four references to back up our case for a cover-up and that it was the buffalo hunters who inflicted most of the death and destruction brought to bare on the innocent women and children who lost their lives as they tried to flee the carnage on the valley floor. (Pictured below is the hand drawn map I put together for the Sappa Creek Massacre. Later I would have this map reproduced by computer graphics expert Graham Carney and it would be published in the twenty-four page booklet).

When all our information about the Sappa Creek Massacre was compiled I sat down and did a hand drawn map of the events that took place during this mysterious engagement. Was there really twenty plus civilian buffalo hunters located on the rims above the village site. And if so this would explain why the United States Military would want to keep this information from leaking out back east to all those people who felt that Cheyenne women and children were being targeted in a unauthorised military engagement that involved civilians. Lt Austin Henley could not control the hunters once the firing had started and in the end a cover-up was always going to be the final outcome. Maybe this is why the Oklahoma University Press published books on the Great Plains Indian Wars did not have any fruitful material on what happened at Sappa Creek. It is funny how a cover-up can make its way through the decades and still keep interested parties in the dark.

The Cheyenne knew what happened at Sappa Creek and it always seems strange that noted historians never ask what they know about certain incidents in their history when working on a book project. They would much rather keep recycling the old tried and trusted military reports housed in the nations capital and swear blind that this is how things really panned out. Personally I have always enjoyed talking with the people who live on the land and what they have to say with their interesting take on the oral history passed down the generations from their parents and grandparents. This coupled with the information from the likes of local historians like William D. Street, E.S. Sutton and Mari Sandoz who spoke with the last generation of Indian war survivors makes for a more compelling read and not the feathering of ones yearly salary when writing a book for the university establishment without collaborating with the Native American Nations involved in particular encounters that gave us the so called wild west.

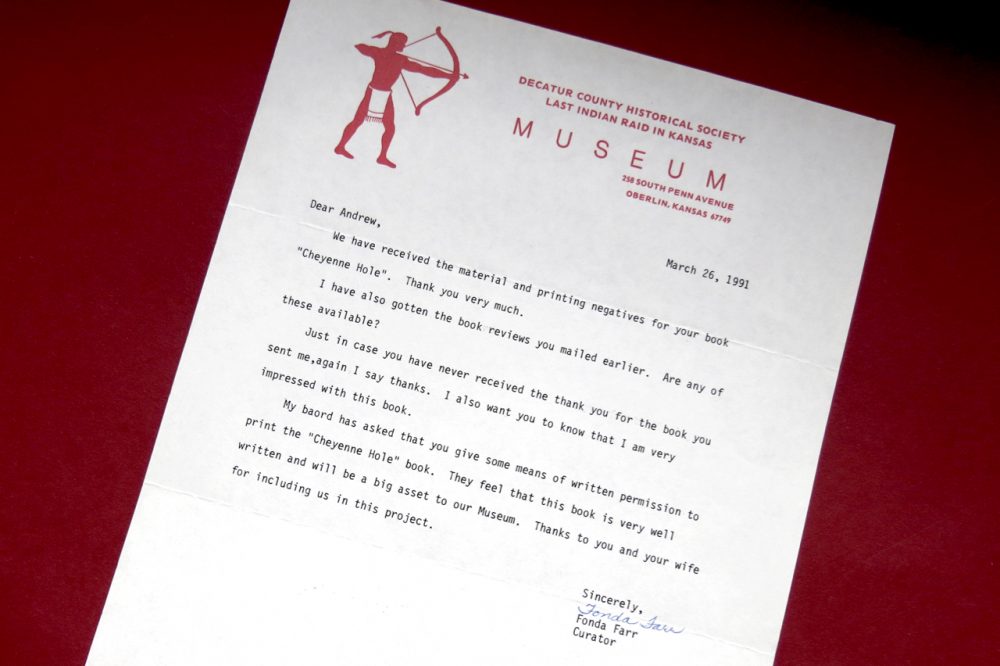

After the twenty-four page booklet was published in 1991 I sent a copy to Sandy Russell and Fonda Farr the curators at the Last Indian Raid Museum in Oberlin, Kansas. A few months later I received a letter asking permission for the museum to print up the booklet for sale to interested parties who visited the local area and who were students of the Great Plains Indian Wars period of the mid to late nineteenth century. This was indeed a honour as the locals are always the hardest to win over when a outsider comes to town as they say in the western movies. I copied a second set of printing negatives and posted them over to Kansas. The museum printed up a short print run of five hundred copies and I am sure that twenty-five years later they are long sold out. I posted copies of the booklet to Caroline Sandoz Pifer and thanked her for her help and friendship during our exchange of letters while Kim and I were working on the Cheyenne Hole booklet.

When travelling the Great Plains in 1992 and again in 1999 Kim and I stopped in at Caroline’s Sand Hills home in northwestern Nebraska and enjoyed sharing stories about her life as part of the Jules Sandoz family over weenie sandwiches and hot mugs of tea. Caroline lived until the ripe old age of one hundred and one years and passed away on the 12th of March, 2012 while residing in a Gordon Nursing Home. Caroline was a prolific author after obtaining her degree at university at the age of seventy-one years old. And I am sure her famous sister Mari Sandoz would have been extremely proud of her younger siblings accomplishments with the pen and the typewriter keys. And the great work she did with Mari’s letters and over 4,000 index cards relating to Mari’s extensive work on the Great Plains.

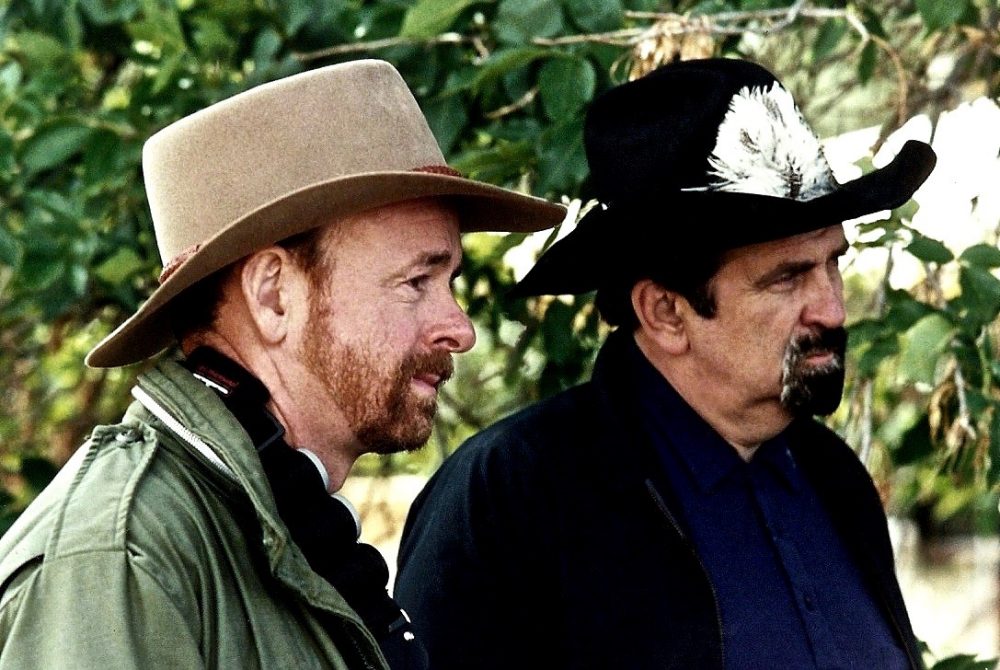

When I was on my Great Plains book selling trip in 1995 I bumped into Jack McDermott and his partner author Margot Liberty at the Custer Battlefield Trading Post in southeastern Montana. I had posted Jack a copy of the Cheyenne Hole booklet shortly after it was published in Sydney, Australia in 1991. Over coffee on the trading porch Jack said that he was extremely pleased with the efforts of Kim and myself in putting together a strong case for a military cover-up at Sappa Creek. He continued by saying that it is material like ours that is sadly missing when one tries to put a balanced view of the Indian Wars from 1854-1890. As I departed he said give Kim his best regards for a job well done. The kind positive comments by Jack McDermott may not be money in the bank although they are like gold nuggets in the palm of ones hands when coming from such a well respected historian and fellow writer/artist. (Pictured below is Writer/Historians Joseph Porter (Left) and Jack McDermott (Right) at the Rosebud Battlefield in Montana during the 1990 Fort Phil Kearny/Bozeman Trail Days).

After the Cheyenne Hole booklet was published I continued to keep in touch with John Sipes Jr the Cheyenne Tribal Historian through letters and phone calls. When I was on the Great Plains in 1996 selling my four books Kim and I travelled to to Norman, Oklahoma to stay with John his wife Dee Bigfoot and their children. It was a interesting weekend and we talked all things Cheyenne and John was keen to speak about the life of his great great grandfather Medicine Water and his warrior wife Mochi (Buffalo Calf Woman) who had survived the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864 and fought by her husbands side during the Red River War. Like the information available on the Sappa Creek Massacre there was next to nothing recorded in the history books regarding the life and times of Cheyenne War Chief Medicine Water who led his Bowstring Warriors against the United States Cavalry during the war.

The only material that focussed on the deeds of Medicine Water and Mochi was the deadly attack on the emigrant German family in central Kansas at the start of the Red River War. The fact that these people were still human and they were only trying to protect their families and way of life meant nothing to the war mongers back east in Washington. John and I trade personal gifts before Kim and I departed back to Los Angeles and I thanked him for inviting the both of us to the Peace Chief Naming Ceremony of his uncle Tulane Wilson while we attended the Cheyenne/Arapaho Annual Colony Powwow. Before we set out I gave John a hundred copies of “Cheyenne Hole” as a gift for his collaboration on the project in 1991. We agreed to keep in touch and follow up a project idea on a movie about the life and times of Medicine Water.

John and I continued to keep in touch after Kim and I arrived back home in Sydney in August, 1996. My book publishing days were now done and dusted and I had moved into colour photographic exhibitions that included wall text of Jack Little’s “Lakota Spirit” booklet along with other quotations that suited the image content. When I finished selecting powwow images for my Powwow: Native American Celebration 1984-1999 exhibit I included one of the images I had created with John while staying at his Norman, Oklahoma home in 1996. When the collection was selected for a three year national tour of the United States of America by Missouri based Non For-Profit Touring Company Exhibits USA it was a thrill for myself and all the dancers I had photographed over the years.

John continued to log and record sacred sites of the Cheyenne and write newspaper articles that informed the Cheyenne people of their recent past. Although many of the elders knew what John was on about as they had been his greatest resource for information. In 2000 John was giving the highest honour by his Cheyenne Nation when he was made a Peace Chief in the Council of Forty-Four. John and I continued to keep in touch through phone calls and letters and together we built up interesting material regarding Cheyenne history and most importantly the life of his great great grandfather Medicine Water. Sadly John passed away at age fifty-seven in 2007 and we never got the opportunity to complete our screenplay about his grandfather. Although when writing two extra songs with musician Chris Fisher for the 2000 Great Plains album I decided that my song would be about the life and times of Medicine Water. When the album was pressed for the second time with the two new songs included I also dedicated the album to Medicine Water and his life journey.

John later wrote a lovely letter thanking Chris and myself for honouring his grandfather with our song and also about our work on the album generally. And what started out as a cold phone call in early 1991 to the Oklahoma Historical Society ended up with a sixteen year friendship that will always remain special in my heart. Scottish people much like Native Americans suffered at the hands of their oppressors in recent times but one thing we certainly had in common was our black humour and having a good old belly laugh about all things the system of control said we should be like in this earthly life. There was many times over the years when John and I would laugh out loud across the telephone wires as like-minded souls and good brother friends should always try to do when in contact with each other.

During many visits with Native American elders and ranchers over the decades of my Great Plains road trips I have enjoyed listening to many stories passed down the generations by family members. This particular style of communication is not always taken serious by the academic who tends to see things more in black and white and most importantly written down on paper and if possible signed by the individuals giving their particular viewpoints on a battle or engagement on their lands or by a relative who witnessed the event or was told about it as a young child by their parents or grandparents. If one of my many conversations over the years sticks in my head it would be the visit to Larry Catlin’s ranch in 1990. Over a hot cup of tea I was told the story by Larry of how when sometimes working in his sheds late at night that he hears the sounds of screaming and crying coming from the Sappa Creek valley floor. If I have one lasting memory of my Great Plains travels then this would certainly be the one that has left a lasting impression.

There is no monument located on Larry Catlin’s ranch to mark what happened here in late April, 1875. And I guess Larry still has times late at night when working in his shed that the screams and crying filter up from the old Cheyenne village site. During my road trip from Oklahoma City up to Montana in 2010 I stopped at Sappa Creek and asked Larry if I could walk down to the village site and tie some sacred coloured cloth on the tree at the edge of the site. It is not a monument although it was my way of remembering the fallen Cheyenne women and children who lost their lives on that fateful day. And today we now have a robust internet and information at our fingertips I am pleased to have the Cheyenne Hole: The Story of the Sappa Creek Massacre, 23rd, April, 1875 available for downloading on my website. I suppose this is my way of remembering history as it really happened. ( Pictured below is one of the photographs that I created with John at his Norman home in 1996).