Indian Nation “Powwow”exhibit focuses on tribes traditions

by Kimberley McGee

The Las Vegas Sun, Nevada, United States of America, 26th February, 2002.

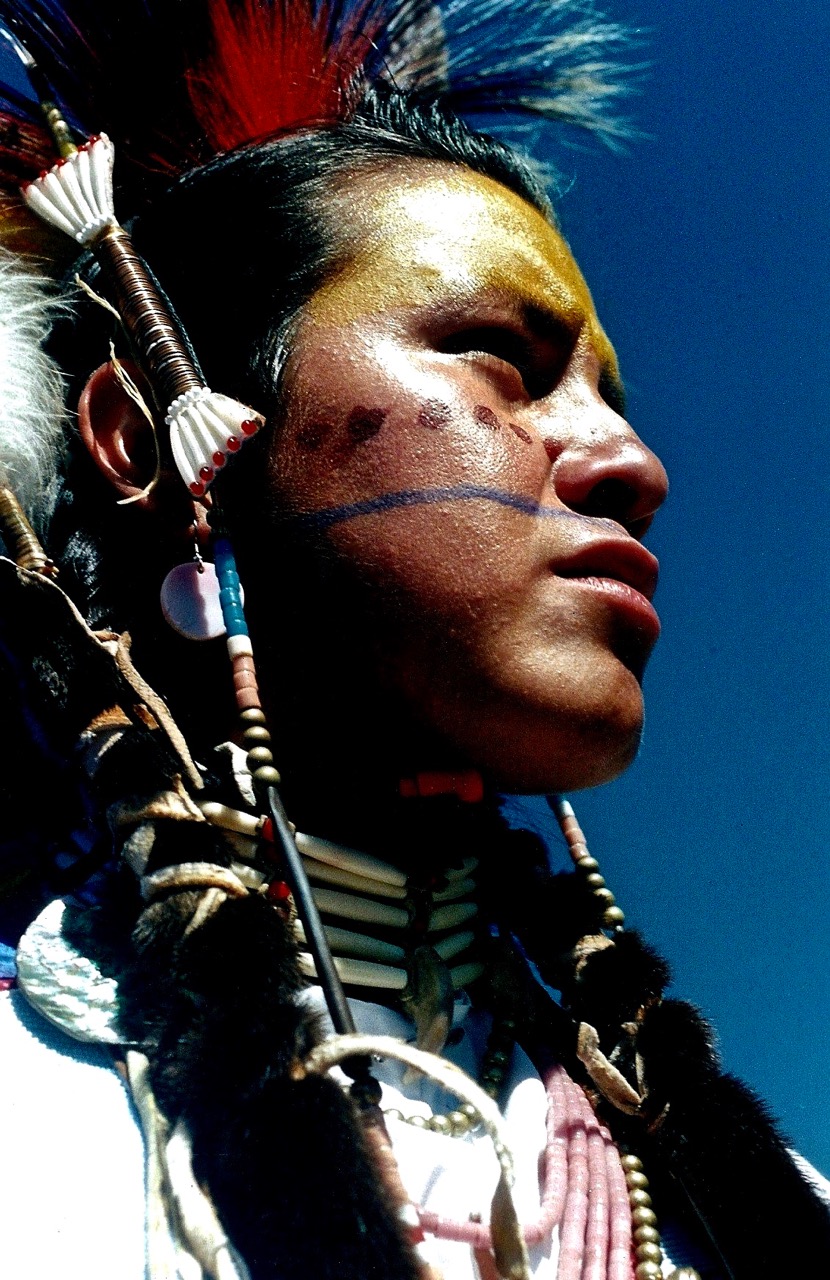

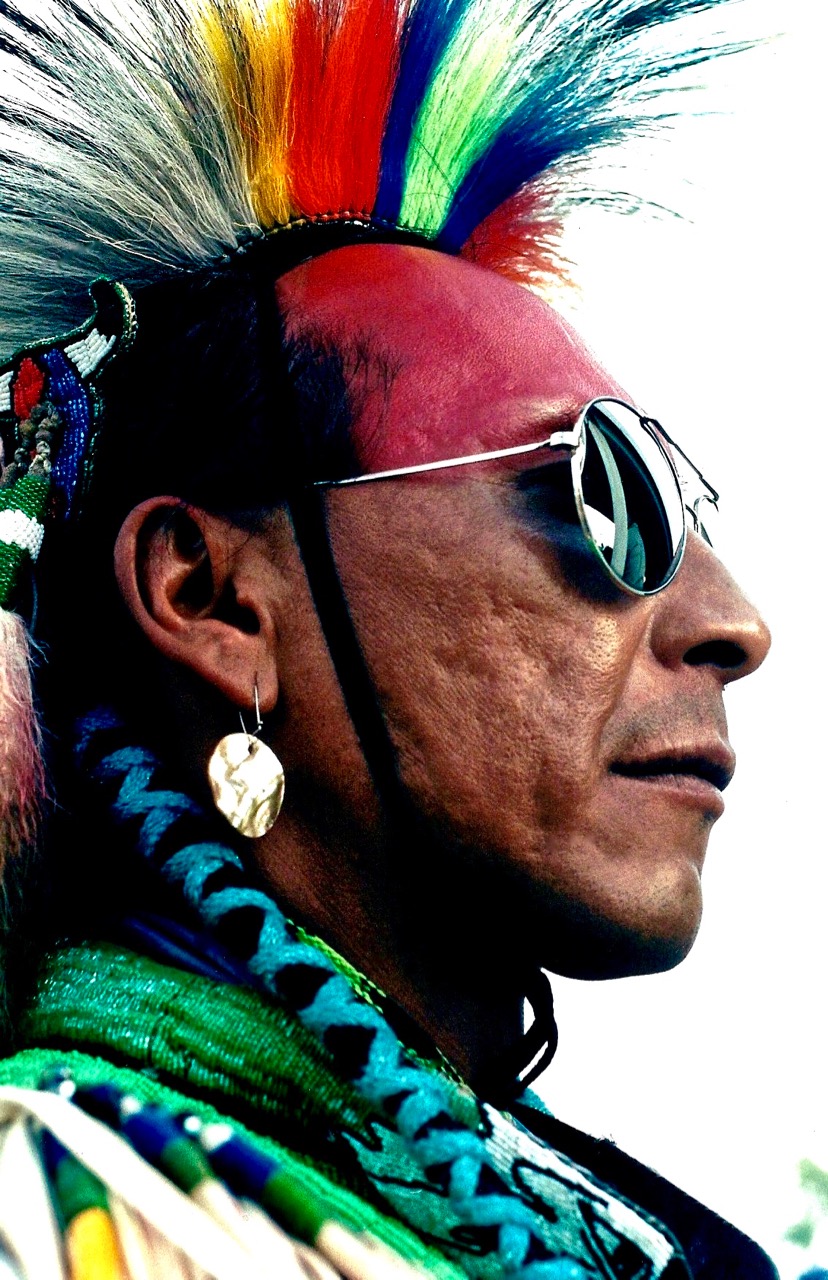

The painted faces of American Indians in Scottish photographer Andrew Hogarth’s photos shine with fierce pride. The faces are a reminder of the past and present. Their ceremonial headdresses, breastplates and footwear for annual powwows have been carefully documented by Hogarth in the “Powwow: Native American Celebration” exhibit, on display through April 28 at the Clark County Heritage Museum.By Kimberley McGee. The Las Vegas Sun, Nevada, United States of America, 26th February 2002.

“We thought this really showed American Indians in a way that we hadn’t seen before,” Chris Leavitt, Curator of Education for the museum, said. “This is an exhibit to teach about our local Indian culture as well as the national culture.” Powwows are competitive events where dress and dance styles are judged. They include many tribes and present an opportunity to compare dance techniques, dress and a chance to take pride in Indian culture. “They are a large part of American Indian culture that isn’t always seen by the public,” Leavitt said. “For some, this is the first time they have ever seen an Indian dressed up in fancy dress for a powwow. Hogarth really captures contemporary Indians.”

“We wanted something that would show another side of Indians that people don’t see locally,” Leavitt said. “This is something people don’t see here (in Las Vegas).” The 54 photos by Hogarth depict Indians in festive powwow regalia. Included in the exhibit are traditional Indian dress artefacts from around the country, such as robes and headgear, as well as a large powwow drum, pipes, feathers and beaded shawls.

The large photos are a procession of colour. The powwow dancers don eagle feathers, buckskin, fringe, jingles, beadwork, ribbon work, blankets, turquoise, shells, bells and quills. The costumes are worn with respect to the birds, animals, fish, Earth, water and sky that are a large part of American Indian culture.

“This is one of our most popular exhibits,” said Lisa Cordes, development coordinator for Exhibits USA, which finances the travelling show. “It’s been all over the southwest and it has drawn a lot of people.” The exhibit takes an educational approach with interactive objects. Children can try on anklets and jingle cones, which are used in traditional powwow dances. Guests can also witness beadwork in the making and learn how the intricate breastplates and headgear is traditionally made. Visitors learn there are 557 federally recognised nations, or tribes, in the United States. Through the powwow, American Indians honour the traditions of their ancestors and pay tribute to the people of tribes today.

Hogarth’s interests in American Indians was sparked by Saturday matinees at movie theatres in Edinburgh, Scotland, in the late ’50s and early ’60s. The images of Indians on horseback stuck with Hogarth, who made a pilgrimage to the United States in the ’80s to record the American Indian culture with his camera. Hogarth travelled more than 150,000 miles in 17 years to capture the traditional and contemporary moments of Indian gatherings. Hogarth, who now lives in Australia, has said that his fascination is with the living people of an ancient tribe.

“We wanted to bring a flavour of American Indians that was different and presented education opportunities,” Leavitt said. “These are pictures of plains Indians, which a lot of people in Nevada don’t get a chance to see.” The Southern Nevada Indians are much different than those depicted in the Midwest, said Norma Naranjo, a clerk in the Indian education department for the Clark County School District.

But the fact that the culture is held in Hogarth’s high regard for the world to peek into a powwow is significant, Naranjo said. “It’s important for everyone to understand who they are and the powwows give Indians a chance to see their history and their contributions to society,” Naranjo said. “We are very diverse. People don’t understand that.” Through exhibits such as Hogarth’s there is a chance that people might understand the many different faces of American Indians, Naranjo said. Naranjo is a Hopi Indian, which she said differs physically and culturally from the other Indian tribes in Nevada.

“We are not anything like our neighbours, but people group us all together,” Naranjo said. “Just because we live in the same state doesn’t make us the same. We are as diverse as African-Americans or any other people. We don’t like to be stereotyped.” Naranjo attends annual powwows to catch up with neighbours and to celebrate the culture. She admires the beadwork by the youth and shares in the stories of the elderly tribe members.

The powwows offer Naranjo and others an opportunity to revel in the culture. “It’s important for people to recognise we are not dead,” she said. “We are a living culture.” Naranjo attends powwows in the spring and summer. They offer a chance to recognise each tribe, its contributions to society and the American Indian culture and visit with friends of all cultures.

“The powwow circuit gives us all a chance to come together and learn from each other,” Naranjo said. “That’s why we keep it alive today. It’s a chance to visit and enjoy and celebrate with everyone.” As a teacher of Indian culture, Naranjo has shared the recipes and traditions of her culture with elementary school students throughout the valley. It was in the schools that Naranjo learned how easily the Indian culture can be forgotten or misunderstood.

Twelve years ago a young student asked her a question that shocked her, and shored her resolve to share her culture with the world. The boy peppered Naranjo with questions about American Indians, and asked if she was a true Indian. When she affirmed her ancestry, he shyly asked if Naranjo was a ghost. The child thought American Indians were a people of the past, not the present. “He brought to me the need for us to get out there and let people know we are here and contributing to society,” Naranjo said. “That’s what you learn at a powwow, how we contribute and the pride we have as a culture.”

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.