The Open Road

by Matt Ody

Australian Journey Magazine, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia, 2013.

Storyteller and photographer Andrew Hogarth survived his turbulent upbringing to find his calling while documenting the truth about what happened to the North American Indians

When photographer Andrew Hogarth returned last year to the North American Great Plains for the 16th time since 1981, it was a bitter-sweet experience.

He planned to make it his last visit after 30 years of travel to the area seeking and documenting the truth about what happened during the Great Plains Indian Wars from 1854-1890.

The stories he uncovered are revealed in his books, musical lyrics and perhaps most significantly, photography.

Thirty years of photographic film – 880 negative images culled from thousands – have been preserved in three rosewood boxes from his 17 field trips from 1981-2011.

Many of these images are internationally renowned and tell the story not just of the plight of the North American Indians, but also of the Scottish-born, Australian-based photographer’s own life journey.

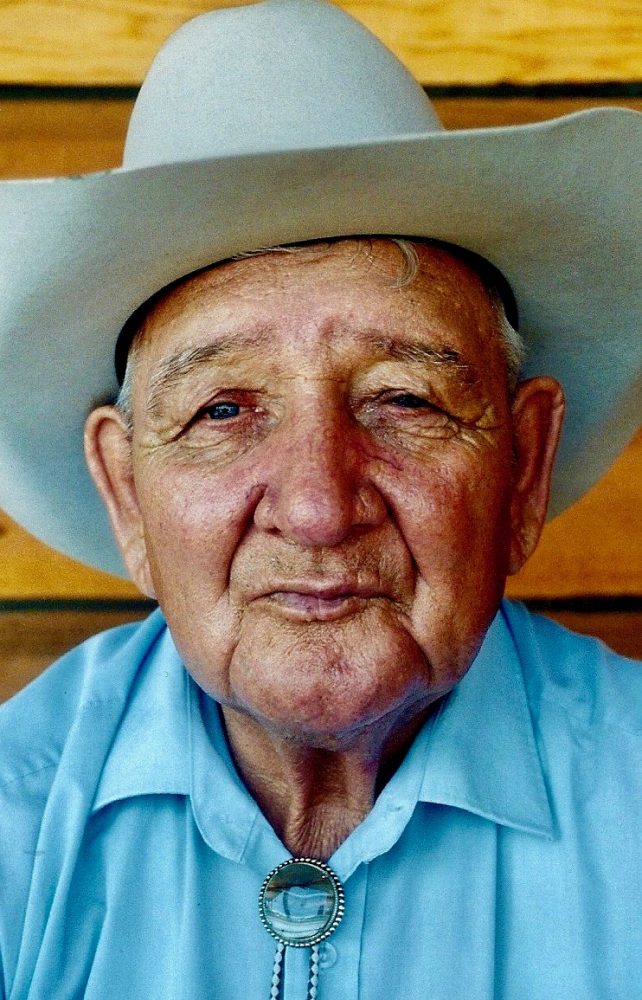

Percy War Cloud Edwards Plains Indian Museum Powwow Wyoming 2011

Hogarth’s achievements as a photographer and storyteller of the North American Great Plains has given his life a purpose and meaning that was absent, as a boy on a housing estate on the outskirts of Edinburgh, Scotland.

His fascination with North American history started as a love of television westerns including Bronco Lane with Ty Hardin, Maverick with James Gardner and Rawhide with Clint Eastwood.

However, it was the 1970 movie Soldier Blue by director Ralph Nelson starring Candice Bergman and Peter Strauss, which depicted the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado Territory of approximately 134 members of the Southern Cheyenne and Southern Arapaho tribes at Sand Creek, Colorado, by Colonel John Milton Chivington and his 650 Colorado Volunteers, “that really turned the switch on”, says Hogarth.

“It was the most savage film. The American Government had tried to suppress it.”

Sand Creek Massacre Site Colorado 2011

Custer Battlefield Trading Post Crow Agency Montana 2011

Native Lands Exhibition Graphis Fine Art Gallery Sydney Woollarha 1994

By 1981 the history of the North American Indians had become his passion. The pursuit of knowledge and truth, and the documentation of his discoveries would sustain and fulfil Hogarth over the next 30 years.

“My visit in 2011 allowed me one last time to take in the interesting history of the last Plains Indian Wars on the American Continent regarding the Lakota-Sioux Nation and the Cheyenne Nation against the US Army,” Hogarth says.

Hogarth emigrated to New Zealand when he was 22, and had periods living in Australia and Scotland before settling in Sydney in 1982.

He was employed by News Ltd in the Graphic Reproduction Department until the mid-1990s, but continually poured his money back into his publishing and photography projects, often selling the books from the back of his hire car during his travels.

He has participated in many exhibitions since 1994, both here and in America. In 1994, his photographic collection Native Lands: The West of the American Indian debuted as a solo exhibition in Woollahra, Sydney.

The same year Hogarth left full time employment to establish his work in the United States of America. Powwow: Native American Celebration photographic exhibition was shown nationally in the United States of America and Canada, and later in Australia.

Hogarth says he is proud of what he’s achieved and of what he’s overcome to get to where he is now.

“I was one of only 14 people in the world chosen for a national tour of America. It was like winning an artistic gold medal,” he says.

“It felt like a terrific achievement for a little street kid from Magdalene Gardens (housing estate).

Hogarth has doggedly pursued the life he wanted – a life driven by passion and devoted to learning the truth and storytelling.

Powwow: Native American Celebration Graphis Gallery Sydney 1997

Jonathan Maxwell Beartusk Little Bighorn Battlefield Montana 2011

Bear Butte Mountain South Dakota 2011

He says his visit to the Great Plains for the last time in 2011 was an important and intensely personal experience, which included a visit to the Little Bighorn Battlefield in south-eastern Montana where he photographed Northern Cheyenne Solar Artist Jonathan Maxwell Beartusk at the Indian Memorial.

“Jonathan Maxwell Beartusk is a solar artist who uses a magnifying glass to burn old historical images of Plains Indian chiefs and warriors onto wood. We shot our classic image at the Indian Memorial on the Little Bighorn Battlefield in the summer of 2011.

“Later we spent time at the grave marker of his relative Chief Lame White Man located on the battlefield. Later that week I attended the Real Bird re-enactment held annually at Medicine Tail Coulee.

“This also was a sight to see with Indians and soldiers riding around firing guns at each other on the exact location of land that Custer and the Seventh Cavalry tried to cross over into the large Sioux and Cheyenne encampment.

Hogarth then travelled on to – and climbed – the sacred Bear Butte Mountain in South Dakota where the Cheyenne creation objects were brought to the people by the tribe’s prophet Sweet Medicine.

“I had climbed to the top with my wife Kim in 1989 but at the ripe old age of 61 this time was extra special with the mountain being an A-Grade Hike,” he says.

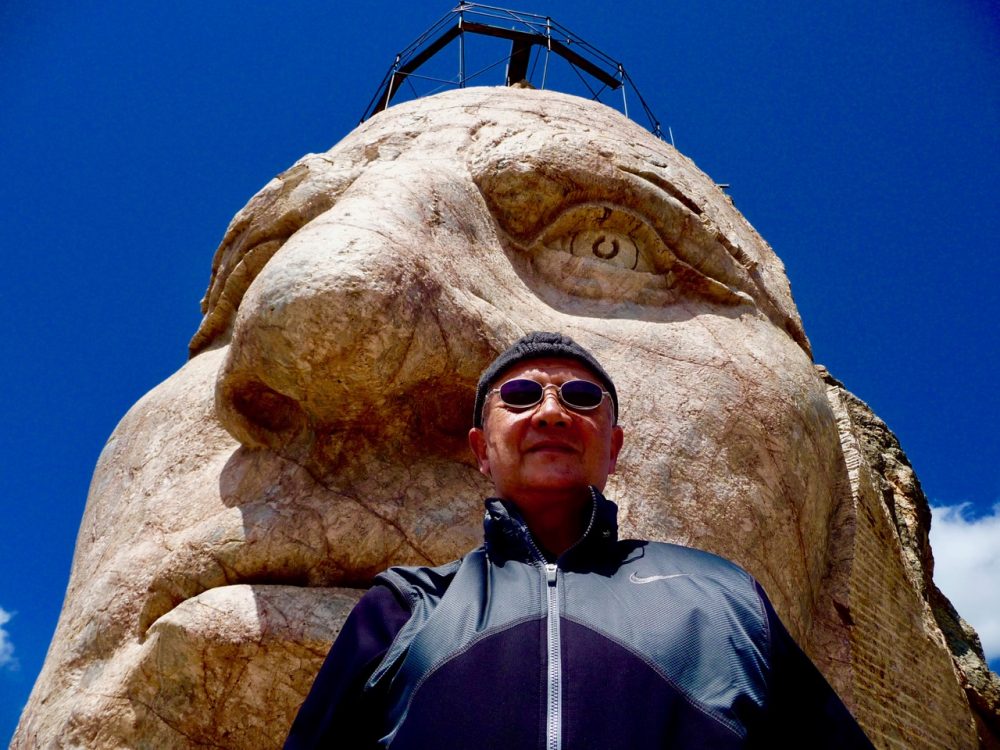

He also travelled to the top of Crazy Horse Mountain in the Black Hills of South Dakota.

“This gave me the opportunity to think back over the years when I arrived at the highway entrance of Crazy Horse in 1982 and walked up to the visitor’s centre where I met the man who would change my life, Lakota-Sioux Jack Little.”

Hogarth is proud to have met a handful of individuals who had direct contact with some of the main players in the Indian Wars of 1876-1877, up to Wounded Knee in 1890.

These include Lakota-Sioux Jack Little, a respected native American guide who would later take Hogarth up on the offer of publishing his autobiography, and Bill Groethe who Hogarth met in Rapid City, South Dakota in 1995.

In 1948, Groethe, now 88, photographed the last eight survivors from the Little Bighorn Battle in June, 1876. Black Elk was one of these old warriors.

Bill Groethe 1st Photo Store Rapid City South Dakota 2008

Caroline Sandoz Pifer and Kim Vaughan Sand Hills Nebraska 1992

In 1992 and 1999, Hogarth visited with Caroline Sandoz Pifer, the younger sister of author Mari Sandoz who wrote the book Crazy Horse: The Strange Man Of The Oglala’s.

In the beginning, Hogarth rarely photographed people, preferring to focus on recording 80-historical battle sites scattered across the Great Plains.

He says his aim was never to “become” a Native American Indian. He just wanted to tell their stories.

“I never wanted to become one of them or live with them in tepees. I didn’t want to be a Native American Indian. I’m Scottish-Australian and I was there as a storyteller – that’s what I do.”

On the 2011 trip, before returning to San Francisco and finally Australia, Hogarth travelled to the Rosebud Casino Powwow held annually on the Rosebud Reservation.

“Here I caught up with my friends Emily and Mike Ponyah and their six children. On the way back to Billings, Montana we all stopped at the site of the Wounded Knee Massacre on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota to pay our respects.

“Emily is part Lakota and part Scottish and grew up on the Pine Ridge Reservation with her grandmother who taught Emily many of the old style ways of beading.

“We then passed through the Badlands National Park and during a pit stop on the gravel road young Gracie came over to me and said that her mum and dad had spotted a Scottish Thistle growing at the side of the road.

“It may well be a touch corny but after 30 years on the open road recording stories about the people living on the land I enjoyed this symbolic touch.”

“It was a very personal journey.”

Jonathan Maxwell Beartusk Little Bighorn Montana 2011

The Great Plains: Little Bighorn to Wounded Knee

Andrew Hogarth is a native of Scotland, long time resident of Australia and a world traveller. Hogarth’s interest in Native American culture was ignited early in his youth and has led him to travel some 187,000 miles over thirty years throughout the northern and southern Great Plains region of the United States of America. His extensive fieldwork has resulted in three photographic collections and the publication of six books.

Having spent many Saturday afternoons of his childhood in the movie houses on Edinburgh’s Leith Walk watching westerns and having a fascination with the ubiquitous weekly western serials of that period, he was long captivated, intrigued and transported by the American West. The cowboys, pioneers and soldiers seemed brave and determined and the Indians were new, dangerous and exciting. Despite being idealistic and romantic these stories struck a deep resonance in him. The intimation that life could be so free and embrace such a different set of values from those of Hogarth’s surroundings was both powerful and seductive. The reality of the American West today while often poorly stereotyped is not so different from those early impressions. It is however far more nuanced.

The history of the American West is a recent one and very much part of the people today. It is a living entity that is felt rather than viewed, embraced rather than held at a detached distance. Ancestral lines are well remembered and very much part of the identity of each individual. Life is a celebration of the seemingly everyday, of family and community, of struggle and triumph played out against a larger than life landscape that combines quiet beauty, glorious majesty, endless skies, ancient grounds, recent history, relentless monotony and often unforgiving weather. The Great Plains reward the observant, the patient and will delight the curious but respectful.

Enlistedmen’s Monumement Little Bighorn Battlefield Montana 2009

The Playhouse Theatre Edinburgh Scotland

Devils Tower Wyoming 2008

Within in a matter of a few hours west coast city life is a distant memory and a journey in which you choose whether or not to surrender yourself to the embrace of the West is before you. The Great Plains is home to some of the most recognised and iconic American monuments – Mount Rushmore, Devil’s Tower and the Little Big Horn National Monument. An inevitable part of the western experience however the Plains can offer the visitor so much more beyond the usual tourist fare. Billings, Montana is a somewhat inauspicious place to begin a Great Plains journey. Montana’s largest city it straddles Interstate 90 greeting the visitor with an unpromising urban and industrial sprawl. The skyline proudly broadcasts the emblems of its biggest industry – oil. It is a pragmatic choice from which to begin as it offers frequent air services and importantly access to a good car. Friendly enough but not a place for lingering.

Shortly after leaving the industrial cityscape of Billings you are in the embrace of the undulating plains and an endless sky. The roads are good and the speed limit generous. The Little Bighorn Battlefield lies sixty miles southeast of Billings on Interstate 90. There are no services for the first fifty miles. Passing the towns of Hardin and Crow Agency a sense of quiet anticipation grows as you near one of America’s most tragic, celebrated and honoured sites. There is a just a glimpse of a different rhythm, an unfamiliar culture and a stillness pervades the air. The heat is dry and intense. Just off Interstate 90 but hidden well from view until you clear the unprepossessing turn-off from Highway 212 is the site of Custer’s infamous Last Stand.

Enlistedmen’s Monumement Little Bighorn Battlefield Montana 2009

Little Bighorn River Montana 2011

Real Bird Re-enactment Medicine Tail Coulee Little Bighorn Montana 2011

A vast 735 acre site administered by the National Park Service, the Little Bighorn Battlefield is considered one of the ten most memorable conflict sites in modern history. The starkness and remoteness of the site is striking even today. On the 25 and 26 June 1876 the Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho unleashed a highly skilled and cohesive attack on Custer’s 7th Cavalry. A decisive victory for the Plains Indians and an unthinkable defeat for a brash young nation and their dashing but imprudent Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer. Sadly after a long campaign to save their nomadic way of life, the victory was bittersweet with the US government intensifying its resolve to enforce reservation life.

A visit to the Little Bighorn Battlefield is a rite of passage for many and visitors today can share in many activities either as a participant or observer. In late June each year the Real Bird reenactment takes place at Medicine Tail Coulee on the Little Bighorn River. The river and bluffs above come alive with the sound of mock battle providing a haunting reminder of what Custer and his Cavalry faced as they tried to cross the river into the large Cheyenne and Lakota-Sioux encampment here. In contrast the Northern Cheyenne commemorate the anniversary of the Battle of the Little Bighorn by hosting a Spiritual Run in which the younger members of the tribe participate in a 36 mile relay from Deer Medicine Rocks, the site of Sitting Bull’s prophetic vision of victory over the US Army to the Indian Memorial on the battlefield. The celebration is one of unity and strength of spirit. What is often overlooked is that the Little Bighorn Battlefield holds direct and individual significance for people today such as Jonathan Maxwell Beartusk a direct descendent of Chief Lame White Man who lost his life during the fierce fighting and is honoured by one of the Indian markers located on the battlefield. Casualities of more recent conflicts are also quietly remembered in the gentle pine grove of the adjacent military cemetery.

Deer Medicine Rocks Montana 2011

Deer Medicine Rocks Montana 2011

Cheyenne Spiritual Run Little Bighorn Anniversary Montana 2011

The spirit of the West lies not just in the land and its history but in its people. From trading post porches to individual storytellers the narrative of the Great Plains is continually shaped and revealed through a strong tradition of oral history. The Custer Battlefield Trading Post is one of my favourite places for visiting with people. Located on Highway 212 just a short distance from the Little Bighorn Battlefield it is a meeting place for day to day business on the Plains – a crossroads of sorts where visiting is the custom. If you are in luck the opportunity to share in a story on the front porch is a memorable occasion. From ranchers, traders, historians, travellers and artists all share a love of the plains. Over the years Hogarth had the pleasure to spend time with people such as Arikara trader Emerson Chase whose ancestors scouted for the 7th Cavalry, Crow Tribal Historian Joe Medicine Crow an author, decorated World War II veteran and recipient of the US congressional medal and Margot Liberty distinguished anthropologist and author.

Emerson Chase Arikira Custer Battlefield Trading Post Montana 1995

Andrew Hogarth Bear Butte Mountain South Dakota 2011

Crow Fair Crow Agency Montana 2009

Summer on the Great Plains is a time of celebration. Powwows are an opportunity to gather together with family, friends and the community to celebrate life and culture through music, dance and costume. South eastern Montana is home to the Crow Nation. Their summer gathering, Crow Fair is an encampment of up to 1500 tepees bringing some 10,000 people together over five days and nights. Negotiating a gathering the size of Crow Fair can be daunting but the opportunity to see spectacular grand entry parades inter-tribal dances accompanied by the mesmerising sound of the drums, a horseback parade through the encampment and a great rodeo is well worth the effort. Smaller powwows and dances take place all across the Great Plains and most will welcome visitors with quiet curiosity and generosity of spirit. An invitation into camp is a privilege. Camp gatherings are often imbued with special spirit which strike a powerful and lasting impression of the interconnectedness of the people, their history and the land.

Interstate 90 Hardin Montana 2009

Crow Fair Parade Crow Agency Montana 2009

Grand Entry Crow Fair Crow Agency Montana 2009

Travelling east on Interstate 90 toward South Dakota a detour through the Big Horn Mountains Wyoming offers a peaceful respite from the plains. The gentle beauty of the scenic byways is cause for quiet contemplation a quality that the Big Horn Mountains has engendered in people for some 800 years.The largest Medicine Wheel in North America, part of the ancient spiritual landscape of the West testifies to this. The mountains are home to bear, sheep, mountain lion, moose and deer. It is a great place for moose spotting with very few trips unrewarded by the sight of these extraordinary creatures.

Bear Butte a lone igneous intrusion millions of years old, is a place of deep spiritual significance for the Cheyenne, Lakota and other Plains Indians. Off Highway 31 just outside Sturgis South Dakota, the mountain is open to all with a two mile trail leading to the summit affording excellent views to the Black Hills. The plain below is home to the buffalo. Cheyenne history considers it the place where the Creator gifted the prophet Sweet Medicine the four sacred arrows and teachings to guide his people.Lakota leaders Red Cloud, Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull sought personal vision here and in 1857 gathered to chart their course against the increasing intrusion of white settlement into the Black Hills. Bear Butte remains a place of individual pilgrimage with prayers represented by the tying of small tobacco bundles and colourful prayer cloths to the mountain’s foliage. It is also an active ceremonial meeting place.

Andrew Hogarth Crazy Horse Memorial Black Hills South Dakota 2011

Crazy Horse Memorial Black Hills South Dakota 2011

Crazy Horse Memorial Black Hills South Dakota 2011

The Black Hills of South Dakota offer the visitor a truly beautiful landscape to explore however they are not without controversy. Historically the Lakota considered the Black Hills sacred and have refused to accept compensation for their seizure. Today the Crazy Horse Memorial stirs strong feelings in both Indians and non-Indians alike – you either love it or hate it. The story of the memorial is one of vision, leadership, perseverance and hardship. Chief Henry Standing Bear initiated the project in 1929 commissioning east coast sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski to carve a memorial to the indomitable spirit of Oglala Lakota Crazy Horse. Carving commenced in 1948 and continues as a work in progress. Slowly a monumental Indian on horseback standing 563 feet high is emerging from the granite mountain. Supported by a good museum and galleries the site is well worth a visit.

Wounded Knee Massacre Gravesite Pine Ridge South Dakota 2011

Wounded Knee Massacre Gravesite Pine Ridge South Dakota 2011

Wounded Knee Massacre Gravesite Pine Ridge South Dakota 2011

Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation is a sad and desolate place. The memorial and mass gravesite of those killed in the infamous Wounded Knee massacre stands in quiet vigilance at the junction of Highways 27 and 28 just south of the town of Porcupine. The massacre of 298 Minniconjou and Hunkpapa Lakota in the fierce winter weather of December 1890 marked the end of the Indian Wars almost 400 years after the landing of Columbus. It is a place of quiet reflection, a little known event in our history of man’s inhumanity to man.

On leaving Wounded Knee, meditating on the shortness of our time on this planet and heading out across one of the world’s richest fossil beds that strange and ancient landscape of the Badlands, Hogarth is always reminded that the Great Plains is a special place, a place that defies simple definition. The land does not exist in isolation but is part of a unique relationship between those of the land, indigenous America and all aspects of nature that are synonymous with the North American continent. It is a place where the past, present and future is subtly blurred.

Chuck Cochran will never be blurred! Thanks for the memories!

Thanks for the beaded turtle Patti Douville!

Andrew’s Parting Note 3rd of January 2020: The Great Plains Northern road trip of 2011 was my fifteenth trip to the region over a period of twenty-nine years and for one last time I was able to enjoy the history and catch up with dear friends along the way. My initial Trek America three weeks road trip in 1981 was a “Southerner” as advertised in their brochure. I would make it back down to the southwest and Southern Great Plains in the summer of 2013 shortly after my operation in late 2012 making it a total of seventeen road trips in thirty-two years. With 200,000 on road miles under my belt I must say watching the sunrise and the sunset while moving at high speeds along Interstates and Highways was indeed a real treat to behold. Before catching my Delta domestic flight from Billings back to Salt Lake City and then on to San Francisco I spent time with the Ponyah family at the 4th of July weekend Rosebud Casino Powwow in South Dakota. On our way back north we passed through the Badlands National Park and during a pit stop young Gracie came over and handed me a Scottish Thistle that her mother Emily and father Mike had found growing at the side of the road. Call me sentimental but for an old Scottish refugee it was the nicest touch to say goodbye to the Northern Great Plains! Thanks Grace!

A beautiful Nebraska Sunset 2011

Camille Emily…..Grace Liam Mike Evan Kelly Ponyah 2011