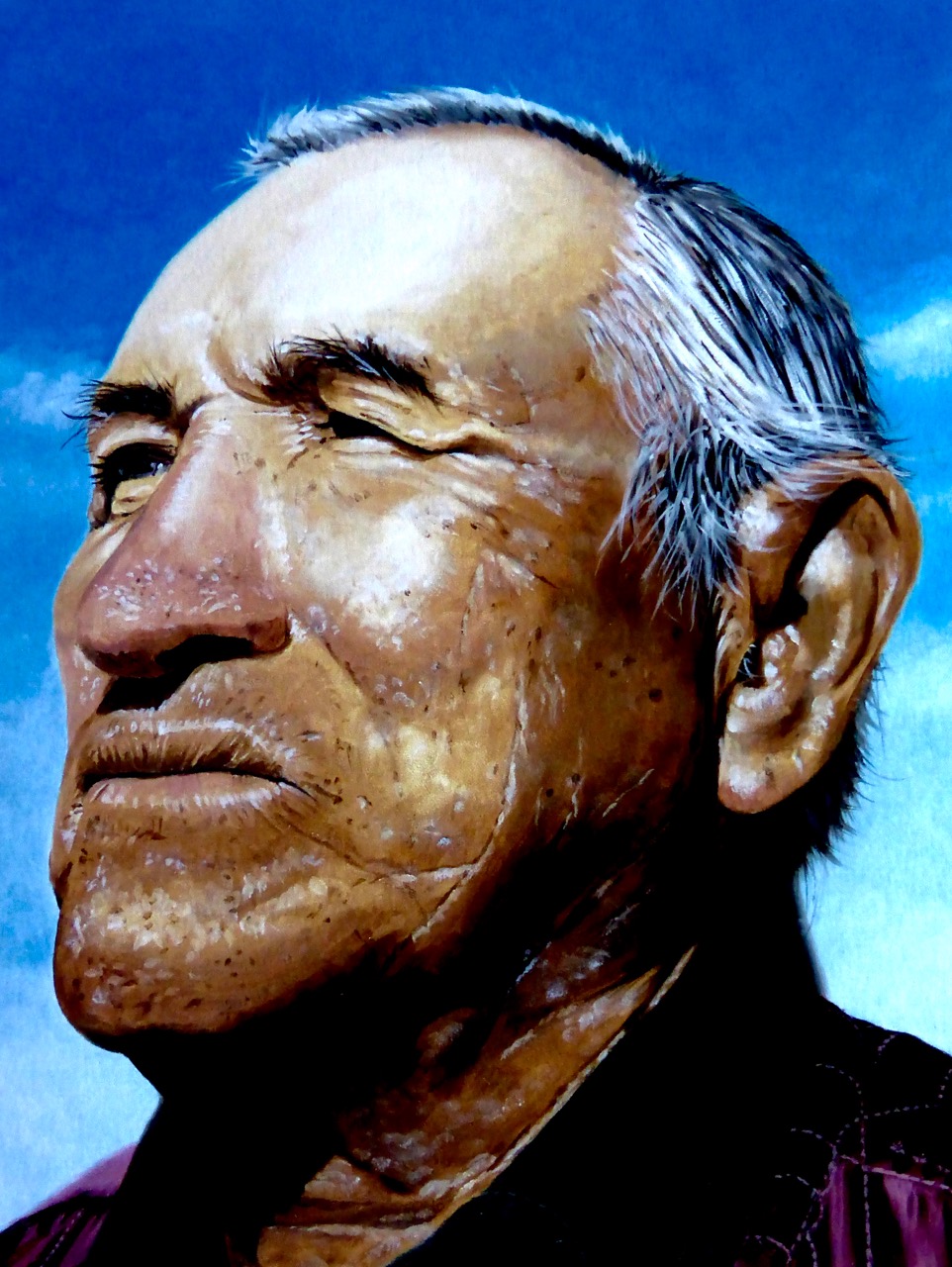

The twenty-fifth of November this year marked the thirtieth anniversary of the passing of my dear friend Lakota Jack Little. Earlier this year I collaborated with internationally renowned artist Denny Karchner from Fort Rickey in the state of Florida on a new painting of Jack to celebrate this special anniversary date. This was the fourth image that Denny has painted from my Native American archived photographs.

The first image to be painted was of Greg Koschtial in 2008 and this was followed by Lakota Jay Eagle in 2010. After a two year break Denny and I decided to paint Cheyenne Danny Reyes from 1992. And now in 2015 we have the painting of Jack Little. Once again Denny has done a amazing job of capturing Jack with his fine line brush strokes.

Jack was born in 1920 and he was one of the last Lakota to be born in a tepee. A medicine man Crazy Cat walked through a snowstorm to give Jack his baby name which was “Hohu.” Jack was from the Rosebud Reservation in western South Dakota although he had family on the Pine Ridge Reservation. As such he says that he is Oglala-Brule-Lakota when addressing people who he meets along the way.

One of Jack’s parental grandfathers Mahalhpapa was a survivor from the massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890. And although he lost a leg in the actions during the battle he walked with a peg leg until his death in 1929. Jack said in his book “Lakota Spirit” that he learned many things from the old plains nomad about how to conduct himself in this earthly life. And it was a sad day when his grandfather passed on into the spirit world.

One of Jack’s relatives, the wife of his grandfathers brother was also a survivor from the Wounded Knee Massacre. In the Lakota way, she was known as “Grandmother” to Jack. Grandmother was a young girl when she was at Wounded Knee and a member of Chief Big Foot’s band. She and her mother were trying to get away from the killing, and her mother was leading a horse. The soldiers killed her mother and the horse, but somehow the bullets missed her, and in the confusion she managed to hide herself between the bodies of her mother and the horse.

She stayed there the rest of the day and all night, and sometime the next afternoon, some of her people from Pine Ridge found her as they were searching the prairie for survivors. Jack said that his grandmother and grandfather Mahalhpaya did not speak ofter of their experiences, but he was sure that just knowing what had happened to them must have had some influence on his feelings even at that young age.

Jack went to mission school and he was given the name “John Baptiste Little.” It was not a happy time for many of the Lakota children who attended these schools. While attending High School Jack played with other Lakota’s from the reservations at basketball. Their team was called the “Sioux Travellers” and for six years they criss-crossed the United States beating all comers on the court. Only on a few occasions did they taste defeat.

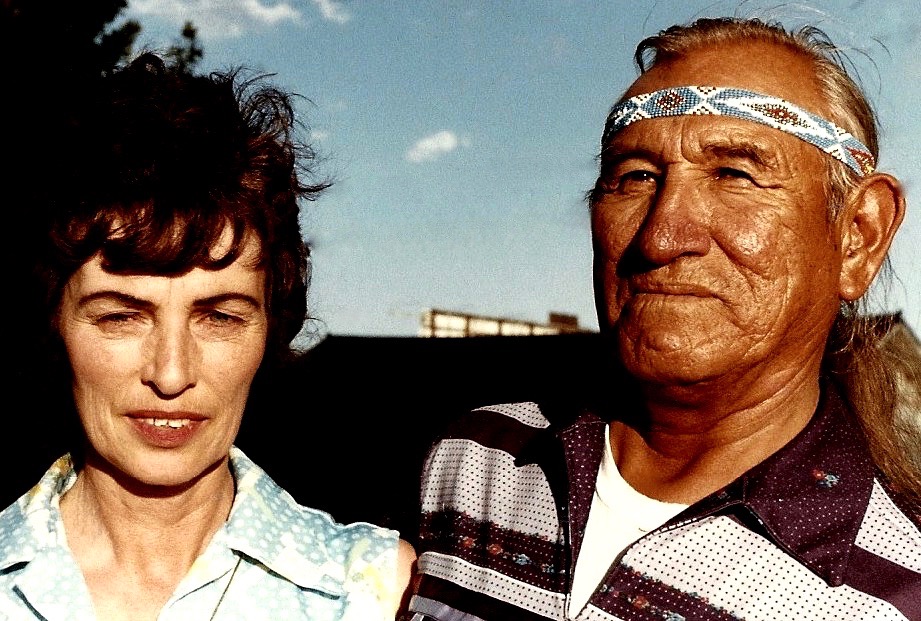

Later he would travel the country performing as a rodeo rider in a Wild West Show. During World War II Jack served in the Merchant Navy. In later life Jack returned back to the Black Hills of South Dakota with his American wife Shirley. Together they worked at the Crazy Horse Memorial until his sudden death in 1985.

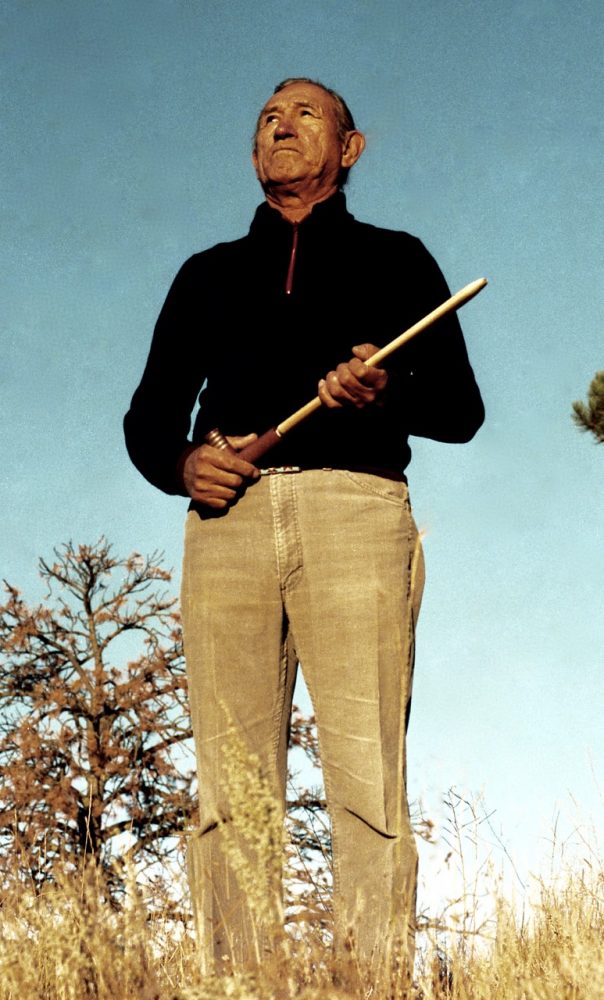

I first met Jack Little and his wife Shirley in late October, 1982 while spending time in the Black Hills of South Dakota. The Black Hills are considered the sacred heart of the Sioux Nation. Jack Little worked as a guide-lecturer at the Indian Museum at Crazy Horse Mountain. Crazy Horse Mountain is a carving in progress of Oglala Sioux War Chief Crazy Horse.

The life of Crazy Horse is symbolic of the Sioux Nation’s fight for freedom and equality. In his capacity as guide/lecturer Jack spoke to a great many people about the Sioux way of life. He was eloquent, direct, informative when talking about his peoples way of life on the Great Plains. Over a number of years as our friendship developed Jack agreed to record his life story with the help of his wife Shirley.

In 1985 I published Jack’s ten thousand word story as a full chapter in my first book “Light at the end of the tunnel.” His story is the personal side, the unconsidered information not included in the history books. And in the summer season of 1992 I published Jack’s story in a thirty-six page booklet titled “Lakota Spirit” The Life of Native American Jack Little 1920-1985.”

Pictured above is the home of Jack and Shirley Little in Custer, South Dakota where I stayed with them both during the summer season of 1985. When Jack passed away in late 1985 she left her job of employment at Crazy Horse Memorial and moved down to Arizona. I always visit the house when I am staying at the home of friends Chuck and Pam Cochran outside Custer. And during my short visits I remember all the fond memories from that time way back in 1985.

When my Powwow: Native American Celebration photographic exhibition was one of only fourteen art forms selected by a panel of museum curators for a three year National Tour of the USA in 1998 I included twenty-five quotations from Jack’s story to accompany the images in the wall text. The images and Jack’s story were exhibited at many prestigious institutions that included the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tennessee, The Sam Noble Museum of Natural History in Oklahoma City, The Sam Houston Memorial Museum in Huntsville, Texas and The Warm Springs Museum in Warm Springs, Oregon.

Later in 2000 I wrote the song “Lakota Spirit” while writing and recording with Sydney musician Chris Fisher the Great Plains musical album as a tribute to the indomitable spirit of the Sioux Nation for Jack and all the Lakota men, women and children who survived the Indian Wars of the late nineteenth century.