Sappa Creek Meaning Black: When I visited the Sappa Creek Massacre Site located on the Larry Catlin ranch twelve miles south of the town of Atwood in northwestern Kansas in June, 1990, I asked Larry who was the gentleman that tied the white prayer cloth to the old tree on the valley floor. This is where the twelve Cheyenne lodges had been located on the 23rd of April, 1875 when the soldiers and buffalo hunters attacked the small village. Larry said a Cheyenne Indian from Oklahoma City had visited his ranch a few months earlier asking to have a look around. When I returned to Sydney later that year I made a phone call to the Oklahoma Historical Society hoping to get some information regarding the history of the Cheyenne during this turbulent period in their recent history. The gentleman who picked up the phone at the other end was extremely polite and helpful and he informed me that his name was John Sipes and that he was the current Cheyenne Tribal Historian. John informed me that this particular encounter at Sappa Creek in Kansas was remembered in Cheyenne oral history as the time the woman, children and babies were thrown into the fires of the burning tepees by the soldiers. I spoke with John on a number of occasions over the next nine months by phone as my research into the massacre unfolded and gathered pace. And finally on the 6th of November, 1991 I published a twenty-four page booklet with co-author Kim Vaughan that had thirty-three references to back up our case of a cover-up by Lt. Austin Henely the officer in charge at Sappa Creek and his illegal use of over twenty-two buffalo hunters in the action against the Cheyenne. Pictured below is the Sappa Creek Massacre Site in northwestern Kansas. I shot this image during my initial visit to the site in 1990.

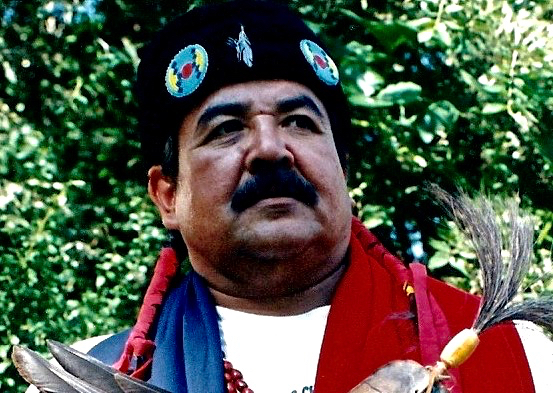

Medicine Water & Mo-chi Buffalo Calf Woman: I kept in touch with John after the publishing of Cheyenne Hole in 1991. We exchanged letters and continued our long distance phone conversations talking about all things Cheyenne. And after my book selling trips across the Great Plains in 1995 and 1996 we finally caught up in person when John and his wife Dee Bigfoot along with their children attended the opening night of my Native Lands: The West of the American Indian photographic exhibition on the 3rd of August, 1996 at the Wyoming Pioneer Memorial Museum in Douglas, Wyoming. Kim and I were shortly heading down to the Southern Great Plains for a holiday and John and Dee invited us to stop and attend the Cheyenne/Arapaho Powwow at the tribal grounds in Colony in western Oklahoma on the 2nd and 3rd of September. We had attended the Colony Powwow on our own in 1992 and we both looked forward to joining John and his family at the annual event in 1996. The powwow was interesting and the people were extremely kind and polite to their visitors from Australia. John introduced Kim and I to his uncle Tulane Wilson and his with Janine and we both witnessed the Peace Chief Naming Ceremony for Tulane at John’s camp. When the weekend events were over Kim and I returned back to stay at John and Dee’s home in Norman, Oklahoma. And over afternoon tea and coffee John spoke about his great great grandparents Mo-chi and Medicine Water. John and Dee’s living room was filled with photographs of his relatives and he spoke passionately and fondly about their lives. Pictured below is the Sand Creek Massacre Site in southwestern Colorado. I shot this image in 2013 when Kim and I were travelling around the area. Pictured below is John Sipes at his home in Norman Oklahoma. I shot this images of John during my weekend stay at his home in 1996.

Sand Creek & Washita River Massacres: John said that his great great grandmother Mo-chi (Buffalo Calf Woman) had somehow survived the massacre at Sand Creek in Colorado Territory when Colonel John Milton Chivington and his soldiers had attacked Black Kettle’s Cheyenne village on the 29th of November, 1864 and massacred around one hundred and thirty Cheyenne of all ages. Mo-chi was twenty-three year old woman at the time as she witnessed her husband Standing Bull and also her father being gunned down by the soldiers. And by the time of the Washita River attack in western Oklahoma (Indian Territory) four years later Mo-chi had married Cheyenne Bowstring Society Warrior Medicine Water and they had three young daughters all aged under five years old. This village was the remnants of Black Kettle people and the old peace chief must have thought he was reliving Sand Creek all over again as he watched his people being gunned down in the snow. This time around Black Kettle would not escape the slaughter and he and his wife were killed during the engagement with George Armstrong Custer’s Seventh Cavalry as they tried to cross the Washita River and safety on the other side. As for Mo-chi and Medicine Water they somehow managed to avoid the rain of bullets flying in and around the fifty Cheyenne lodges. And as they tried to cross the river to safety their oldest child Measure Woman was hit by a soldiers bullet. Pictured below is the Sand Creek Massacre Site in southeastern Colorado. I shot this image during my third visit to the site in 2013.

Escaping The Washita River Massacre: Over dinner on the Sunday evening I asked John about his grandparents escape with three young children in tow. He said that family oral history says that Red Bird a young warrior friend of Medicine Water helped to protect his friend and his family as they tried to cross the Washita River. Red Bird had managed to rescue his war horse at the outset of the attack and with it by his side he kept firing his rifle at the soldiers as Medicine Water and Mo-chi and their young children made their getaway. Eventually a soldiers bullet brought down Red Bird. Medicine Water seeing his friend fall turned his horse around and raced to the dead Cheyenne. Red Bird’s war horse was still standing next to its owner and Medicine Water shot the horse dead before returning back across the river to his family. This was a Cheyenne custom so that a warrior and his favourite mount could be together in the spirit world. After surviving both the Sand Creek and now the Washita River Massacres Mo-chi vowed never to be in a position of vulnerability again. Mo-chi would become a woman warrior and fight by Medicine Water’s side in their quest to defeat the soldiers and settlers who were invading Cheyenne lands. Pictured below is the Washita River Battlefield in western Oklahoma. I shot this image during my visit to the site in 2010.

Cheyenne Oral History & Storytelling: I was thrilled by the depth and detail of John’s storytelling and he informed me that for over two decades he had tramped the areas in western Oklahoma, Kansas and eastern Colorado recording Cheyenne historical sites. John said that he had filled twenty file cabinets with paperwork and they were lodged at the Oklahoma Historical Society for security reasons. John continued his storytelling after dinner on the Sunday evening and said that for the next six years after their close shave with death at the Washita River that Medicine Water, Mo-chi and the children managed to stay out of the reach of the United States Army who continued to search the areas of western Oklahoma for the free roaming bands of Cheyenne, Kiowa, Plains Apache and Comanche. The American Government had decided that one way to bring these hostile bands to bay was by slaughtering the huge Southern Great Plains buffalo herd. General Phillip H. Sheridan in Washington D.C. gave the okay for large groups of buffalo hunters with their deadly Sharp rifles to kill off the herds and this would deprive the Indians of their main food source.

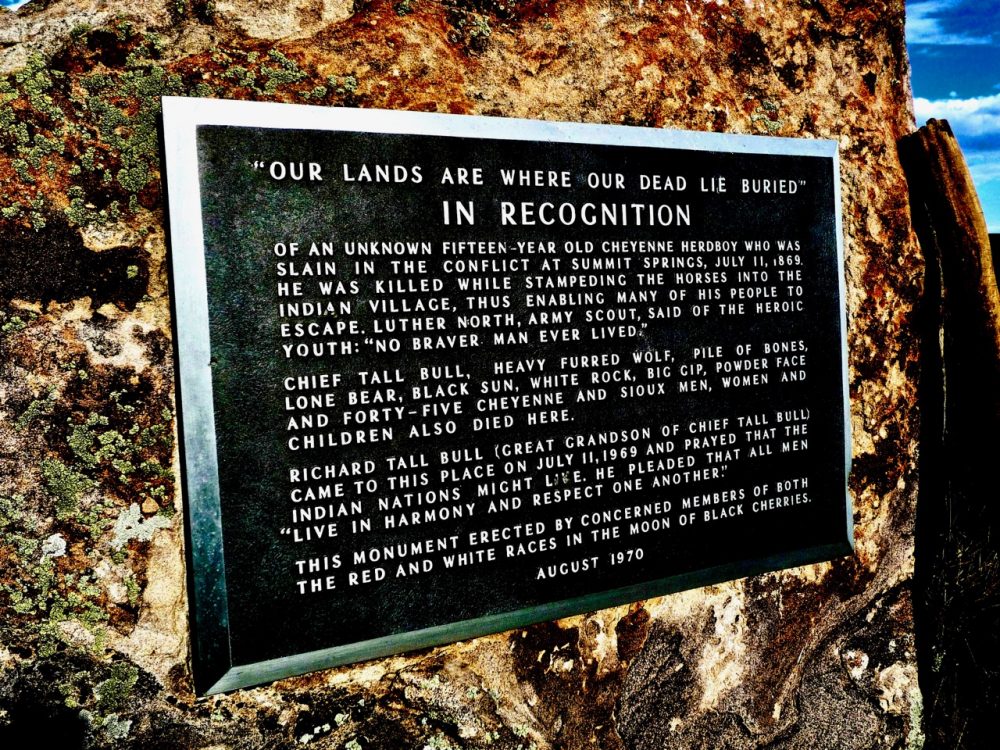

Cheyenne Bowstring Warrior Society War Chief: John said that in the early months of 1874 Medicine Water was chosen to become a war chief of the Cheyenne Bowstring Warrior Society. At that particular time the Bowstringer’s were the only Cheyenne warrior society who still had strength in numbers and were in a position to protect the woman, children and elders from attacks by the soldiers. The feared Dog Soldier Society was no longer able to protect the people after their devastating defeat at Summit Springs in 1869. John continued by saying that his great great grandfather Medicine Water then aged around forty years old was reluctant to take up this important position within the tribe as normally it would be a younger warrior in his mid to late twenties or early thirties who would occupy this position. After the chief naming ceremony and the smoking of the sacred pipe was completed Medicine Water vowed never to surrender to the white invaders and fight them till the death protecting his family and fellow Cheyenne. And his warrior wife Mo-chi (Buffalo Calf Woman) pledged to ride by her husbands side when fighting the Americans. Pictured below is one of two monuments located at the Summit Springs Battlefield in northeastern Colorado. I shot this image during my second visit to the site in 2010.

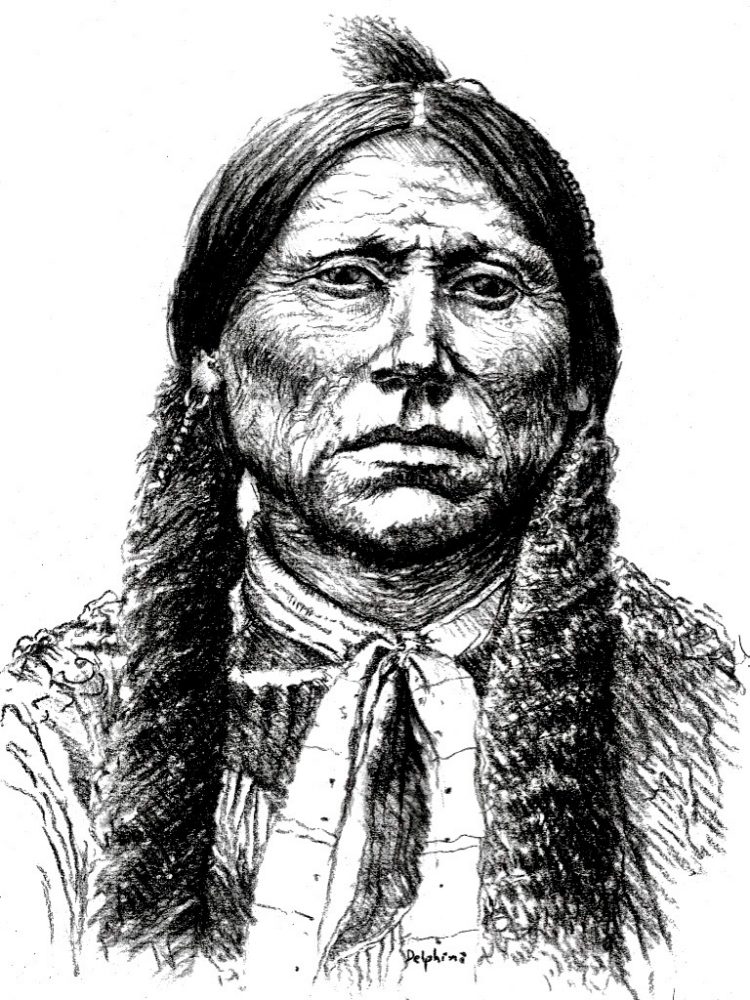

The Battle of Adobe Walls: The cups of tea and coffee were flowing fast and furious at the Sipes household that Sunday evening as John continued to tell his stories. John spoke about the attack by Medicine Water, Quanah Parker and their Cheyenne and Comanche warriors along with the Kiowa warriors against the buffalo hunters at Adobe Walls on the Texas Panhandle on the 27th of June, 1874 which was the initial engagement of the Red River War. The hunters were led by Billy Dixon and Bat Masterson and the firing from their .50-caliber Sharp rifles managed to stave off defeat against the attacking Indians. This incident opened the Red River War and for the next eight months there would be fierce fighting all across the Southern Great Plains between soldiers and Indians alike. After the Battle of Adobe Walls on the Texas Panhandle the warriors split up into their respective band groups and headed in different directions to continue their fight against the American invaders. Pictured below is a charcoal drawing of Quanah Parker by Paul Farley 1990.

German Killings & War On The Plains: John said that Medicine Water and his warriors include Mo-chi and his brothers Iron Shirt and Man On Cloud came across a emigrant family on the 11th of September, 1874 as they travelled along the Smokey Hill River in Kansas. John and Lydia German were heading west from their home in Georgia to Colorado Territory with their seven children. When the Cheyenne approached the German wagon one of the warriors shot John in the back and Mo-chi rode up and finished the job with a hatchet blow to the back of John German’s head. Lydia German was the next victim of the angry Cheyenne when a warrior struck her with a tomahawk. Three of the children were then quickly killed and the Cheyenne decided to take the four remaining German girls captive. The American Government used this deadly encounter as propaganda to justify their severe military tactics during the ensuing Red River War with over 5,000 soldiers sent into western Oklahoma. The American Government smear campaign focussed on how the murderous Medicine Water and his warrior wife Mo-chi had acted inhumanely with their deadly actions against the German family and their children. Pictured below is the Cheyenne Arapaho Colony Annual Powwow in western OKlahoma. I shot this image during my visit to the event in 1990.

Mackenzie & Palo Duro Canyon: I asked John what was the engagement between the Indians and the United States Army that was the tipping point during the eight month Red River War. John said that the war turned against the Cheyenne and their allies when on the 27th of September, 1974 at Palo Duro Canyon on the Texas Panhandle Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie with eight companies of the 4th Cavalry attacked a large village of Cheyenne, Comanche and Kiowa. The Indian casualties at Palo Duro Canyon were limited to only three dead that included Kiowa War Chief Red War Bonnet. What devastated the Indians was the capture of fourteen hundred of their horses. And rather than have the horses fall back into the hands of the Indians Colonel Mackenzie ordered them shot dead. And over the next six winter months the Indians from a lack of available food and shelter. The buffalo herds were almost gone and it seemed that surrendering at the Darlington Agency was the only option left to the chiefs Quanah Parker, Medicine Water and the other none reservation band leaders.

Sand Creek Painted Cheyenne Drum: On the Monday morning before Kim and I departed back to Los Angeles John and I spent a few hours after breakfast talking about the surrender of Medicine Water and Mo-chi at the conclusion of the Red River War. John said that before surrendering Medicine Water instructed eighteen Bowstring warriors to accompany Stone Forehead (Medicine Arrows) to head for the north country with the Cheyenne creation objects the four sacred arrows. It was agreed at a meeting of the tribal leaders that the arrows should not fall into the hands of the Americans after the surrender of all the bands who had decided not to head north to stay with their Northern Cheyenne cousins and relatives free in the Powder River country of southeastern Montana Territory. And on the 5th of March, 1875 Medicine Water, Mo-chi and the last Cheyenne warriors and their families surrendered at Darlington Agency near Fort Reno on the Canadian River in western Oklahoma. Pictured below is the painted drum that depicts how the Cheyenne people viewed the Sand Creek Massacre. It was a parting gift from John and Terry in 1996.

Fort Reno Indian Territory: The Cheyenne were escorted to their living quarters at Fort Reno but Medicine Water and Mo-chi were placed in leg irons for their active part in the German killings and led to the guardhouse. Young Sophia German one of the four surviving daughters said that Mo-chi was the one who had chopped the head of her mother Lydia with her tomahawk. And Catherine German told the story of how she was repeatedly raped and that Mo-chi seemed indifferent and sometimes delighted to see this happen to the young woman. John said there was no mention of what Mo-chi had witnessed to her own people and her family at both Sand Creek and the Washita River Massacres. And as far as John’s great great grandparents were concerned this was a war and their own actions were in retaliation for the brutal deaths of their people by the American soldiers. One of the four German sisters hand picked thirty-two Cheyenne, Comanche and Kiowa that included Medicine Water and Mo-chi as the main culprits in the killing of their family members and that the Indians would be transported to Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida to be detained as prisoners of war for an indefinite period of time. Pictured below is Fort Reno. I shot this image during my visit to the site in 2010.

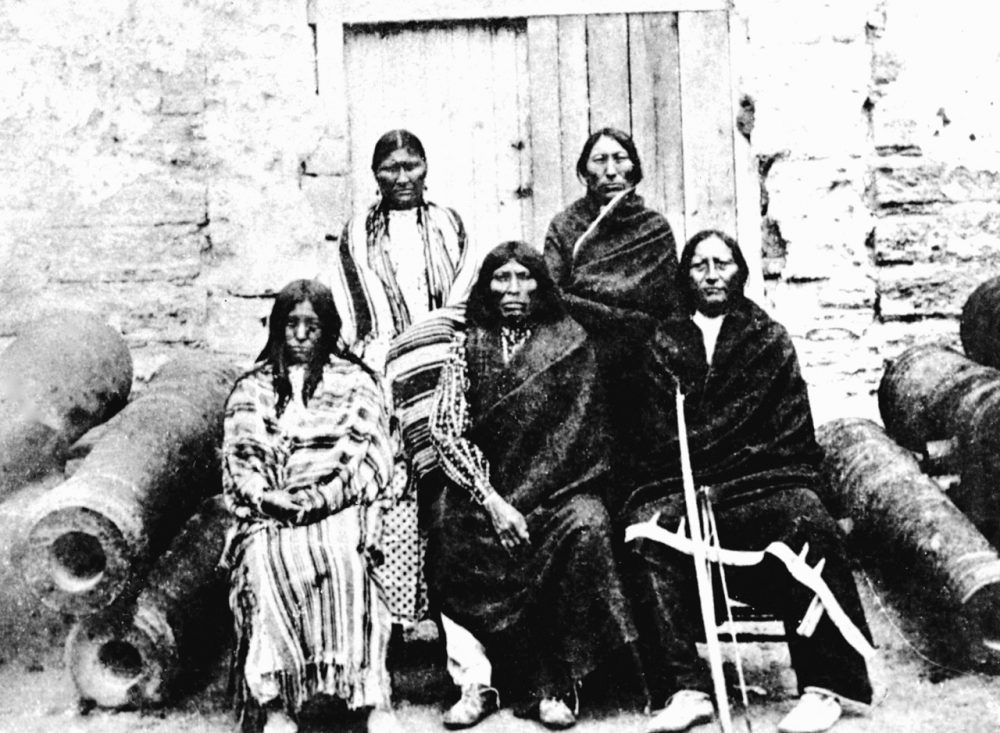

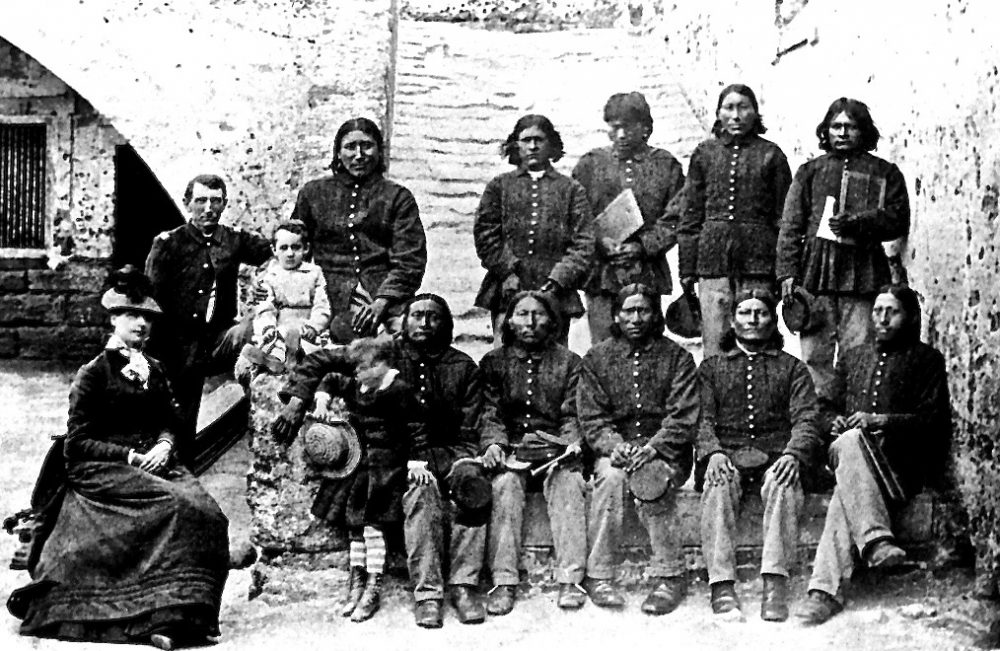

Fort Marion Imprisonment: The prisoners were then shackled in chains and transported for six weeks by train to Florida. Mo-chi was the only woman in the group of thirty-two prisoners. For the next three years Medicine Water, Mo-chi and the other prisoners remained captives behind the old Spanish walls of Fort Marion. And in 1878 they were finally released by the United States Government and returned back to Oklahoma. John said it was a huge adjustment for both Medicine Water and Mo-chi when they arrived back on the Cheyenne Reservation (Indian Territory) in Oklahoma. No longer were the people free to move around and the buffalo were all gone from the Southern Great Plains. Mo-chi had contacted tuberculosis while living in the damp and humid Fort Marion Prison. And three years after returning home Mo-chi died in 1981. She was aged forty-one years old at the time of her death. As for Medicine Water the old war chief lived a further forty-five years. He was employed to haul supplies between Caldwell, Kansas and the Darlington Agency. Medicine Water was also a member of the Native American Church that worked tirelessly to educate the younger generation of Cheyenne children. Pictured below is Mo-chi Buffalo Calf Woman top left and Medicine Water top right at Fort Marion 1875-1878.

Oklahoma Territory & Reservation Life: In 1891 Medicine Water received his allotment near Watonga in western Oklahoma Territory. And it was on this property that he lived into his old age. And in 1926 Medicine Water passed away and he was laid to rest with all the honours that befitted a Cheyenne War Chief of the Bowstring Warrior Society. As Kim and I were getting into our Chevy Lumina for the long drive he had one more story for Kim and I think think about as we drove west. Medicine Water in the last year of his life would saddle his horse and put on his old war shirt and ride the ranges in and around his property. If he came to a spot with a fence he would open the gate and ride through. And when riding at the side of the hard top roads he would force passing vehicles to slow down and stop and show their respects to a old Cheyenne War Chief. Pictured below are Mo-chi (Buffalo Calf Woman) top left and Medicine Water top right during their imprisonment at Fort Marion, St. Augustine, Florida from 1875-1878. Pictured below is Medicine Water’s Gravesite in Oklahoma. Image courtesy of the John L. Sipes Jr Family Collection.

Powwow: Native American Celebration: John and I kept in touch after Kim and I arrived back in Sydney, Australia in early September, 1996. His stories about his great great grandparents Medicine Water and Mo-chi (Buffalo Calf Woman) were indeed educational and inspiring to a fellow storyteller. And during a phone conversation in January, 1997 we agreed to write and develop a movie screenplay that included aspects of the Sappa Creek Massacre and the life of Medicine Water. And for the next five years when taking time out from our personal projects we enjoyed exchanging letters and speaking on the phone developing our storyline for the screenplay. When my Powwow: Native American Celebration photographic exhibition was selected for a three year national tour of the United States of America in 1998 it included one of the photographs of John in his regalia that I had shot during my weekend stay at his home in 1996. One of my projects in 2000-2001 was a collaboration with Chris Fisher a young nineteen year old musician from the Southern Highlands of New South Wales on a musical project. It was around this time that I had exhausted all avenues to interest directors and producers regarding the screenplay project. John and his wife Dee were also extremely busy working with the Fort Marion Prisoners families recording information for a future website. And they were also planning for a trip to St. Augustine in Florida with the prisoners families. Pictured below is the window display of the Powwow: Native American Celebration at Graphis Fine Art Gallery in the Sydney suburb of Woollarha in early April, 1997.

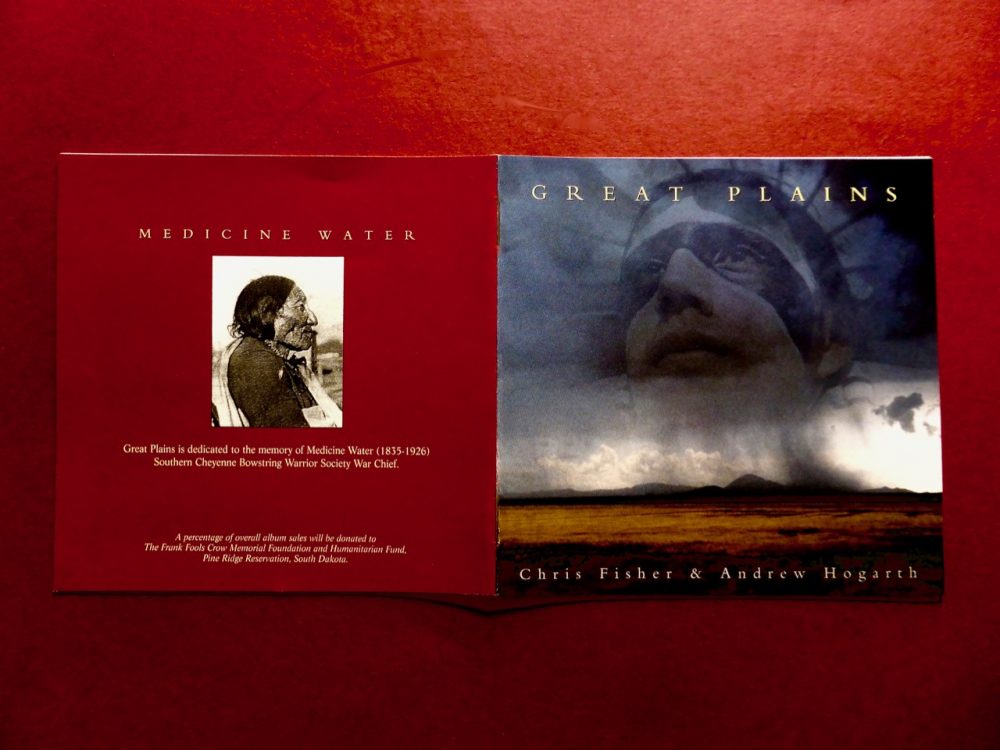

Great Plains Rock & Roll Album: When Chris and I had written and recorded nine songs for our “Great Plains” album that included stories about the Lakota-Sioux and Cheyenne. I decided that one last song was needed to complete the project and it would be a song to honour Medicine Water. I spoke with John on the phone in late June, 2001 and told him about what I was planning to do with a rock and roll song about the life and times of Medicine Water. At first he seemed surprised and I explained that I had hit brick walls with trying to interest people with our movie project. I said to John that a song seemed like a good avenue for our storytelling about Medicine Water and it would also find let us find a young audience if the melody and lyrical content struck a chord.

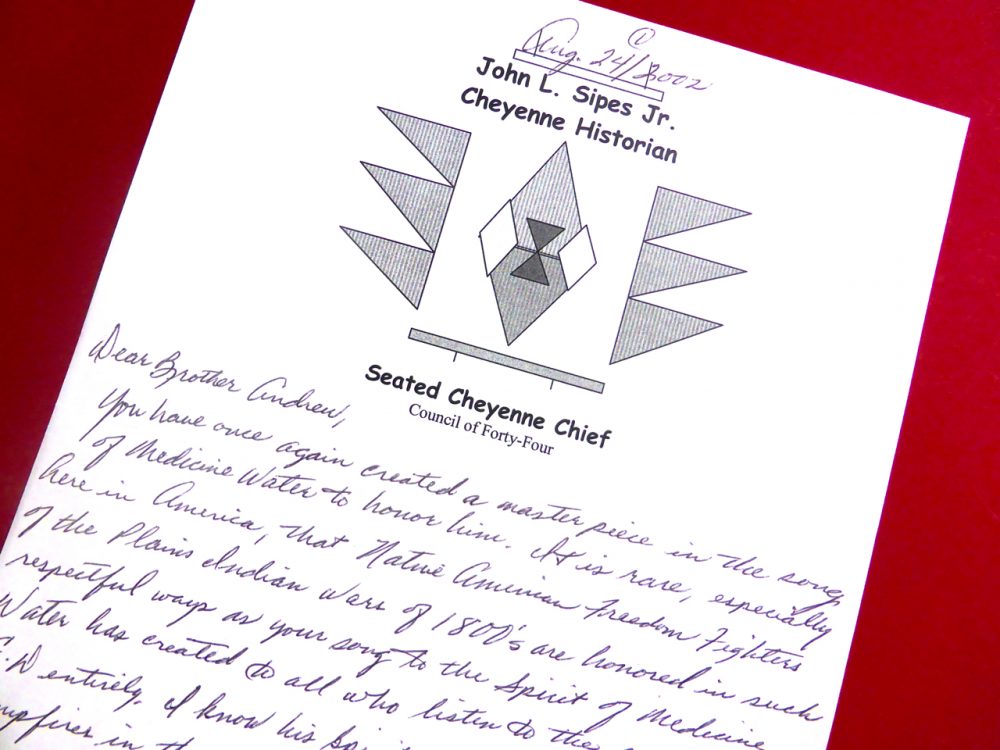

Medicine Water Dedication: When the “Great Plains” album was pressed for a second time John was kind enough to write up the liner notes for the Medicine Water song. Later I posted out copies of the album to his Norman home in Oklahoma and a few months later a letter arrived back in Sydney, Australia from John who was now a Peace Chief of the Cheyenne Nation. In the letter John thanked Chris and I for remembering his great great grandfather Medicine Water and recording a song about aspects of his life journey. This was indeed a nice way to finish an exiting music project that told stories of Lakota-Sioux and Cheyenne Freedom Fighters from the mid to late nineteenth century.

Visiting Castillo de San Marcos – Fort Marion: With the movie screenplay mothballed in 2003 I continued with my own personal projects while John did the same with his projects in Oklahoma. And although we kept in touch periodically over the next three years our day to day family commitments took centre stage and demanded more time. In early March, 2007 I received a e-mail from John’s wife Dee informing me that John had passed away after a short illness. This was indeed sad news to receive as our friendship had spanned over fifteen years and we always signed our letters with brother/friend. In early August, 2010 I travelled from Australia to St. Augustine in Florida to visit Castillo de San Marcos (Fort Marion). There I had arranged to meet with Amy Cassidy from the National Parks Service who operated the facility. Amy had meet John when he visited the site and together we looked through the photographic archives for images of Medicine Water and Mo-chi.

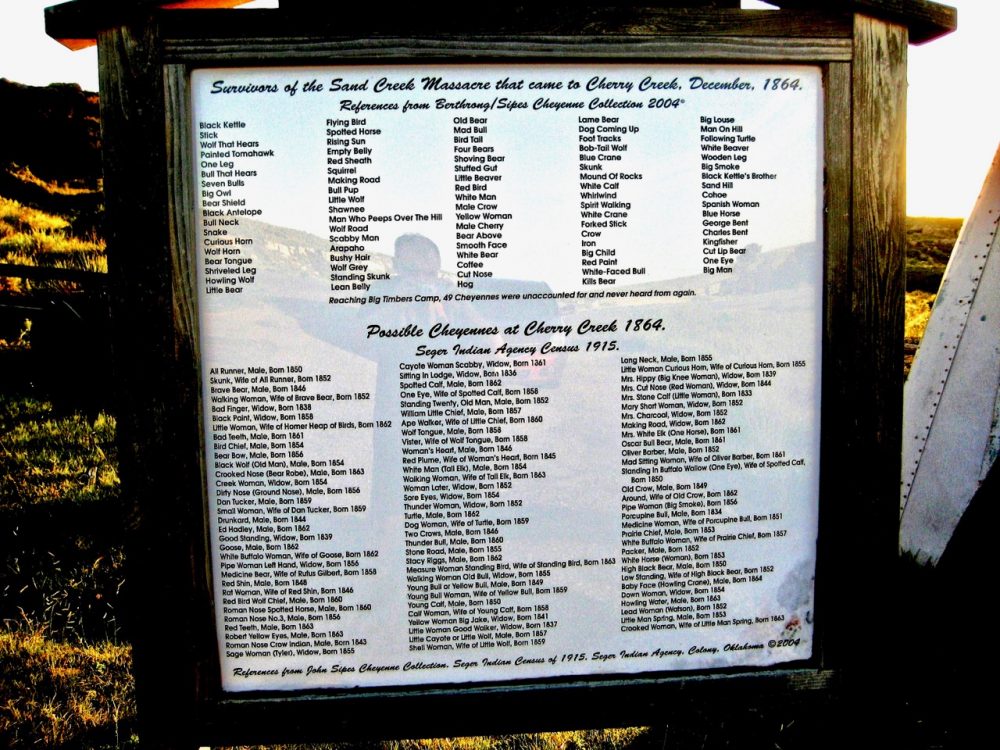

Following The Dog Soldier Trail: Together we discovered two images of Medicine Water and Amy informed me about what life was like for the prisoners during their three years of captivity at Fort Marion. Later I walked around the fort and knew that every second step was more than likely a step that Medicine Water and Mo-chi had taken. And with one of the historical images in my hand I was able to actually stand in the same spot where Medicine Water stood on the fort stairway. I thanked Amy for escorting me around the fort and the copies of the black and white photographs. Later I flew to back to Oklahoma City and I then followed the Cheyenne trail straight north to Montana. Along the way I stopped at Fort Reno, Darlington Agency, Washita River, Sappa Creek, Cherry Creek, Beechers Island and finally Summit Springs. This was Cheyenne lands where they camped and fought the Americans as they tried to save their culture and way of life in the recent past. And on a personal level this drive north was my way of paying tribute to a dear brother friend John L. Sipes Jr a Cheyenne Peace Chief and Tribal Historian who spent most of his adult life preserving the names of the ones who came before for future generation of all races. Pictured below is the sign with the names and dates of birth of Cheyenne who lived and camped around Cherry Creek and the surrounding area. The information was compiled by John.

Fort Marion Imprisonment: Pictured below is Castillo de San Marcos (Fort Marion) in St. Augustine, Florida. I shot this series of images while visiting the site in 2010. It was one of these rare places where I actually was able to walk in the footsteps of Medicine Water and Mo-chi (Buffalo calf Woman). It was great that Amy Cassidy from the National Park Service took me around the site and as I mentioned earlier in this post she had met John on one of his visits to the fort before his passing. We located one black and white image that actually showed Medicine Water standing on the fort stairs with a group of Cheyenne prisoners all dressed in their dark blue or black suits. Also interesting is the photograph of Medicine Water and Mo-chi seated looking at each other. One would have to wonder what their personal thoughts was at the very moment the photographer clicked the camera lens. It was documented that both were always watched by their Indian Mexican interpreter Romero as they made their way in and around Fort Marion. If the fort was a sad and somber place to visit then being imprisoned there for three long years would have seemed like an eternity for the free roaming plains Cheyenne, Comanche and Kiowa.

Pictured above is Medicine Water standing back row second from the right

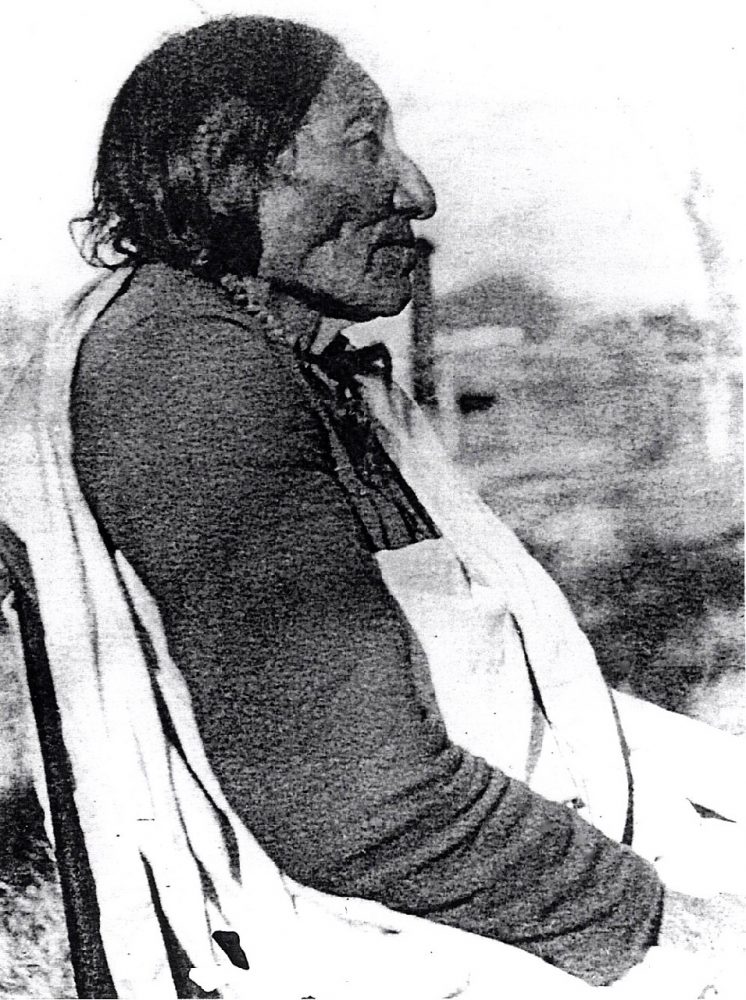

Pictured below is Medicine Water on his Watonga Allotment in 1925 shorty before his death the following year. Image courtesy of the John L. Sipes Family Collection.

Cheyenne & Arapaho Annual Powwow Program Colony Oklahoma 1992