Daily Telegraph

this is a short intro about the Daily Telegraph

click on the dates for the respective review

[tabs][tab title=”1984″]

The Sioux’s record set straight.

By Malcolm Andrews, The Daily Telegraph, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, Monday 11th March 1985.

There’s no denying that over the years Hollywood has given Indians a bad name. In the B-grade western movies we used to watch on Saturday arvos, the Indians were always the baddies.

As such, they used to get their just deserts, massacred by the good white Anglo-Saxon Protestants who pioneered the American west in wagon train after wagon train.

Naturally enough, when we played cowboys and Indians everyone wanted to be a cowboy. You only ended up as an Indian if you were the smallest and couldn’t stand up for yourself when the sides were chosen.

Even Andrew Hogarth understood that.

“Of course, when I was a kid I wanted to be a cowboy. It was always the Indians who got killed,” he said.

We say even when referring to Andrew because if there were cowboy and Indian games for adults, these days the 33-year-old Scot would undoubtedly want to be on the other side.

He is a self-taught expert on the Sioux Indians.

And he has just published (at a personal cost of about $20,000) a book in which he shoots down so many of the TV-inspired myths.

It sets the record straight about these proud people, who numbered among their ranks such names as the great chiefs Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse.

“I remember as a child, watching television shows like Bronco and Rawhide and even then I thought no one could be as bad as the way the Indians were portrayed,” Andrew said. “From that moment on I had a passionate interest in the Indian people.

“In 1981 I was one of the three million British people Maggie Thatcher put out of work so I decided to head off to Australia. I went via the United States of America to see first hand the places famous in Indian history – Crazy Horse Mountain, Little Bighorn, Wounded Knee and so on.”

It was to be the first of three visits to Indian country (a fourth is planned for two weeks time). On the last visit he met Jack Little, one of the last surviving full-blood Sioux

(it’s estimated that within 30 years there will be none left).

Jack, the curator at Crazy Horse Mountain in South Dakota, is regarded by many as one of the most radical of all the surviving Sioux.

Old Jack Little doesn’t have much time for white people but realised Andrew was different from your run-of-the-mill paleface.

“The white man will destroy life on this earth,” he told Andrew.

“He has been intent on doing this since he started up the hill of progress.

“The sad thing is he’s going to take all other people and forms of life with him.”

As well as chronicling the Sioux history, Andrew’s book, “Light at the End of the Tunnel,” tells Jack Little’s life story.

A photo of Jack hangs on the living room wall of Andrew’s Sydney flat, along with old Indian scenes and colourful artefacts.

There’s an authentic breastplate made from turkey bones and intestines and horses hair and, of course a “peace pipe.”

“Here’s another Hollywood myth.” Says Andrew.

“Television and movies would have you believe the Indians sat around having a puff every evening.”

“But it was really a spiritual thing, used only in special ceremonies.”

Less than spiritual are the video tapes sitting next to Andrew’s television set- the movies “A Man Called Horse” and “Soldier Blue.”

The fact that Andrew holds the Indian culture in high esteem, if not awe, is obvious.

Just as obvious is his contempt for that famous old cavalry officer General Custer.

“Custer saw the destruction of the Sioux and Cheyenne village in the Little Bighorn as a way of enhancing his prospects of becoming the President of the United States,” Andrew says.

“He was oblivious to the danger to his men and attacked despite warnings by his Indian scouts.”

It’s history now that not only did Custer not make it to Washington, he didn’t even make it past Little Bighorn.

[/tab]

[tab title=”1988″]

A Sydney paleface tells of life among tribal Indians.

By Marianne Bilkey, Thursday, The Daily Telegraph, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, 10th March 1988.

Andrew Hogarth has had a fascination with American Indians since childhood.

As a boy in Scotland he refused to watch movies with his mother unless they were about Indians instead of cowboys.

Now, after three working trips to America, the Sydneysider has captured his lifelong interest in print with the release of a book about the Plains Indian.

Andrew, a camera operator for The Daily Telegraph, wants people to understand the anguish the Indians experienced during the early years of their battle for freedom and acceptance.

“I suppose I became interested in the Indians because like them, I’m a bit of a radical,” he said.

Andrew’s interest has taken him across 96,000 kilometres of America in search of information.

“They were subdued in America from 1854 to 1890 and even after that they had to fight for acceptance.”

“This book concerns itself with those years, with modern photographs, historical photographs, a brief history of the actions, and a guide on how to find these places.”

In the book “Battlefields, Monuments and Markers,” Andrew writes: “Unlike my birthplace, Edinburgh, with its castle, palace and wealth of old buildings, sites concerned in this publication do not offer the visitor such monuments to one culture’s dominance.”

“The great western plains of the United States do not share the claustrophobia and crowds of Europe, but offer the visitor a rawness and a chance to experience the often unsurpassed beauty of the plains.”

The book is the second Andrew has written about Indians.

[/tab]

[tab title=”1990″]

Brave Crusader.

Much has been written about South Africa’s blacks, but Native Americans are battling for space on the world stage. Scottish-born Australian Andrew Hogarth has dedicated a part of his life to their plight and told Adam Walters of his battle.

The Daily Telegraph, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, Saturday 10th March 1990.

Andrew Hogarth maintains that tales of how the west was won should trigger memories of triggers, and how the Native Americans didn’t have many to pull. Instead, he says Hollywood has adulterated a graphic history of mass slaughter to portray the illusion of a fair battle between the “goodies and the baddies.”

Many a film studio has romanticised the heroes of America’s early pioneers, but Hogarth will argue until he is red in the face, that the settlers were the villains and the Native Americans the victims.

Born in Edinburgh, Hogarth has an unlikely background for a human rights activists, and he is the first to admit his research of Indians began as a hobby. A former journalist with a soccer magazine, his involvement would grow from part-time interest to total fascination, as his three books and many articles on the subject testify.

In his latest text, “The Great Plains Revisited,” Hogarth employs the talents of artist Paul Farley to capture the wisdom of the last great Lakota-Sioux Ceremonial Chief Frank Fools Crow. Farley’s sketches are dominated by portraits of Hogarth’s heroes. In fact the book was dedicated to the memory of Jack Little, Bill Tallbull and Frank Fools Crow. All three men are direct descendants of the Lakota-Sioux and Cheyenne chiefs who fought to repel the genocide of their proud tribes during the Plains Indian Wars of the 1870”s.

For Hogarth they have almost become mentors, but it would be wrong to mistake his respect for the great men as an emotional preoccupation. He talks with authority and objectivity about how “imaginative” script writers fictionalised the pioneering days to the point of creating popular perceptions. “ I’ve set out to try and destroy the misinterpretations given to people by the American movie industry,” he said.

“A close study of the history books will reveal the exact opposite of what we see in the Saturday afternoon westerns.” He points out that the Native Americans of the Great Plains had not seen guns before the bloodthirsty arrival of white men from the east coast. Thankfully the bow and arrow are synonymous with Indians because that’s all they had. That humble weapon is about the only thing Hollywood has done to give an accurate impression of the hopelessness faced by Indian tribes when their land was being stolen.”

His book contains a detailed map of the locations and dates of battles, including the day Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer and 265 men of the Seventh Cavalry fell at the Little Bighorn valley in south-eastern Montana.

With the Lakota-Sioux and Cheyenne Native Americans combining forces to protect their families and land, Custer’s entire command was wiped out within two hours of charging the village. According to American folklore Custer died a hero, but he was in fact the victim of his own bad timing. Custer’s Last Stand has become a legendary chapter in the United States history books, but as Hogarth points out, the deaths of his Lakota-Sioux and Cheyenne counterparts hardly rates a mention at the battlefield today. “The Lakota-Sioux and Cheyenne chiefs were the political and spiritual leaders of their time, and they defended their land instinctively – they were not the aggressors.”

The damage caused by the unforgiven unrelenting march of so-called Manifest Destiny in the United States of America during the nineteenth century, was not restricted to heavy Native American losses. White man’s invasion has left a legacy of humanitarian, social and environmental issues as disturbing as the problems faced by Australia’s Aborigines.

The poverty on some reservations provides a sickening third world contrast to the more familiar bright lights of modern America. Hogarth said, “The parallels between Native Americans and Aborigines are as finite as the injustices inflicted upon them by the English speaking world. Just as Aborigines are fighting to keep their land, the Native Americans are constantly attempting to fend off governments and multi-national companies.”

Hogarth said, “The never ending battle for the Native American people to protect their reservations and sacred sites from mining and other damaging ventures can be likened by the fight to save Australia’s Kakadu National Park. The rifles and pistols of the wild west might have gone, but the white man’s gun is always smoking in Washington. There have been countless delegations of Indian chiefs and elders who have spoken to politicians, but nobody wants to know about them.”

It is that frustrating pursuit of fairness, which continues to inspire Hogarth in his personal attempts to help his Native American friends tell their side of the story. “I have paid for the production of my books from start to finish. By publishing independently I can control what is let out into the public domain. The oral history passed down through the generations is written down once, and not tampered with by the large publishing houses and their editors, satisfying their own personal agenda.”

“The trips to the Great Plains region of the United States of America over the last decade, the research, travel costs, photography, text layout and printing have all been financed by my own pocket through working jobs, and selling my books to independent bookshops, and interested individuals along the way.”

Hogarth has certainly came a long way from the young teenager in Edinburgh, Scotland, who was told at the tender age of fifteen by the school headmaster that he could not continue with further education. Luckily his skills developed in the field of graphic reproduction and printing, have allowed him to express his passion for the Native American culture through the printed page and photography.

[/tab]

[tab title=”1994″]

Images of the Red Man’s life: ‘I wondered where the Indians went after the attacks.’

By Stewart Hawkins, The Daily Telegraph, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, Saturday 8th October 1994.

A childhood fascination with westerns led photographer Andrew Hogarth on a pilgrimage to the American West that was to take him ten years and across 148,000 kilometres. The photographs he took have been assembled into an exhibition entitled Native Lands: The West of the American Indian.

Hogarth said: “It was the Saturday afternoon serial stuff I grew up with, shows like Bronco and Rawhide where the Indians were mostly portrayed as the bad guys that made me want to find out what it was really like. I also remember as a kid I read this small novel about a white man who went to a little hut in the middle of nowhere and there was an Indian living there, who told his story about his people.”

“I wondered where that hut was and I wondered where the people are now. And in the movies, I always used to wonder where the Indians went after they’d finished attacking the wagon trains.”

“I from the western indoctrination period of entertainment, but there was always that little book about that person, being interviewed by the white man.”

His quest to photograph the largely undocumented modern lives of the native people of America resulted in 700 images which he has culled to forty-three for the exhibition. Hogarth travelled seven times through the traditional lands of the Apache, Navajo, Cheyenne, Sioux and Arapaho among others. He said the mages he collected showed the dignity and pride that native Americans have rediscovered in their culture and history.

He first visited America in 1981 after reading Dee Brown’s novel “Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee” about the last campaign of the Indian Wars in 1890, when 298 Lakota-Sioux Indians were massacred. He wanted to visit the battle sites but ended up meeting a number of native Americans and decided to begin photographing them.

“I started to read about these names, Crazy Horse, Little Wolf and Geronimo, and Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee was just one sad story after another,” he said.

“I wanted to visit the places where these incidents had happened. That project led me into contact with native Americans and when the opportunity arose and friendships developed, and only then, would I photograph.

“In the 1880’s there was quite a bit of photography done, Wounded Knee was photographed extensively. There’s hundreds of pictures of bodies lying everywhere.”

“But during the next seventy years there was not a lot of documentation and the Indians were just forgotten. Our culture has a photographic record of every day of life, but the native Americans have not.”

After the massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890, a Lakota-Sioux medicine man called Black Elk said: “The sacred hoop was broken, and the people are no longer together.”

He was almost right. The native American population was estimated at six million in 1492, when white men first discovered America. By 1890 their numbers were around 250,000. Today the population is increasing, native Americans now number one and a half million people in 1994.

[/tab]

[tab title=”1997″]

Tribal tributes

By Caroline Chisholm, The Daily Telegraph, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, Friday, April 11, 1997.

“Two years ago, Scottish-born Andrew Hogarth quit his steady job in Australia and set off to travel around America to sell his books. Now, with thousands of kilometers under his belt, not to mention book sales, Hogarth is bringing the subject matter of his efforts – photography of Native American Indians – back to Sydney. Hogarth has photographed American Indian culture over sixteen years and has produced four books, Lakota Spirit, Battlefields Monuments and Markers (about the American Indians’ battles with the United States government), Cheyenne Hole and Native Lands.

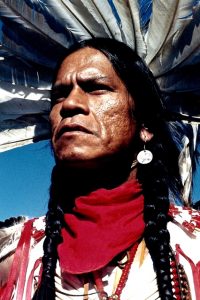

The photographs also have appeared in numerous exhibitions, and while Hogarth was selling his work in the United States, he took enough shots for another exhibition. This exhibition, called Powwow: Native American Celebration, is making its debut in Sydney.

“It’s the American Indian people coming together in their culture for a celebration,” Hogarth said. Every member of the tribe gets involved in making regalia from traditional hides and beadwork, and Hogarth remembers being at a powwow last year with about 10,000 present. “The atmosphere is just tremendous and they’re in the middle of nowhere.”

He always intended to record images of native Americans to bring understanding of the Indians into a modern context, because few images have been collected since the early sepia days of photography. ‘The three exhibitions have introduced people to Indians who are living today, and following their culture today, and that’s important because it takes the American Indian out of that time warp.”

But why would a self-taught Scotsman travel across the United states of America to record another people ? ‘I grew up on a ‘reservation’ – a housing estate with 3,000 families, no amenities, a church with a minister who used to put the fear of God into us, a chip shop.

“If the minister didn’t get you, you’d probably end up with bowel cancer from eating all the pies and greasy fish. I would go into the reservations with this Scottish upbringing. I don’t go into the reservations and knock on doors, because if someone had done it to me in Scotland all those years ago, I know what I would have done to them!

“Being a Scotsman, I basically got in amongst it and saw where the bullets flew, and then I tried to create an image for posterity. Nobody else was doing it.” Hogarth said his hobby was never intended to become a livelihood, but admits the prospect of national exhibitions in America is exciting.

His three exhibitions will soon be available to Exhibits USA, a company with access to 7000 museums and art centres in America. Exhibits USA frame, mount and package exhibitions and also have access to colour publishers and CD-ROM producers, so Hogarth is hoping the possibilities for use of his work are endless.

“I never thought it was going to be like this, “Hogarth said. “I thought it would be nice if people went in the stores and purchased the books – but then the Battlefields book sold out. I had 3500 copies. He still uses the camera he has had for sixteen years, an Olympus OM 20, with one 35mm to 75mm zoom lens.

His approach to his United States travels is equally pragmatic: “I’m just pleased to have survived it. I’m not a roadside casualty. I haven’t been dumped behind one of the bars as I was having a few beers and trying to hang out. One of the hardest things you can do in your life is come between two cultures which don’t have a lot of respect for each other.”

Powwow: Native American Celebration, Graphis Fine Art Gallery, 150 Edgecliff Road, Woollarha, until April 30.

. [/tab][/tabs]

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.