National Library of Australia Card and ISBN 0 646 041525

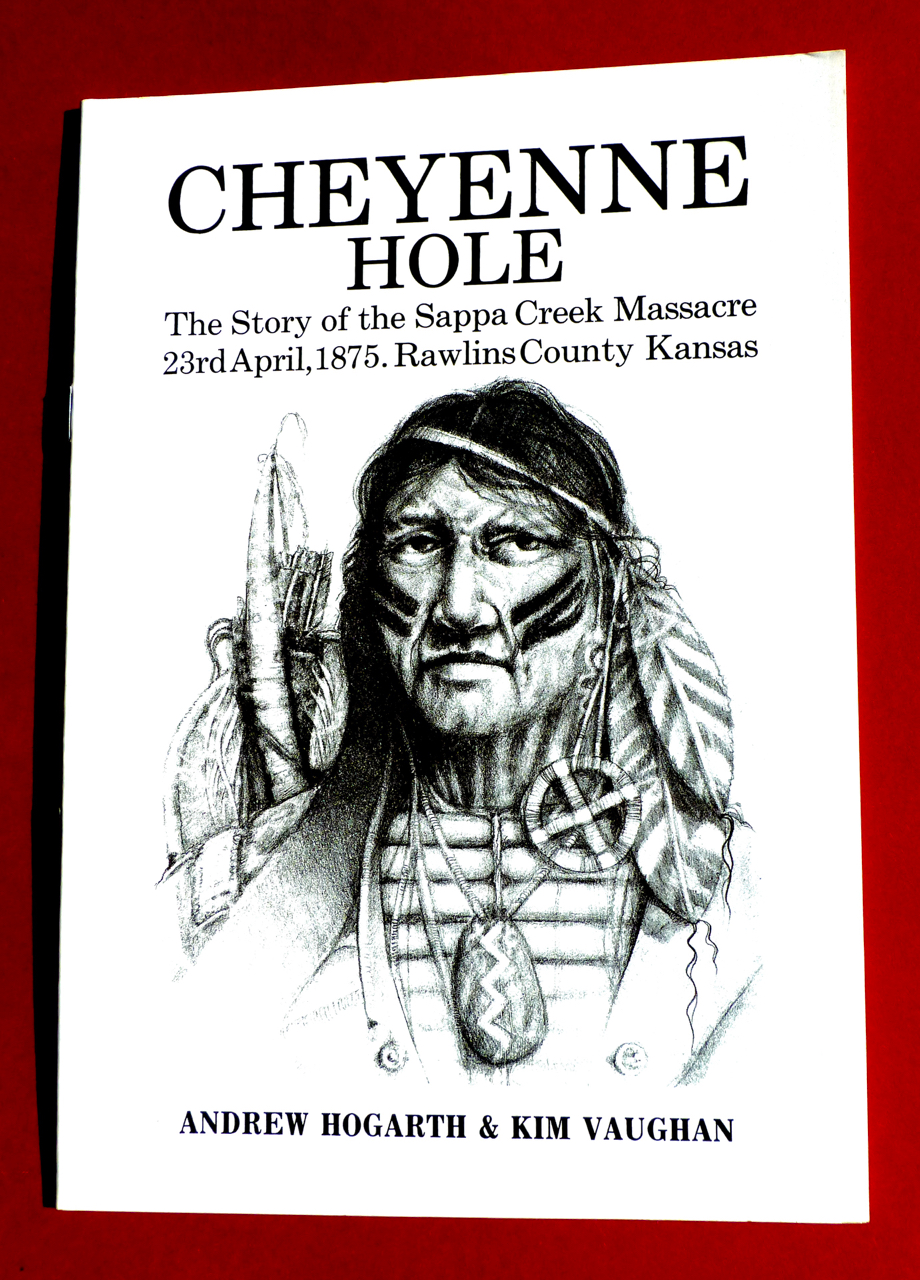

The story of the Sappa Creek Massacre, 23rd April, 1875. Based on oral history as told by Southern Cheyenne John Sipes Jr. Hogarth and Vaughan have investigated the Indian version of the massacre using original source material including that of the late Mari Sandoz’s work. This story challenges the commonly recorded version of the massacre based on the military report of the officer in charge, Second Lt. Austin Henley. The 24 page booklet includes photographs of the site, computer maps of the area and the evolution of the incident. Includes excellent sketches of native people by Australian artist Paul Farley.

Author’s Comments

History is perhaps only the reality of the writer, although the basis may be factual it is how those facts are interpreted which determines how the reader will learn about the past. The broad philosophical base of a particular society immediately slants the interpretation of the facts. This idea extends to the relative value of the forms historical information can take. What holds greater weight, the written word or the spoken word? Ultimately it depends on the society in which you live. Both of these ideas are relevant to the story of the Sappa Creek Massacre.

The Sappa Creek Massacre took place in Kansas on the 23rd April, 1875 and since that time rumour rather than controversy has persisted about what actually took place on that cool, grey morning. Material on the happenings at Sappa Creek is scarce. The majority of historians who have written excellent accounts of the Southern Plains Indian Wars of the 1860?s and 1870?s offer little that elucidates the situation, tending to use little more than a short paragraph to describe the death of Medicine Arrow, the victory of Lieutenant Austin Henley and I the unfathomable and brutal massacre of women and children. On close examination of the available information however and coupled with faith in the importance of both oral history and the written word two very different accounts of the Sappa Creek Massacre emerge.

The view most commonly taken by historians is that of the dominant society of the time. This point of view has as its basis the belief in the superiority of the written word and in particular the sanctity of a written military report, that is, the official military report filed three days after the massacre by Lieutenant Austin Henley. The accounts of influential participants of the battle such as Scout Homer W. Wheeler have also shaped this view. With the advantage of perspective that time away from the incident gives the historian and a broad general knowledge of both white and Indian history of the time close reading of the available accounts raises many questions.

Questions such as: (a) How many people both white and Indian were involved? (b) Why is Lieutenant Henley’s report not consistent with the physical conditions of the land and the stated number of soldiers? (c) Who in reality was in charge of the battle? (d) Why did the battle take place at all when the presence of Medicine Arrow, the keeper of the Sacred Arrows, would have undoubtedly led the Cheyenne to seek a peaceful solution.

There are also many other questions. The commonly reported view is also much modified and in some cases totally discounted by the Southern Cheyenne oral tradition, the work of historian Mari Sandoz, accounts of local settlers in the area soon after the battle and later local historians such as Doc Wimer and E. S. Sutton. The work of Mari Sandoz in particular is important in that she was a native of the plains area and that she achieved what so few have managed in being taken into the confidence of the Cheyenne Nation. Mari Sandoz met and spoke with a number of survivors of the Sappa Creek Massacre during her many visits to the reservations. The availability to today’s historians of accounts from both view points leads to the conclusion that the long held view of the battle is indeed open to debate.

During the summer of 1990 I located the Sappa Creek Massacre site in northwestern Kansas with the assistance of the curators from The Last Indian Raid Museum, Oberlin and the Rawlins County Museum, Atwood. The site is located ten miles south of Atwood on land owned by Mr Larry Curtin and family. No monument or marker is established at this historical site. State maps and tourist brochures of the region fail to mention the events that took place in this area one hundred and twenty-five years ago. The discovery of the Sappa Creek site was a personal highlight in my travels throughout the Plains. The area as shown in the photographs has changed little since 1875 when compared with historic descriptions of the area. Perhaps the most significant change is that there is many more trees today. Photographs, I believe are a good adjunct to the written word.

In closing I would like to thank the following people whose help and enthusiasm was most welcomed when I was researching material for this book: Fonda Farr, Last Indian Raid Museum Kansas; John Sipes, Southern Cheyenne Historian; Caroline Sandoz-Pifer, Gordon, Nebraska; Lyn Beideck-Porn, Nebraska University Archives; Patrick J. Fraker, Colorado Historical Society and Stuart L. Bulter, National Archives, Washington D.C. The book is dedicated to the indomitable spirit of the Cheyenne Nation and to the memory of Old Cheyenne Woman, a survivor of the massacres at Sand Creek, Sappa Creek, Fort Robinson and a time of rapid and often brutal change in the latter half of the nineteenth century.

Andrew Hogarth, 6th November, 1991.

@ COPYRIGHT 1991, Andrew Hogarth. First published 1991 Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, by Andrew Hogarth. All rights reserved. Art design: Andrew Hogarth. Map Graphics: Graham Carney. Front Cover: Cheyenne Dog Soldier and contents illustrations by Paul W. Farley. This booklet is sold subject to the condition that it is not to be reproduced either in the whole or in part, stored in retrieval system or transmitted in any form without the prior permission of the author and publisher.

Chapter 1. The Buffalo War

The traditional homeland of the Southern Cheyenne and Southern Arapaho covered eastern Colorado and western Kansas. The great southern buffalo herd estimated to number up to twelve million (1) provided a rich source of food, clothing and implements. The buffalo also played an integral role in Plains Indian culture. The traditional and nomadic lifestyle of the Southern Cheyenne and Southern Arapaho remained relatively undisturbed until the early 1860?s.

The 1860?s witnessed a strengthening in the immigrant push for land as immigrants pushed West ill unprecedented numbers. The lure of land and mineral wealth fired the imagination of a generation. This push West, while relieving growing economic problems in the East, presented the American government with a series of new dilemmas. The government, with the support of wealthy eastern industrialists, saw the domination and settlement of this land as their right but were confronted with the problem of how to protect its citizens from attack by the Plains Indians.

On a larger scale, the American government felt itself to be morally and economically bound to subdue the Indians. To achieve control of the Indian population and hence the West, the government favoured the policy of segregating the Indians from their land base and the white settlers by the formation of reservations and the forced settlement of the Indians. Little thought was given to the areas in which the reservations were to be established and the mix of tribes forced to share them.

The years 1864-1869 saw a period of bitter fighting between the United States army and the Southern Cheyenne. The indiscriminate attack on the peaceful Cheyenne village of Chief Black Kettle at Sand Creek in 1864 and the consequent massacre of one hundred and thirty- seven men, women and children set the tone of Indian-White relation- ships for the next decade. In the autumn of 1868 General Philip Sheridan received orders from Washington to extend his initiative against the Southern Cheyenne into the winter months.

The immediate result of this directive was the attack on Black Kettle’s village on the Washita River in Indian Territory. This attack clearly signalled the aggressive intentions of the American government and their willingness to disregard the terms of the Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867. The attack also caused much concern amongst the Southern Cheyenne with some bands claiming that a few young warriors had instigated this attack.

The Washita River incident divided the Southern Cheyenne into two main groups. Some bands accepted the inevitability of surrender and reservation life while the warrior societies and in particular the Dog Soldier society resolved to stay off the reservations and ultimately move north to join the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne. The defeat of the Dog Soldiers in 1869 saw the plains of Eastern Colorado and Western Kansas virtually free of an Indian population.

By 1870, the great southern buffalo herd was a source of growing concern for both reservation and non-reservation Indians. The immigrant push west, the consequent settlement of the land and the construction of the Kansas Pacific and Santa Fe railroads effectively diminished the buffalo range and numbers began to decline. The sport of buffalo hunting was popular across all levels of American society and attracted a number of wealthy European sportsmen.

The herd also provided an abundant food supply for the army, railroad workers and impoverished settlers. The Indians viewed the whiteman’s use and wastage of the buffalo with alarm. The buffalo was the major food source for the Indian and the terms of the Medicine Lodge Treaty allowed the Indians off the reservations for seasonal hunts providing the buffalo remained in sufficient numbers to justify these hunts. The Indians relied heavily on the hunts to supplement their paltry government rations.

In 1870 the economy in buffalo hides began in earnest. Buffalo hide provided an effective and economic source of leather for the manufacturing sector in the industrial East. The demand for buffalo hide was such that in the years 1872-1874 4,373,730 buffalo were killed for rail exports alone. (2) The rapid decimation of the great southern buffalo herd set the scene for an inevitable clash between the Indians and the United States government.

General Philip Sheridan applauded the work of the buffalo hunters. His agenda for the pacification of the Indians, sought to make the Indian a total dependant or ward of the government. Sheridan chose to ignore the questionable ethics and legal status of the majority of the buffalo hunters, he instead viewed them as his allies in “destroying the Indians commissary; and it is a well known fact that an army losing its base of supplies is placed at a great disadvantage.” (3)

The wholesale slaughter of the buffalo and the hunters move deep into Indian land south of the Arkansas River and then south again of the Cimarron River led the Indians and buffalo hunters into direct confrontation. This uneasy situation was further accentuated by the illegal trade in stolen Indian and ranchers horses and the sale of whisky which was reputably more freely avail- able than good water. Deemed adequate rations and access to an alternative though diminishing food source the Indians had no choice but to fight.

With the large number of buffalo-hunting outfits moving into Indian hunting grounds south of the Cimarron River, a base camp was established at Adobe Walls on the South Canadian River in 1874. The establishment of this camp was an arrogant gesture on the part of the buffalo hunters which was acquiesced with by the army. This action allowed only one interpretation of the United States government’s attitude toward the Indian. The treaty of Medicine Lodge had become meaningless.

Chapter 2. Cheyenne Resistance

On June 1874, a large war party of Southern Cheyenne, Kiowa and Comanche attacked the settlement of twenty-nine hunters at Adobe Walls. This attack was the last incident that could be considered an organised plan of the Plains Indian Confederacy. The concept of a Plains Confederacy was in fact quite alien to the Indians traditional lifestyle and the United States government gave more credit to this idea than what actually existed.

The battle of Adobe Walls lasted three days and resulted in the defeat of the Indians. The disparate number of twenty-nine hunters to seven hundred Indians demonstrates the effectiveness of the Sharps rifle and the buffalo hunters skill in its operation. Austin Heneley, the inexperienced second lieutenant who was to figure so prominently in the Sappa Creek massacre was briefly introduced to plains warfare at Adobe Walls as part of Lieutenant Baldwin’s relief party.

After their defeat at Adobe Walls, the Southern Cheyenne began an indiscriminate campaign of destruction and killing against the United States government. “On July 21, the order came from Sheridan’s headquarters to carry out active military operations to punish the hostiles, even to pursuing them onto the reservations:”(4) As a result of this order five columns numbering three thousand troops (5) converged on the Plains. The final subjugation of the Southern Plains tribes had been decided but the carriage of this action remained firmly in the control of individual commanders. Destitution in terms of food, clothing, shelter, horses and arms facilitated the army in their quest.

The forced and relentless campaign against the Indian was not wholly supported by the white community. The army and in particular Generals Sherman and Sheridan, came under heavy criticism from the eastern activists for their brutal methods and indiscriminate killing of women and children. The killing of five members of the German family and the capture of the four youngest daughters by War Chief Medicine Water in September 1874 did little to advance the already desperate Indian cause. Instead, it gave the army’s campaign the stamp of legitimacy and even respectability. General Sheridan used it effectively to silence the eastern critics.

The burial detail for the German family under the leadership of Second Lieutenant Christian Hewitt provided the press with a sensational story to promote anti-Indian sentiment. No one questioned the German family’s right to be in the area or their ignorance in undertaking such a journey at this time. The German family were innocently involved in what became a highly emotive affair and were tragically manipulated by both the Indians and the army.

The attack on Chief Grey Beard’s village on November 8th, 1874 by Lieutenant Frank Baldwin and his small force of men secured the release of the two youngest German girls, Juliana and Adelaide. It also established the fact that the Cheyenne were poorly armed and bereft of ammunition. The campaign was in fact so one-sided that General Sherman ordered his troops to “ease down on the parties hostile at present.” (6) The attack on Grey Beard’s village forced the Southern Cheyenne onto the Staked Plains to avoid the army and decide on a course of action. Of particular concern was the fate of the Mahotse or Sacred Arrows.

The Sacred Arrows are objects central to Cheyenne religious belief and in essence, their existence. A loose alliance formed through necessity on the Staked Plains with leaders such as Medicine Arrow, Sand Hill, Grey Beard, Medicine Water, White Antelope and Stone Calf gathered to determine the fate of the Sacred Arrows and the more immediate destiny of their people.

It was agreed that Medicine Arrow, Keeper of the Sacred Arrows, would move north under the protection of eighteen warriors from the Bowstring Warrior Society and seek refuge with the Northern Cheyenne. (7) The Cheyenne people may succumb to white domination but while the Sacred Arrows were safe the spirit of the Cheyenne Nation would survive. In a fashion typical of the Plains Indian individualism, some bands resolved to move north in small parties in an attempt to avoid detection while other leaders decided to surrender at the Darlington Agency. The two elder German girls, Catherine and Sophia, were released by the Cheyenne at the beginning of March 1875.

The surrender of Grey Beard, Stone Calf, Medicine Water and other leaders soon after and the inappropriate heavy-handedness with which they were treated sparked the incident which directly preceded the Sappa Creek Massacre and occasioned Second Lieutenant Austin Henely to be in the field. The German sisters were released in an attempt to negotiate favourable terms of surrender but in sharp contrast to being used as a measure of good faith the German sisters helped seal the fate of thirty-three Cheyenne warriors.

Not content with their release the sisters were used to identify prominent Cheyenne warriors and so assist ill the army’s insidious campaign to destroy the Cheyenne Nation. Thirty-three Cheyenne warriors including one woman were selected from a line-up and destined for imprisonment in Florida. During the attempt to shackle them, a young warrior, Black Horse, effected his escape. In the fight that followed over two hundred people escaped to the sand hills across the North Canadian River.

The Sand Hill fight lasted throughout the day. Despite their lack of arms and most certainly with the advantage of the terrain the Cheyenne survived the army’s use of the gatling gun with only six dead. (8) During the night an est1mated two hundred and fifty people (9) escaped under the guidance of Bad Heart. Some of these people under the leadership of Sand Hill, Turkey Wailing and Black Horse moved northwest from the Darlington Agency to join Medicine Arrow’s small band.

Chapter 3. The Flight North

A number of historians have denied that Medicine Arrow was present at Sappa Creek. It is perhaps too quick an assumption to believe that the Sacred Arrow Keeper would have totally alienated himself from his people in his move north. While the protection of the Sacred Arrows was of utmost importance, the compassionate aspect of the spiritual leader led Medicine Arrow to wait north of the Washita River (10) to ascertain the fate of the surrendering Cheyenne bands.

At the close of the Red River War the army considered that there were two types of Indians. Those that were considered “peaceful” and accepted reservation life, while those considered “hostile” refused to surrender or had escaped from the reservation.

In direct response to the Sand Hill fight and in an attempt to recapture the fugitive Southern Cheyenne, Second Lieutenant Austin Henley and forty men of H Company, Sixth Cavalry were ordered into the field. On the morning of April 19th, 1875 Second Lieutenant Henely and his men accompanied by Second Lieutenant Christian Hewitt, Surgeon F. H. Atkins and post trader Homer Wheeler left Fort Wallace with orders to round up the hostiles.

On the fifth morning out of Fort Wallace Lieutenant Heneley and his men encountered and attacked a largely peaceful village on Sappa Creek. A number of factors in the lead up to the fight played a decisive role in the way the battle was fought and ultimately the outcome.

Both Henley and Hewitt were inexperienced frontiersmen and relatively junior officers. Austin Henley’s previous experience of the Southern Plains Indian was at Adobe Walls in 1874 as part of Baldwin’s relief party. The fight was virtually over when the relief party arrived so Henely saw little action.

Christian Hewitt’s unfortunate introduction and extent of experience was as leader of the German family burial detail in 1874. It could be assumed that Hewitt’s view of the Southern Cheyenne was undoubtedly biased by his experience. Both men knew little of the area encompassing northwestern Kansas and their leadership talents were relatively untested.

Post trader Homer Wheeler was an experienced frontiersman and had spent a number of years in northwestern Kansas. He was an experienced army scout having participated in the Beecher’s Island siege in 1868. His dealings and attitude toward the Southern Cheyenne were indeed mixed.

His motive for readily volunteering to join Henley was not entirely altruistic as some accounts would suggest. In fact by his own admission, he perceived Heneley’s mission as a direct response to trouble his peers had encountered in trying to round up cattle near Punished Women’s Fork. (II) His own herd had been stolen from a number of times.

Far from being modest, Wheeler was an ambitious and verbose man as witnessed by his memoirs. His influence on the inexperienced Henley should not be underestimated. Four days passed from the time Second Lieutenant Henely received his orders at Fort Lyons, Colorado until he was in the field. Little of that time it would seem was spent in detailing a plan of search.

Three days after an inauspicious start Henley decided on a northeast course to the North Beaver Creek as he believed the Indians would collect there for the purpose of hunting. (12) His actions two days later would also indicate the lack of a detailed and formalised plan. On the 22nd April Second Lieutenant Henley and his party met a group of buffalo hunters heading back to Fort Wallace. An estimated twenty-three to twenty-six hunters were in the camp. (13)

Three of their colleagues, Dan Brown, Charley Lucas and Bob Canfield had been recently killed by the Southern Cheyenne. (14) Hank Campbell informed Henley that there were Southern Cheyenne camped on the north fork of the Sappa. (15) Second Lieutenant Henley’s report states that three buffalo hunters, Campbell, Schroeder and Scrack volunteered as scouts.

Considering the recent circumstances and very generally the type of personalities the buffalo hunting outfits attracted it is naive to imagine that only three hunters accompanied Henley and his men. Reports indicate that at least twenty buffalo hunters took part in the Sappa Creek Massacre. (16) Whether Henley sanctioned the buffalo hunters accompaniment is not known. It is however, indicative of the strength of his leadership as civilian participation m army battles was unacceptable.

It is this lack of authorative leadership that distinguishes many incidents of the Sappa Creek Massacre. In the early morning of 23rd April, 1875 Second Lieutenant Henley, his men and over twenty civilians attacked the village of twelve lodges (17) located on the Sappa. Henley’s orders were to round up the hostiles and bring prisoners.

His report, however, clearly states his order “to kill the herders”. (18) This order certainly excluded a peaceable solution. It appears that Henley knew the direction the encounter would take and at this early time had possibly already lost control of the situation.

The troops and the buffalo hunters crossed the creek independently of one another. The buffalo hunters took up positions on the bluffs some eighty metres north and east of the village. (19) Henley and his men made a precarious and finally successful attempt to cross the swollen, fast running stream (20) by which time the element of surprise was lost. Henley’s choice of a southeast attack was prejudiced by the steep marshy bank.

Henley effectively lost control of the encounter by his poor choice of crossing, lack of knowledge of the topography and miscalculation of the size of the village. On first appraisal the village appeared to be comprised of twelve lodges, which would have housed approximately sixty people. However, a number of sleeping holes were cut into the bank below the semi- circle of the bluffs to accommodate the destitute Black Horse and Sand Hill people.

Chapter 4. The Massacre

Cheyenne oral history places at least one hundred people in the village. (21) Medicine Arrow bound by the obligations of his holy office as Arrow Keeper attempted to seek a peaceful parley but was not given a fair chance. The hunters had positioned and settled themselves on the bluffs before Henley’s arrival at the southeast end of the arc.

The hunters wasted no time in opening fire into the village. Their lethality was ensured by two factors. The Cheyenne did not seek escape or try to retaliate while the Arrow Keeper attempted to parley, (22) so immobilising them within an already comfortable Sharps rifle range.

Secondly, the Sharps rifle was well refined and was capable of killing a buffalo with “one bullet if the bullet was properly placed.” (23) The hunters killed forty people (24) in the short opening engagement. Henley’s unsuccessful approach from the southeast resulted in the death of two soldiers. (25)

Despite the gunfire from the buffalo hunters Medicine Arrow attempted to parley going “through the fog and smoke and bullets that did not stop coming, on towards the soldier chief waiting from a higher place.” (26)

Only when Medicine Arrow fell did the Cheyenne take up arms to protect themselves and attempt escape. The soldiers too attempted to better protect themselves by moving back to the creek to regroup and then take up a holding position southwest of the village. (27)

Those Indians left alive in the village sought refuge with those already in the main sleeping hole. Escape from this hole, later named Cheyenne Hole, became impossible as the hunters and soldiers directed fire into it. poorly equipped with weapons and ammunition the Cheyenne attempted to surrender a number of times. (28)

Their attempts were ignored. By this time the occupants of the hole were mainly women and children. The depth of the hole, some eight to ten feet (29) can only inadequately relate the desperation of the Cheyenne. The major part of the engagement, an estimated two and a half hours, was directed at trying to dislodge the Indians from the main sleeping hole.

Not content with the atrocities already committed and when it was determined that there was no further threat from Indian fire, the hunters proceeded to dig out and brutally murder those who had survived the three-hour fight.

Henley ordered the village, camp equipage and ammunition to be burnt. A number of Cheyenne, including children were also thrown into the fire while still alive. (30) Whether this action was intentional will never be known but despite the motive it is unforgivable.

In the three-hour battle Henley injudiciously divided his command so that only twenty to thirty soldiers took actual part in the battle. Despite this relatively small number the official report stated twenty-seven killed, nineteen warriors and eight women and children. (31) “Henley took no prisoners and killed more Cheyenne than the combined columns had during the winter campaign of 1874-75?. (32)

Cheyenne oral history and reports of civilians in the area a few days after put the Indian dead at between seventy to eighty. (33) There are other inconsistencies and eccentricities in Henley’s report that was filed three days after the engagement. Henley dismisses the Cheyenne attempt to parley cursorily and was in fact already prepared to fight. He reports a chief’s approach and hand gestures when in reality it is doubtful that Medicine Arrow succeeded in getting that close to Henley before his death.

Henley states that he “threw some of the arms into the fire, destroying also a quantity of ammunition”. (34) This was routine practice by the army but an extraordinary small number of eight weapons was finally turned in at Fort Wallace. It is puzzling that an amount of ammunition was also destroyed when it was generally known that the Southern Cheyenne were poorly armed.

Henley’s report in general does not tally with the physical evidence. The Sappa Creek Massacre was the last engagement in the Red River War. It was an event that the Southern Cheyenne still speak little of today. It is ironical that a poorly investigated and inaccurate report is filed in the National Archives and virtually forgotten while the Southern Cheyenne still acutely feel the loss of so many women and children.

Investigation of the massacre by Henley’s superiors was unacceptable as the furore it would have created would have jeopardised the army’s plan for the final subjugation of the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne. Despite the United States government’s attempt to destroy the Southern Cheyenne Nation the Mahuts or Sacred Arrows were escorted safely from the Sappa Creek battlefield and so the spirit of the people survived.

Cheyenne Hole Notes

1 Haley, The Buffalo War, pp20-21.

2 Haley Ibid, p22.

3 Hedren, The Great Sioux War 1876-77, p103.

4 Andrist, The Long Death, p190.

5 Andrist, Ibid, p192.

6 Andrist, Ibid, p197.

7 Sipes, Letter, Sipes to Hogarth.

8 Sandoz, Cheyenne Autumn, p8S.

9 Sandoz, Ibid,p89.

10 Stauffer, Mari Sandoz Story Catcher of the Plains, p178.

11 Wheeler, Buffalo Days, p99.

12 Henley, Official Military Report, 26th April 1875 p2.

13 Sandoz, The Buffalo Hunters, p239. Sutton, “Sappa-Meaning Black Hole”, pp6-7.

14 Sutton, Ibid, p7,

15 Henley, Op. Cit., p2. Sutton, Ibid, p6.

16 Sandoz, Cheyenne Autumn, p94. Letter, Wimer to Sandoz, 15th November, 1949. West, “The Battle of Sappa Creek” in Kansas Historical Quarterly, 34. 1949 p161. Sutton, Op.Cit. pp6-7. (Buffalo hunters at Sappa Creek:- Joe Brown, N. M. Kress, Smokey Johnson, Stowell Kilburn, Alexander, Van Meter brothers. Sol Reece, Dan Dimmit, Joe Rutledge, Hank Campbell, Charles Schroeder and Samuel B. Sarch. Old man Grout who was two miles below the fight counted over twenty piles of Sharps empty cartridge cases on the ridge overlooking Cheyenne Hole, with four to twenty-five cases in each pile.)

17 Henley, Op. Cit., p6.

18 Henley, Ibid, p3.

19 Letter, Wimer to Sandoz, Op. Cit. Sutton, Op. Cit., p8. (John Koontz who settled on the land in 1879 stated that “we could tell the position of the buffalo hunters and the soldiers by the empty cartridges”. Hunters using Sharps were east and north of the Indians, soldiers using carbines were south west. “From the amount of empty shells, there were possibly two dozen hunters or cowboys in the fight.”)

20 Wheeler, Op. Cit., p105. Hewitt, “Diary”. Henely, Op. Cit., p3.

21 Sipes, Op. Cit.

22 Sipes, Ibid. Sandoz, Cheyenne Autumn, p90.

23 Rywell, Sharps Rifle, p12.

24 Herdon, Kansas Nonpareil, July 18th, 193- Street, “Cheyenne Indian Massacre Middle Fork of the Sappa “in Kansas Historical Society, 10, 1907-8, p2.

25 Henley, Op. Cit., p5.

26 Sandoz, Cheyenne Autumn, p90.

27 Letter, Wimer to Sandoz, Op. Cit.

28 Sandoz, Cheyenne Autumn, p92.

29 Letter, Wimer to Sandoz, Op. Cit.

30 Sipes, Op. Cit. Sandoz, Cheyenne Autumn, p93. West, Op. Cit., p163.

31 Henley, Op. Cit., p6.

32 Berthrong, The Southern Cheyenne, p404.

33 Herdon, Kansas Nonpareil, Op. Cit. Street, Op. Cit., p3. Cowboy John Love, of Oberlin, Kansas, visited the battlefield two days after the massacre. He counted the bodies of 28 Indian warriors lying where they had fallen. Squaws (women) and children and possibly some of the braves had been thrown into a gulch and covered. John Sipes jnr, whose knowledge of Cheyenne oral history given to him by Pete Birdchief (1899- 1986) made him one of few authorities on the massacre. Birdchief, of Oklahoma, knew survivors and said the village was mainly occupied by women, children and elders.

34 Henley, Op. Cit., p6.