Native Heart: Photographer Andrew Hogarth idolised movie cowboys

until he discovered the story’s other side

by Rosemarie Milson

Sunday Life Magazine, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, 13th April, 2003.

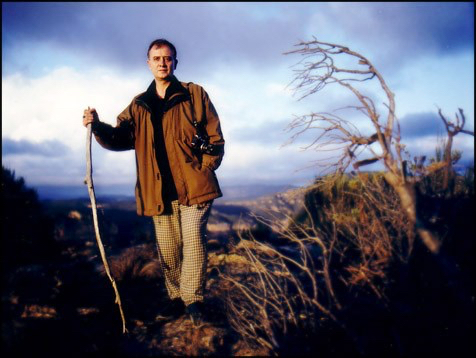

Self taught photographer Andrew Hogarth is sitting in his second-floor apartment in Sydney’s east, talking in a soft Scottish brogue about his tumultuous upbringing in a housing estate on the outskirts of Edinburgh. It was a tough existence; money was tight, alcoholism permeated family life and neighbourhood gangs and petty thieves flourished. He and his younger brother and sister would sometimes go hungry when their electrician father drank his earnings. As the 52-year-old describes how he would lie in bed as a child, rigid with fear while his father bashed his mother and spat abuse, larger-than-life framed portraits of native Americans form a striking, seemingly incongruous backdrop.By Rosemarie Milsom, Sun Herald, Sunday Life Magazine, New South Wales & Victoria, Australia, 13th April 2003.

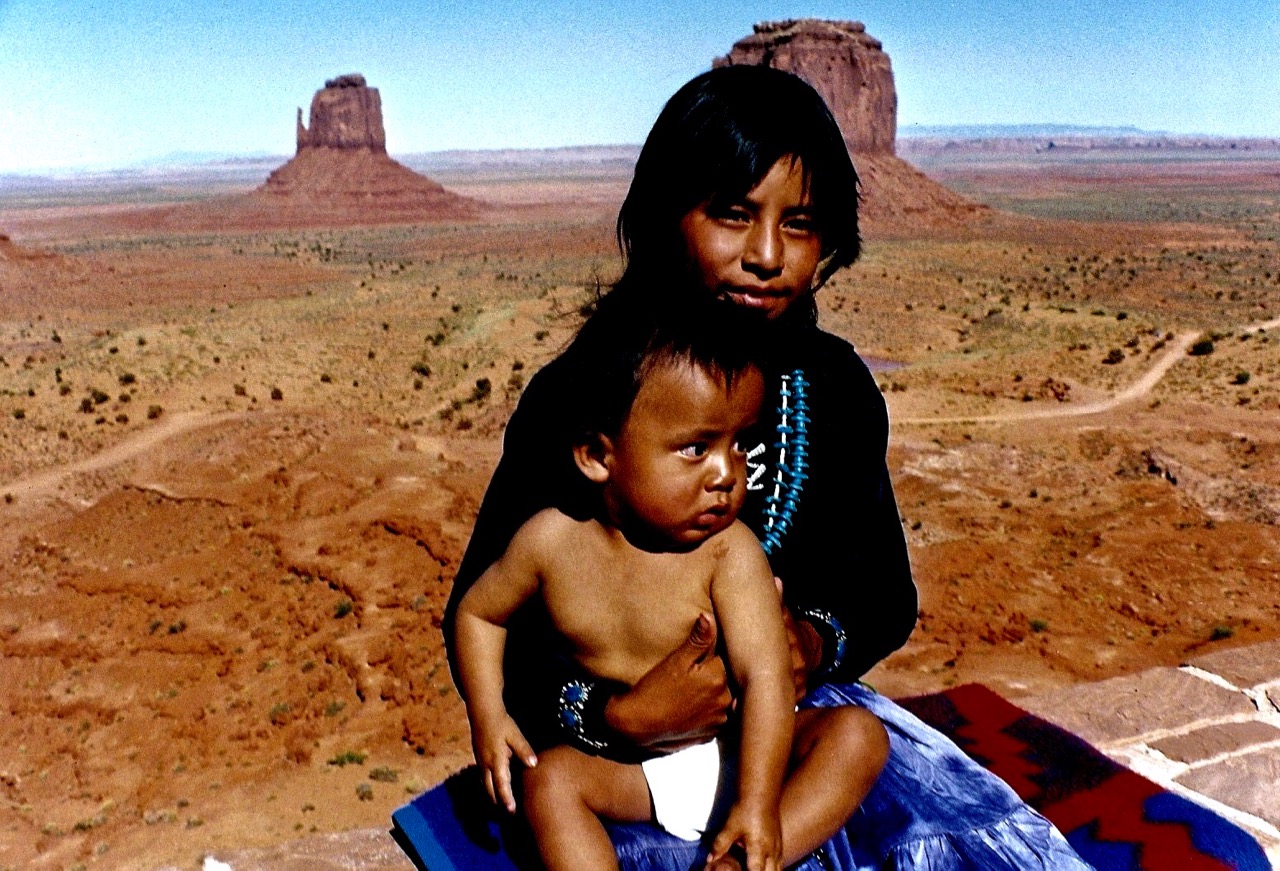

There’s a photograph of 21-year-old Jay Eagle, a traditional Lakota dancer with long, raven pigtails wrapped in white ribbon, his feathered headdress forming a dramatic ceremonial halo. Lining the hallway are more images: Roy Pete, a burly Navajo dancer with a red, black and white mohawk, and nearby a majestic Khena Bullshields with her distinctive cheekbones, full lips and leather and bone breastplate – looks to the distance.

These are all Hogarth’s images and they form part of his travelling exhibition Powwow: Native American Celebration, which is nearing the end of a three-year tour of United States museums, cultural centres and art galleries. He has also written and self-published five books of native American history as well as initiating and publishing a sixth book, Lakota Spirit, an autobiography by respected Lakota leader Jack Little, written before his death in 1985 with the help of his wife, Shirley. Hogarth’s internationally renowned body of work has come at great personal expense and he now works as a porter at an aged-care hospital to subsidise his passion.

The story of how a sensitive Scottish lad who rarely spoke until he was 12 (“People thought I was a bit simple”) and ended up spending 20 years documenting and photographing the history and ceremony of native American life is full of dramatic twists and turns. Interestingly, it was TV and film that triggered Hogarth’s fascination with native ‘American culture. “My home life was a mess until I was 15 and started working [as an apprentice graphic reproduction camera operator],” says Hogarth. “Sometimes my father would turn out the power after beating my, mother badly. He never touched us kids, although he nearly killed me one time by throwing a can of beans at me. I turned my head and the can crashed into the side of my skull, fracturing it. Through all of this, I had my western serials, which started in the evening around 6.30, and I’d go to the cinema.”

Hogarth idolised the cowboy stars of Bronco, Rawhide and Maverick. To a boy desperately seeking a role model, James Garner and Clint Eastwood offered it all. The local cinema ran two westerns every Saturday, with Bugs Bunny cartoons in between.

“It was all Apaches, wagons, cowboys and guns,” says Hogarth. But it wasn’t until he stumbled upon the gory final scene of Soldier Blue that he was confronted with the ugly side of America’s past. Starring Candice Bergen and Donald Pleasance and based on the 1864 massacre of more than 500 members of a Cheyenne tribe at Sand Creek, Colorado, by the US cavalry, the film features horrific violence (and is not to be confused with the censored version seen on TV).

“I saw these cavalry men burning tepees and a Cheyenne woman ran towards us on the screen and a man on a horse came up behind her with a sabre and whack, her head just flew through the air and then her breasts were cut off. Other women were raped and children were murdered. It had such an impact. Here I was at 22, and up till then nothing I’d seen on TV or at the cinema portrayed native Americans as human. There were bits and pieces patronising them and they were usually portrayed as people who deserved to be subjugated and exterminated at all costs.”

Fuelled by the injustice of the massacre, Hogarth immersed himself in the bloody history of the native Americans. He could see parallels in the treatment of the Scots at the hands of the English and, of course, there was his own stormy upbringing. In 1981, he finally seized the opportunity to visit America’s Great Plains.

“I was 30,” says Hogarth, “and I was married and owned a house. I was being told that this stuff was important in the scheme of life. But I started to feel like there was something more out there.”

Not long after, Hogarth was retrenched, his marriage crumbled and he sold his house. “I became one of many Thatcher casualties, and, no, it’s not like being injured or killed but it’s still traumatic. I remember consciously deciding to find my passion. I ended up booking a trip to America and I bought a camera. I got on a Greyhound bus in Los Angeles and headed to South Dakota and the Black Hills, the sacred heart of the Sioux nation.”

Hogarth visited Crazy Horse Memorial, an ambitious project that began in 1939 “When Sioux chief Standing Bear invited sculptor: Korczak Ziolkowski to carve a monument to the great Sioux warrior Chief Crazy Horse, the mastermind behind the defeat of General Custer in 1876. Crazy Horse never allowed himself to be photographed, so his huge image, which is still being carved in a mountain in South Dakota by Ziolkowski’s successors, is symbolic of all native Americans.

It was there that Hogarth met Jack Little, a respected native American guide who would later take Hogarth up on the offer of publishing his autobiography. It was the first of many friendships formed during Hogarth’s 10 trips to the US (Hogarth settled in Australia in the mid-70s). In the beginning, he rarely photographed people, preferring to focus his rudimentary skills on recording 80-historical battle sites scattered across the Great Plains region.

“I would never enter the reservations,” says Hogarth. “I wasn’t there to march in and make people feel uncomfortable. To get respect in that part of the land is very hard. I ended up buying an Olympus [camera] and gradually I started photographing people always in natural light and only with their permission.

“Of course I’d get asked if I was going to use the image to make postcards. The idea of a ‘white man’s camera’ does not sit easily with most [Great] Plains tribes.” But how did an Australian resident, with a Scottish accent gain the trust of his subjects? “It helped that Mel Gibson’s movie “Braveheart” was screening around the time of my Powwow idea,” Hogarth grins. “I’d say did you see my movie, and people were more open with me. I also think my upbringing gave me the skills to relate to them. With some of the smaller powwows, if you didn’t have a personal invitation, nobody would speak to you.”

Hogarth pursued his passion in between working in the graphic design printing industry in Sydney. He poured his money back into his publishing and photography projects, often selling the books from the back of his hire car during his travels. He has participated in 26 exhibitions since 1994, both here and in the US. His main aim has been to educate and inform, a role he hopes to continue by visiting high school history students and talking about his experiences.

After 20 years of travelling, Hogarth is pausing. The camera is packed away and he is working on his autobiography while earning a modest income as a porter. On a coffee table in his lounge room are three wooden boxes with brass clasps. Inside are 700 negatives – culled from thousands – and the key to Hogarth’s sense of self.

“It was important to me … to find something to do that had more soul. After losing my job, what was I going to do? Buy another house, settle down and do as I was told? I’d done as I was told, I’d worked hard and it was still taken away from me. I wanted to pursue a dream. This,” he adds, waving his arm in the direction of the three boxes, “is not just about native Americans.”

No. It’s about a boy who wasn’t expected to go far, an adventurer, who grew up and travelled to the other side of the world and found his role models. For further information about Andrew Hogarth’s books and photography, visit www.andrewhogarthpublishing.com

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.